NITI Aayog is in the process of finalising the India@2047 vision document, which seeks to set forth the structural changes and reforms necessary to achieve the goal of becoming a $35 trillion developed economy by 2047. The document is anticipated to detail the nation’s strategy for global engagement in trade, investment, technology, capital, and research and development to establish India as a developed country. It underscores the significant role that investment and technology will play in expanding the high-value, high-tech, and skill-intensive manufacturing sectors to increase per capita income. The document’s release is expected within the next few months.

This effort comes amid a worrying backdrop of waning local manufacturing growth and a recent decrease in foreign direct investment inflows into India. Observers are keen to see the recommendations that experts will offer to revitalise India’s manufacturing sector.

READ I Bihar caste survey report highlights deep-rooted poverty

Slowing FDI inflows

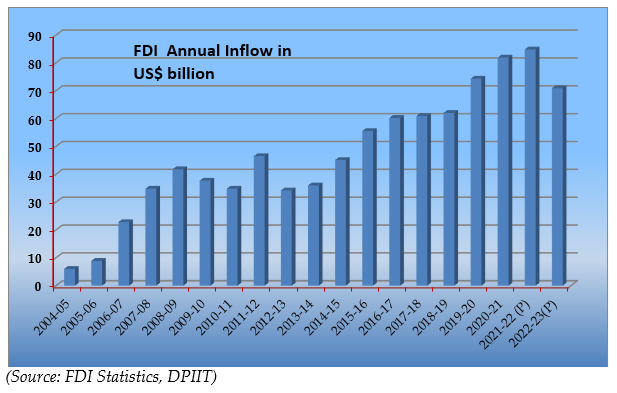

According to data from the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade (DPIIT), FDI equity inflows into India dropped to $10.94 billion in the April-June quarter from $16.58 billion in the same period in the previous year. Furthermore, the Reserve Bank of India’s monthly bulletin reveals a sustained downward trend in the current financial year. Comparatively low FDI equity inflows were reported at $16.63 billion in the first five months of FY 2023-24, down from $26.65 billion and $23.94 billion in the corresponding periods of FY 2022 and FY 2023, respectively. This downtrend is particularly disheartening given the previous expectations to attract $100 billion in FDI in FY 2022-23, highlighting the urgent need to reassess strategies and policies aimed at promoting FDI, especially within the manufacturing sector.

Despite joining the FDI landscape later than other East Asian nations, India’s vast market potential and progressively liberalised policy regime have positioned it as an attractive destination for foreign investors. Since the economic reforms of the 1990s, India has received roughly $ 1 trillion in FDI, contributing to economic growth and a modest increase in per capita income. However, despite considerable GDP growth, India remains classified as a lower-middle-income country, lagging behind Southeast Asian countries in terms of per capita income.

Former RBI Governor C Rangarajan recently addressed India’s economic challenges in becoming a developed economy by 2047, emphasising the low per capita income as a significant hurdle. To overcome this, he pointed out the necessity for the Indian economy to sustain a growth rate of 7% over the next two decades and to increase the Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF) to 32% of GDP from the current 29%. FDI plays a vital role in domestic capital formation, sustaining growth, and reducing poverty, particularly through greenfield investments that create new capital assets and have a more pronounced effect on income and employment generation compared to mergers and acquisitions, which mostly involve the transfer of ownership of existing assets.

Govt support to manufacturing industry

Now let us consider some of the government’s initiatives to promote manufacturing and their impacts:

Make in India: Launched in 2014, this initiative aimed to elevate domestic manufacturing and draw foreign investment, especially in manufacturing. However, the manufacturing sector’s contribution to GDP has not increased as expected.

Ease of doing business: Government efforts, including IT-driven processes and labour law relaxation, have improved India’s EODB ranking. Yet, this has not substantially shifted investor perceptions, and FDI remains concentrated in a few states, indicating uneven business environments across the country.

FDI reforms: The liberalisation of the manufacturing sector for FDI has been extensive, with few remaining policy barriers. Incentives for manufacturing investment could be reconsidered to bolster productivity and demand, particularly in high-tech areas.

Free-trade agreements: India’s stable political climate and large domestic market offer potential advantages from the China Plus One strategy. However, Southeast Asian nations with more FTAs, such as Vietnam, provide stiff competition.

Production-linked incentive scheme: The PLI scheme in 14 key sectors is a strategic move to attract foreign investment and strengthen manufacturing. Its true impact on non-consumer sectors and the development of an ecosystem for components in industries like smartphone manufacturing remains to be seen.

Enhancing product quality: The DPIIT has increased the issuance of Quality Control Orders (QCOs) to boost the quality and brand of Made in India products, supported by the establishment of testing labs and market monitoring.

While these initiatives are steps toward making India a manufacturing powerhouse, challenges such as logistics costs, supply chain issues, labour laws, and land acquisition remain. Continuous review and adaptation of these initiatives, alongside the upcoming vision document, will be critical to India’s ambition of becoming a developed economy by 2047.

Trends and patterns of FDI inflows

Although India entered the race for FDI later than other East Asian nations, including China, its burgeoning middle-class market potential and improved EoDB regime have maintained its appeal as a favourable destination for foreign investors. These strategies have successfully fostered a conducive investment environment. However, to bolster the Indian economy — particularly the manufacturing sector — securing and amplifying foreign investment remains critical. Following a record surge of FDI in the fiscal year 2021-22, there was a subsequent decline of approximately 17%, a downturn linked to global economic challenges.

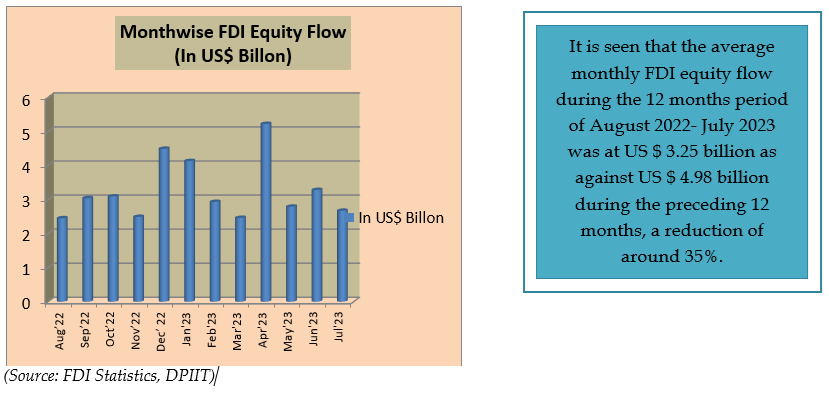

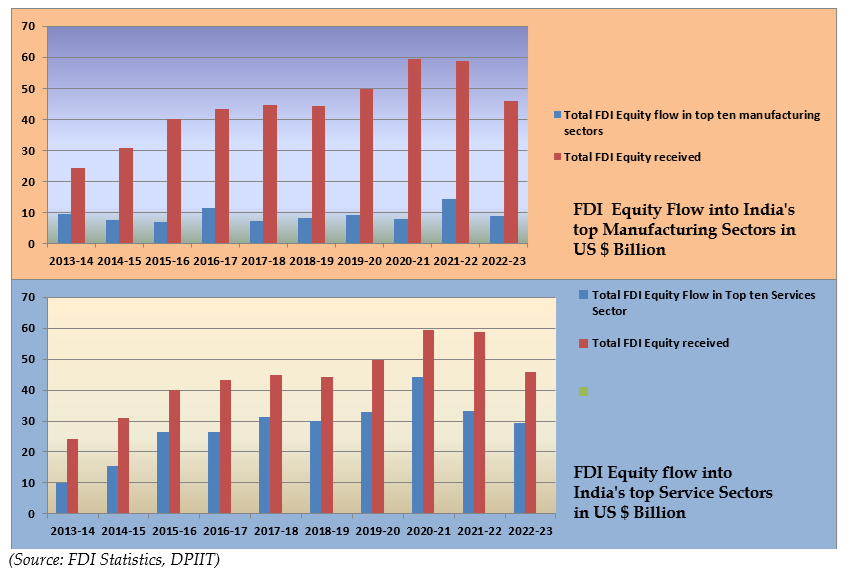

From August 2022 to July 2023, the average monthly FDI equity inflow was $3.25 billion, a stark contrast to the $4.98 billion in the previous 12 months, marking a 35% reduction. Analysing the FDI statistics in individual manufacturing sectors reveals that the leading recipients of foreign investment include the automobile, pharmaceuticals, chemicals, metallurgical industries, food processing, electrical equipment, industrial machinery, cement and gypsum, textiles, and electronics sectors. Investment in these areas has plateaued, fluctuating between $10-11 billion over the past nine years, as the accompanying graph illustrates.

Similarly, an examination of FDI inflows in the top ten services sectors—including IT, trading, telecommunications, infrastructure construction, hospitality, energy, and media—shows that their percentage of the total FDI equity inflow has consistently ranged between 50-70%, in stark contrast to the lesser 20% associated with manufacturing. India’s FDI growth has been buoyed by its skilled, English-speaking workforce, affordable labour, and a vast consumer market of over a billion people, fostering the service sector’s expansion.

The bottom line

Questions arise as to why companies are not as eager to establish manufacturing bases in India. Why have major global automotive companies like Ford and General Motors retreated from the Indian market? Despite ongoing improvements in the ease of doing business, foreign entities continue to grapple with the Indian regulatory landscape, including complexities in taxation, land acquisition, power availability, and cost. Regulatory challenges are not the sole issue. Technological advancement in Indian manufacturing has lagged since the economy opened up in the 1990s.

To enhance the competitiveness of the manufacturing sector and scale up operations, India must tackle barriers to technology development and pinpoint specific areas of focus that address the medium and long-term needs of Indian industry and society. This strategy should involve establishing specialised R&D groups through public-private partnerships. Although India boasts a wealth of scientific human resources, which has attracted many multinational corporations to set up local R&D centres, the lack of structured industry-academia collaboration hampers technological support for the industry. Whether the National Research Foundation (NRF), as envisaged in the New Education Policy 2020, will bridge these gaps remains an important question.

The Indian industry must navigate a rapidly evolving global marketplace with innovation and agility, proactively responding to and capitalising on market trends. Reduced labour costs and production incentives alone will not suffice to transform Indian manufacturers into global frontrunners. A synthesis of data analytics, smart manufacturing, automation, and artificial intelligence is necessary to meet consumer demands, resolve production inefficiencies, manage supply chain disruptions, and leverage new technologies for heightened productivity and efficiency.

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), startups, and micro-enterprises, which dominate the manufacturing sector, particularly need to adopt these technologies to remain cost-competitive. Without combining low-cost labour with smart manufacturing, Indian MSMEs will struggle to gain a substantial competitive edge over their global rivals. Nonetheless, India’s expansive domestic market, especially its growing middle class, provides local manufacturers with significant scale-up opportunities, as seen in China. Moreover, India could learn from China’s success in developing new growth centres beyond its east coast, which initially generated over 60% of their national factory output. This approach could boost FDI inflows, establish new industrial clusters, and mitigate regional disparities.

During a recent visit to India, World Bank President Ajay Banga acknowledged India’s prime opportunity to become a manufacturing supply chain alternative to China. However, he cautioned that India’s window to seize this chance is narrow, ranging from three to five years, not a decade.

The India@2047 vision document is an ambitious manifesto that will chart the path for India to harness its immense potential and rise as a global economic powerhouse. The country stands on the cusp of this monumental milestone, the collective gaze of policymakers, industry leaders, and citizens is fixed on the horizon of possibility. The road ahead will be lined with challenges — a waning manufacturing sector, fluctuating foreign direct investment, and infrastructural bottlenecks — yet the resolve to surmount these obstacles is palpable. The onus is on the nation to transmute this vision into reality, ensuring that the India of 2047 reflects the dreams of its billion-strong populace — a sovereign where prosperity is pervasive, growth is inclusive, and development is sustainable.

Krishna Kumar Sinha is an industrial policy and FDI expert based in New Delhi. His last assignment was as an industrial adviser in the department of industrial policy and promotion, DIPP, currently known as DPIIT, under the ministry of commerce and industry of the government of India.