The recent WTO summit in Abu Dhabi served as a platform for India to voice its concerns regarding the growing trend of protectionist measures under the guise of environmental protection and climate change mitigation measures. Among the hot topics discussed was the European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, which drew attention due to its potential impact on global trade. India’s apprehensions were further compounded by announcements from other key players such as the UK and Japan regarding their own carbon pricing initiatives. These developments set the stage for a deeper analysis of the implications of CBAM and its ramifications for Indian industries and policymakers.

Despite objections over its implications, the reporting period under the CBAM, covering the transition period from October 2023 to December 2025, has commenced. Domestic industries exporting to the EU are now obligated to report their embedded emissions in accordance with CBAM guidelines. However, both the Indian industry and government have raised apprehensions about sharing sensitive and confidential data with customers to comply with EU CBAM reporting requirements. Nonetheless, it appears that CBAM is set to become a permanent fixture.

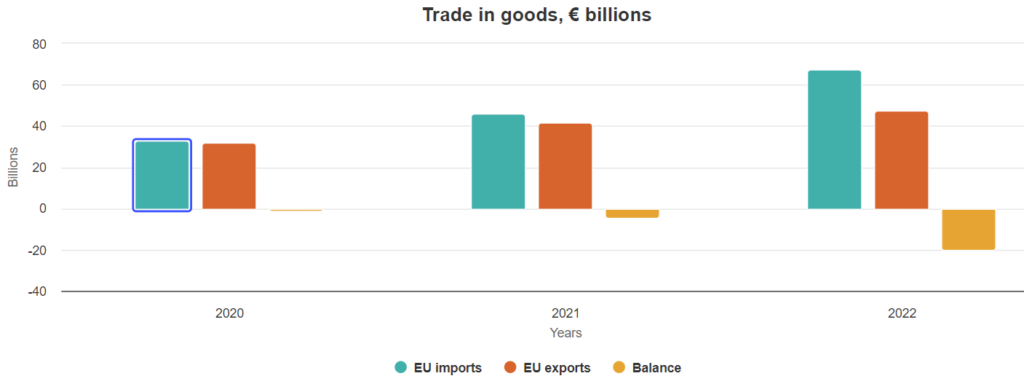

The actual EU carbon levy, scheduled to take effect in January 2026, will apply to six key sectors: cement, iron and steel, aluminium, fertilizers, electricity, and hydrogen. These sectors collectively represent around 12% of India’s exports to the EU, totaling $8.5 billion.

READ I India’s textile industry braces for EU’s aggressive sustainability push

What is CBAM

CBAM is a pivotal component of the EU’s Fit for 55 package, launched in 2021 as part of its green transition programme. The objective is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 55% below 1990 levels by 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2050. CBAM imposes a carbon price on imported products (cement, iron and steel, aluminium, fertilizers, electricity, and hydrogen) entering EU markets based on their embedded carbon emissions. The aim is to prevent carbon leakage, whereby businesses relocate production to countries with less stringent climate regulations to evade stricter norms. These six sectors under CBAM account for 50% of the emissions within the EU Emission Trading Scheme (ETS) sectors.

Currently, the EU’s Emission Trading Scheme operates on a cap-and-trade system, compelling polluters to pay for their greenhouse gas emissions. The revenue generated supports the EU’s green transition efforts. However, to protect energy-intensive industries, the EU initially granted certain industries free emission allowances under the ETS to maintain competitiveness against non-EU producers.

From 2026 onwards, these free allowances will be gradually phased out over an eight-year period until 2034. During this transition, importers will also face a carbon price on their emissions, in addition to the EU’s free emission allowance. This levy will increase as the free allowances are phased out until 2034, leading to a significant rise in carbon costs for EU industries. Importers will also be subject to CBAM during this period.

By instituting a transition period until December 2025 and mandating carbon emission reporting for all importers to the EU, the EU seeks to gather emission data from importers worldwide. This data will help the EU expand or revise the scope of CBAM in the future. Import levies will be calculated based on emissions exceeding the EU’s free allowance, multiplied by the prevailing carbon price in the EU ETS (currently close to $100).

Impact on Indian industry

For India, the greatest impact is expected on aluminium and iron and steel exports, as the EU is a significant destination for these products. Approximately 27% ($2.7 billion) of India’s aluminium and 38% ($3.7 billion) of steel exports are destined for the EU. The levy’s impact is estimated to range from 7-15% ad valorem duty, given CBAM’s current emissions scope. As electricity emissions (Scope 2) are not included in CBAM’s tax calculations, the impact is limited for now. However, if the EU decides to include these emissions post-subsidy phase-out, the impact could be much higher, potentially reaching 25-50%, effectively closing the market for Indian exports to the EU.

Indian aluminium and steel production predominantly relies on coal-fired electricity, resulting in higher carbon emissions per tonne compared with other power sources. Shifting to renewable energy is challenging due to the need for round-the-clock stable power, and alternative sources such as hydro, gas, and nuclear energy face availability constraints in India. Apart from the direct impact, the global trade of coal-fired steel and aluminium exports, which account for over 50% of total global production, will be affected, influencing demand, supply, and prices of these products.

Policy options for India

While India opposes CBAM as an unfair trade practice and challenges it at the WTO, resolution may be prolonged. Alternative strategies are being explored:

Firstly, India is engaging in FTA negotiations with the EU and UK. Despite potential market access gains, CBAM could offset these benefits. Inserting clauses to defer CBAM in bilateral negotiations is being considered to safeguard Indian interests.

Secondly, India is developing its Carbon Credit Trading Scheme, akin to the EU ETS, to consolidate various carbon taxes into a single regime. This “One Nation One Carbon Tax” approach simplifies administration and allows Indian industries to claim adjustments under CBAM or other foreign carbon taxes.

Thirdly, India-EU talks should address the allocation of CBAM funds. Redirecting CBAM proceeds to support green transitions in developing countries aligns with the Paris Agreement’s principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities.”

Lastly, India is contemplating imposing its own carbon tax on exports to the EU, allowing proceeds to fund domestic green initiatives rather than being diverted to the EU. This could serve as a temporary measure until India’s CCTS is established.

The discourse surrounding the CBAM reveals the intersection of trade, climate policy, and economics. India’s concerns highlight the potential impact on its industries, particularly in carbon-intensive sectors like aluminium and steel. To address these challenges effectively, a multipronged approach that includes engaging in free trade negotiations, developing a domestic Carbon Credit Trading Scheme, advocating for fair CBAM proceeds distribution, and exploring options for levying a carbon tax on EU exports. By addressing these issues, India can play a key role in advancing global sustainability goals while safeguarding its own economic interests.

(Prachi Priya is a corporate economist based in Mumbai. Views are personal.)