The government’s flagship pension scheme for unorganised sector workers, the Pradhan Mantri Shram Yogi Maandhan, has experienced low subscriber turnout since its launch in 2019, raising concerns about the viability and effectiveness of PMSYM. Despite India’s unorganised workforce numbering nearly 440 million, as reported by the 2021-22 Economic Survey, the scheme has attracted just over five million subscribers by April 2024.

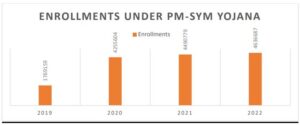

The government’s goal was to enrol 10 million beneficiaries annually starting in the 2020-21 fiscal year. However, the actual enrolment has been significantly lower. In FY20, the scheme added 4.3 million subscribers, but only 0.13 million and 0.16 million joined in FY21 and FY22, respectively. Furthermore, approximately 255,000 individuals dropped out in FY22, weakening the subscriber base. A modest increase occurred in FY24, with 0.6 million new subscriptions.

READ | Refiners’ profits dry up despite cheap Russian crude

PMSYM faces enrolment woes

The scheme’s low uptake is attributed to high inflation and rising living costs, which have made it difficult for unorganised workers to contribute. Its launch coinciding with the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the situation, as many lost their jobs during lockdowns, reducing contributions further.

Despite the government’s efforts, another significant barrier to higher subscription rates is the lack of awareness among potential beneficiaries. Many unorganised workers are not fully informed about the benefits of the PMSYM scheme or the enrolment process. This lack of knowledge is compounded by literacy issues and limited access to digital platforms, which are crucial for registration. Moreover, the complexity of the documentation required can deter many who might otherwise benefit from the scheme. Addressing these informational and procedural hurdles is crucial for expanding the reach and impact of PMSYM.

Subsequent years have not seen improvement. According to labour economist Santosh Mehrotra, incomes in the unorganised sector have remained stagnant while inflation has increased the cost of living.

India’s unorganised sector includes millions of workers, from street vendors to construction workers, who often lack job security and benefits. The pandemic highlighted their vulnerability, as many faced financial hardship due to illness, disability, or old age without a safety net. There is an urgent need to strengthen social security schemes in India to mitigate such risks. Providing a guaranteed pension upon retirement or disability would offer security and dignity to vulnerable societal segments.

What is PMSYM

PMSYM is a voluntary pension scheme that provides old-age protection. Workers aged 18 to 40 contribute between Rs 55 and Rs 200 monthly, matched by the government. Upon reaching 60, they are eligible for a minimum guaranteed pension of Rs 3,000 per month. The scheme also includes a family pension benefit in the event of the beneficiary’s death. Eligibility is limited to unorganised workers earning less than Rs 15,000 per month, who are not in the organised sector or income tax payers.

In FY20-21, the government allocated Rs 500 crore to the scheme, spending about Rs 319.71 crore. The allocation was reduced in the following years, with Rs 350 crore allocated in FY22-23 and expenditures of approximately Rs 193 crore by March 1, 2023. As of December 31, 2022, 20,70,704 males and 23,47,809 females had registered under PM-SYM. The Life Insurance Corporation (LIC) of India manages the fund.

Lack of awareness deter enrolment

With ambitions to enrol 100 million workers within five years, the scheme aims to become one of the world’s largest pension plans. However, given its low subscription, the Labour Ministry has informed the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Labour that the scheme is under evaluation by the Indian Institute of Public Administration (IIPA) to improve its reach and effectiveness.

To improve the uptake of the PMSYM scheme, the government could consider implementing targeted awareness campaigns and simplifying the enrolment process. Collaborating with local NGOs and community leaders could help in disseminating information effectively, particularly in rural and remote areas. Additionally, setting up dedicated helpdesks to assist with registration and resolve queries could alleviate procedural complexities. Leveraging mobile technology to facilitate easier registration and payment could also make the scheme more accessible to a broader audience.

Acknowledging these challenges is a positive step. Moving forward, policymakers should consider expanding beyond PMSYM to develop a comprehensive social security framework that includes unemployment benefits, healthcare access, and maternity leave provisions. Without such support, India’s aspirations to become a developed nation will remain unfulfilled.