The Economic Survey’s recommendation to open the doors for Chinese Foreign Direct Investment into India raises significant concerns that must not be overlooked. While the Economic Survey posits that Chinese FDI inflows could enhance India’s economic growth, employment, and technological capabilities, a more nuanced approach grounded in long-term pragmatism and national security is needed.

The eagerness to open up the economy to Chinese investments must be tempered with national security considerations. Instances where Chinese investments have raised concerns about data breaches and unauthorised access to critical information highlight the potential risks. For example, the involvement of Chinese investments in India’s payment sector led to regulatory intervention due to concerns about potential breaches of consumer data and unauthorised access to information.

While these are market speculations at best, such issues could remain hidden due to strict regulations and financial sector supervision. However, if proven true, they pose significant regulatory and political challenges. It is essential to learn from these examples and recognise the vulnerability of national systems—such as financial services, healthcare, and strategic assets like power sectors and computing—to international investments, whether in the form of capital or debt.

READ I Digging deeper: India’s critical minerals quest

Chinese FDI and strategic autonomy

Historical precedents suggest that the allure of cheap Chinese technology and investments could lead to dependencies that undermine India’s strategic autonomy. For instance, while India imports components for solar panels from China, it remains dependent on skilled Chinese talent for their installation. Any decision to welcome Chinese FDI must, therefore, be made with a thorough assessment of potential vulnerabilities and long-term implications for national security.

India must balance its economic interests with strategic autonomy. The perception that Chinese technology is more affordable than Western alternatives should not overshadow the potential long-term costs and vulnerabilities. India’s participation in initiatives like the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) and the Supply Chain Resilience Initiative (SCRI) underscores the importance of diversifying supply chains and reducing dependency on China. Embracing Chinese FDI could undermine these efforts, exposing India to greater risks and dependencies.

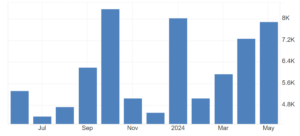

Foreign direct investment inflows into India ($ million)

Proponents of increased Chinese FDI often cite the experiences of countries like Vietnam and Singapore, which have successfully attracted Chinese investments while maintaining technological diversity. However, India’s unique geopolitical context necessitates a more cautious approach. Unlike Vietnam and Singapore, India has a complex and contentious relationship with China, marked by historical tensions and ongoing border disputes. The strategic imperative for India is to ensure that foreign investments do not compromise its sovereignty or economic security.

China is already India’s largest import supplier across multiple industrial categories. Allowing Chinese firms to ‘Make in India’ could overwhelm domestic industries, leading to the closure of many Indian businesses unable to compete with Chinese companies. This shift could transform India from a global manufacturing aspirant into a trading nation, heavily dependent on Chinese firms for critical supplies and economic growth. Such dependence would undermine India’s long-term economic security and strategic autonomy, creating vulnerabilities in key sectors and diminishing the nation’s capacity to sustain and grow its industrial base independently.

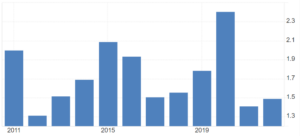

FDI inflows into India as percentage of GDP

While it is true that India must learn to work with major powers and global manufacturing hubs like China, it is essential to consider long-term strategy and reliability. India should carefully weigh the costs and potential vulnerabilities of adopting Chinese technologies, which may appear cheaper than Western alternatives.

The nation must assess the risks involved and plan accordingly, ensuring scalability and efficiency in any alternative models. Aligning with national or regional powers that India currently feels comfortable with is acceptable, but over time, the country should be prepared to shift to technologies that best serve its national interests. Any comparison to other nations partnering with China for technology must be viewed through a national security lens, not just from a trade perspective.

In navigating its economic relationship with China, India must uphold its democratic values and ensure inclusive growth. This requires the government to play a pivotal role in shaping economic activity that supports not just conglomerates but also small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Lessons can be learned from China’s development of its SME sector, which has significantly contributed to its GDP growth since the late 1980s. The focus should be on fostering an environment where domestic industries can thrive and contribute to the nation’s economic growth and technological advancement.

Before making any decisions, India must realistically assess the extent to which it can tolerate any possible friction arising from Chinese FDI and how to fend off geopolitical challenges or economic pressures. Despite all postures, Chinese dogmatic bullheadedness in stalling India’s global efforts is well known—be it at the UN, blocking terrorist tags for those who attacked Indian soil, or border intrusions into Indian territory.

If Indian markets and businesses require Chinese skill and technology, they must collaborate with caution to ensure that Indian business systems are not infiltrated by long-term Chinese moles. This is the larger context that businesses often miss. While the technological and economic benefits of such collaborations are clear, the potential risks to national security and economic sovereignty are significant. Ensuring that collaborations are tightly regulated at entry-level and monitored at regular intervals, including random assessments, is essential to protect India’s interests and maintain control over critical sectors.

A balanced approach, focusing on diversifying supply chains, fostering domestic industries, and upholding democratic values, is crucial for sustainable growth.

While nationalistic pride might make us feel we do not need any other nation, especially competing and intrusive players like China, the reality of how interlinked global supply chains are with China tells a different story. Assuming that Western nations are “safe” and “friendly” overlooks the dangers of data and digital bondage tied to global tech entities, especially those owned and regulated by the West. Furthermore, it would be a policy folly to believe we can “control” any Chinese investments or presence in India. Capital has a way of influencing business behavior, and regulations can only enforce a limited set of ethical and governance norms.

This Economic Survey’s idea seems like a test balloon that probably checks reactions from different stakeholders. As India seeks to become a global manufacturing hub, policies must navigate the delicate balance between economic nationalism and globalisation to ensure that the nation’s strategic interests are safeguarded. Short-term economic gains from Chinese investments must not blind us to the long-term vulnerabilities they introduce. Protecting our strategic autonomy and national security demands a cautious and balanced approach to foreign direct investment.

Srinath Sridharan is a strategic counsel with 25 years experience with leading corporates across diverse sectors including automobiles, e-commerce, advertising and financial services. He understands and ideates on intersection of finance, digital, contextual-finance, consumer, mobility, Urban transformation, and ESG. Actively engaged across growth policy conversations and public policy issues.