Women have ascended to positions of power around the world, and we are witnessing a moment in history where merit and talent seem to take precedence over prejudice and tradition. This shift is opening doors for all genders to reach their full potential, free from societal constraints. India is a notable example, having had a female Prime Minister just two decades after independence and, subsequently, two female Presidents. While long-standing barriers that historically limited women have been broken, and glass ceilings shattered, this is only part of the story. A more subtle form of bias — what could be called benevolent glass ceiling — still persists in modern society.

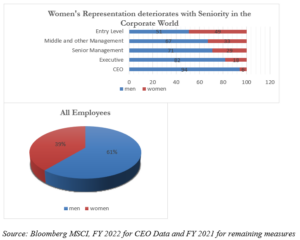

These barriers, disguised as protection, kindness, or concern for perceived limitations, continue to hold women back from advancing in their careers or attaining leadership roles. Despite progress, many challenges remain in the 21st century that hinder women’s growth. As one moves up the hierarchy, the benevolent glass ceiling becomes more pronounced. Higher-level positions are often dominated by entrenched networks resistant to change. With fewer available top positions, competition increases, making it harder for underrepresented genders to break through. This results in a concentration of power that tends to exclude those outside the dominant group. Data from Bloomberg and MSCI on the decline of female representation in senior corporate roles is particularly alarming.

READ I The mall effect: Consumerism widens inequality in India

Glass ceiling in legal profession

This situation extends to the judiciary as well. Despite more women entering the legal profession, they remain underrepresented in higher judicial positions. In many countries, the percentage of female judges declines as the judicial hierarchy ascends. The Indian judiciary is no different; the problem of poor representation remains unaddressed.

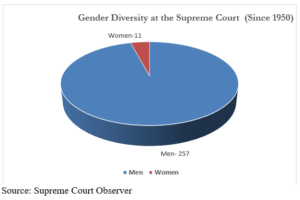

The current Chief Justice of India has acknowledged the significant proportion of female recruits in the judiciary but expressed concern over the inadequate representation of women in higher judicial positions. With the judiciary evolving from an adjudicating organ to a welfare policy promoter, diversity has become essential for the effective institutionalisation of the justice system. In India, the Supreme Court currently has only 3 women out of 34 judges, less than 9%. In a profession like law, women must hold equivalent positions to ensure democratic legitimacy, give voice to historically marginalised sections of society, and reflect their proportion in both the general population and among law graduates.

Since the establishment of the Supreme Court in 1950, only 11 women have served as judges out of a total of 268, and to date, there has not been a female Chief Justice. This lack of representation is reflected in the High Courts as well, where just 83 of the 680 judges are women. It took almost four decades after the creation of the Supreme Court for the first female judge, Justice Fathima Beevi, to be appointed in 1989. Although Justice B.V. Nagarathna is expected to become India’s first female Chief Justice in 2027, her tenure will last only 36 days if the current system of appointing the senior-most judge as Chief Justice is followed.

The root causes of this underrepresentation — whether patriarchal structures, an opaque collegium system, or flawed policies — remain unclear. Justice Gyan Sudha Misra once remarked that disbelief in the abilities of women is still deeply rooted in society, which prefers token female representation in the judiciary rather than equal participation. Similarly, Indira Jaising noted that alive and kicking patriarchy prevents women from breaking the glass ceiling, with the entrenched old boys’ club mentality making it harder for women to secure judicial appointments. This underrepresentation, combined with symbolic participation and the constant need to prove one’s worth, perpetuates a self-sustaining patriarchy and male-dominated leadership that exacerbates gender inequalities.

A particularly troubling bias is the conflation of aggression with competence. Zealous lawyering is often seen as synonymous with courtroom success, leading clients to prefer assertive male attorneys. This bias, perpetuated by the media and societal norms, casts female judges’ natural communication styles—such as empathetic listening and collaboration—as weaknesses. In reality, these approaches foster respect and a calm atmosphere conducive to conflict resolution. Yet women in the legal profession often feel pressured to match the loud, aggressive behavior of their male counterparts, which can undermine their confidence and well-being.

This pervasive bias toward “aggressive” male lawyer archetypes also fosters a “fear of failure” in women. Female lawyers face a brutal double bind: they must either project aggression, reinforcing harmful stereotypes, or display compassion, risking being seen as incompetent. Constantly negotiating these expectations can erode their confidence, compromising their authenticity and mental health. This dynamic often leads to imposter syndrome, self-doubt, and increased pressure, all of which affect their performance and career progression.

Conversely, men who exhibit loud and intimidating behavior are not only normalised but often praised as confident and competent. This bias, compounded by the adversarial nature of the legal profession, creates a challenging environment for women and reinforces the dominance of the “old boys’ club.” The judiciary has long been associated with men in black robes, and when women entered the field, they had to conform to male standards. Little attention has been paid to the unique contributions women could make if the legal profession were truly gender-neutral. Cultural stereotypes continue to suggest that women lack “what it takes” to succeed in law.

The author strongly believes that better representation of women in the judiciary is essential to improve and balance the justice delivery system. Women bring diverse life experiences and perspectives that enhance fairness, impartiality, and decision-making. Having women in judicial leadership roles not only signals that the courts are open and accessible to all but also encourages younger women to pursue legal careers. By breaking both the vertical glass ceiling and the lateral glass wall, we can ensure a more diverse and just judiciary.

To achieve this, we must engage in transparent conversations about race and gender, challenge unconscious biases, and celebrate the successes of women for their skills and worth, not out of misguided benevolence. Breaking gender stereotypes is crucial because a diverse judiciary is fundamental to fairness and equality, inspiring public confidence in the justice system and encouraging more women to enter the legal profession. Together, we must be the change we want to see.

(Dr. Manisha Mirdha is Associate Professor and Dean Student Welfare, Humanities and Social Sciences, NLUJ.)