India’s aspiration to become a developed country by 2047, as articulated by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, is a bold and inspiring vision. The year marks the centenary of India’s independence, symbolising a desire to elevate the nation’s status on the global stage. However, the road to this goal is fraught with challenges. While India’s macroeconomic fundamentals are strong, critical structural weaknesses—particularly the fragile state of public finances at the state level—threaten to impede the country’s development journey.

Achieving the vision of Viksit Bharat will require the country to address systemic financial imbalances, governance inefficiencies, and a looming middle-income trap that could affect its growth trajectory. The biggest stumbling block on the path of India becoming a truly developed economy would be weak state government finances that have the potential to derail India’s growth momentum.

READ | Risk and growth: Banks need to exercise caution amid global turmoil

Overcoming middle-income trap

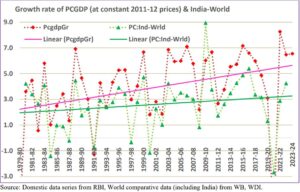

India’s dream of breaking into the ranks of high-income nations is not guaranteed, World Bank Chief Economist Indermit Gill said in a recent interview. Gill warned of the risk of India falling into the middle-income trap, a scenario where countries struggle to advance beyond a certain income level, typically around $4,000 to $7,000 per capita. India, with a current per capita income of roughly $2,500, must tread carefully to avoid stagnation in this income range.

Real Per capita GDP (PCGDP) growth (%): Domestic and relative to World growth

Gill’s views are backed by sobering statistics: since 1990, only 34 countries have transitioned from middle-income to high-income status, and none of these nations were as populous or as complex as India. Many of the countries that succeeded were either resource-rich, such as those benefiting from oil booms, or were geographically proximate to high-income markets such as the European Union. Indiadoes not have these advantages. Its success, therefore, will hinge on its ability to implement structural reforms that boost productivity, enhance economic freedom, and create equal opportunities for women — key elements Gill identifies as necessary for escaping the middle-income trap.

Indian states key to Viksit Bharat

India’s growth targets, set out in the NITI Aayog’s Viksit Bharat vision, are nothing short of ambitious. To become a developed economy by 2047, India must grow at a sustained rate of 7-10% annually over the next two to three decades. By 2047, the government envisions India as a $30 trillion economy with a per capita income of $18,000. However, these targets will remain aspirational unless India addresses the foundational weaknesses in its economic framework.

Key among these weaknesses is weak state government finances. The role of state governments in driving economic growth in India cannot be overstated. As India’s federal structure places considerable responsibility on the states for delivering essential public services — ranging from education and healthcare to infrastructure development and law enforcement — their performance is intrinsically linked to the country’s economic trajectory. States are the primary actors in shaping the business environment, managing land and labour reforms, and ensuring efficient public service delivery, all of which are crucial for fostering sustainable growth.

Without effective governance at the state level, even the most well-intentioned national policies can falter. Moreover, the diverse economic, social, and cultural realities of India’s regions necessitate tailored approaches that only state governments, with their proximity to local issues, are capable of implementing effectively. In this context, state-led reforms in public finance management, infrastructure investment, and human capital development become the linchpin of India’s ambitions to not only accelerate growth but also to ensure that it is inclusive, lifting millions out of poverty and bridging regional disparities.

The state governments are not merely administrative units but essential drivers of India’s economic future, and their financial health and governance capabilities will determine the nation’s success in achieving its development goals. Yet, they are mired in deficits, mounting debt, and inefficient spending, all of which jeopardise the country’s long-term growth prospects.

Fragile state finances

India’s state governments face a fiscal crisis that is becoming progressively more precarious. Many states are grappling with rising deficits and unsustainable debt burdens. The uncertainties around GST compensation, which is a crucial revenue source for states, has exacerbated their financial woes. States like Punjab, Himachal Pradesh, and West Bengal now face significant revenue shortfalls, compelling them to resort to increased borrowing, thereby worsening their debt profiles.

This fiscal stress is compounded by rising expenditure commitments, particularly in the form of subsidies. Many states have adopted policies that, while politically advantageous, are fiscally unsound. In Punjab, Rajasthan, and Andhra Pradesh, for example, a significant portion of state budgets is allocated to subsidising electricity and agricultural inputs. These politically motivated handouts, while offering short-term relief to constituents, are draining resources that could otherwise be invested in infrastructure, education, and health — key pillars of long-term economic growth.

For India to achieve sustained, high growth rates, significant investments in infrastructure are essential. Infrastructure development not only boosts productivity but also improves access to markets, lowers transaction costs, and enhances the overall business environment. Yet, many state governments are curtailing their capital expenditures, constrained by limited fiscal space.

The inclusion of off-budget borrowings in the fiscal responsibility targets has further squeezed the borrowing capacity of states, reducing their ability to invest in critical infrastructure projects. This reduction in capital expenditure is particularly alarming given that infrastructure investment is crucial for sustaining long-term growth. In states like Kerala and West Bengal, high debt-to-GSDP ratios have eroded the ability to finance new projects, threatening to stall growth in these regions.

Sustainability of debt

Many states are at risk of breaching their fiscal responsibility targets, a situation that could lead to a debt sustainability crisis. States like Kerala and West Bengal, which have high debt-to-GSDP ratios, are particularly vulnerable. The growing burden of interest payments is consuming an increasing share of state revenues, leaving less room for productive investments.

Without immediate corrective measures, such as tighter fiscal controls and improved resource mobilisation, these states may struggle to maintain essential services and development programmes. The current fiscal trajectory risks not only undermining the growth potential of individual states but also the national economy as a whole.

Need for structural reforms

To restore fiscal stability, states must undertake structural reforms that go beyond cosmetic fixes. Rationalising GST rates, expanding the tax base, and improving the efficiency of public spending are critical steps. States need to streamline their subsidy programmes, ensuring that subsidies are better targeted and fiscally sustainable. Discom reforms must be accelerated to reduce the financial stress on power distribution companies, which in turn would alleviate some of the fiscal pressures on state budgets.

Public financial management reforms are essential to enhance fiscal discipline. States should adopt more rigorous monitoring of contingent liabilities and explore innovative revenue-generation avenues, such as land monetisation and public-private partnerships (PPPs), to bridge funding gaps.

A case for decentralised growth

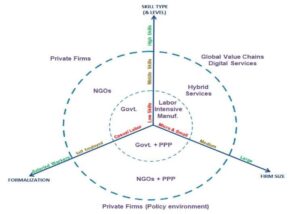

India’s diversity demands a decentralised approach to development. States must be empowered to tailor their economic strategies to their unique circumstances. The effectiveness of governance starts with localised service delivery. States that prioritise governance reforms—such as reducing leakage in welfare programmes, improving data quality, and adopting technology-driven solutions—can significantly enhance the impact of public spending.

The model of decentralised governance has worked well in countries like China, where local governments have been granted significant autonomy to drive development. In India, however, only 3% of government spending occurs at the local level, compared with 50% in China. Increasing fiscal decentralisation would allow states to align their fiscal policies with their development priorities, ensuring that public funds are spent efficiently and in areas that offer high social returns.

Developing human capital

Investment in human capital is critical to India’s long-term economic success. Yet, despite substantial public spending, India’s human capital outcomes remain poor. In education, a significant portion of children in rural areas complete primary school without basic literacy skills. In health, 35% of children are stunted, impairing their long-term cognitive and economic potential.

Job skilling is a 3-Dimensional problem

States must prioritise investments in early childhood education, public health, and nutrition, as these sectors offer some of the highest returns on investment. Programmes that have shown success, such as performance-linked pay for public sector employees or technology-driven interventions to reduce leakages in welfare programmes, should be scaled up to ensure that public funds are spent efficiently.

India’s aspiration to become a developed country by 2047 is achievable, but only if it addresses the structural weaknesses in its economy—chief among them the fragile financial position of state governments. States are responsible for delivering critical public goods, must strengthen their fiscal positions through structural reforms, better resource mobilisation, and improved public financial management.

The decentralisation of economic governance, coupled with a renewed focus on human capital investment, offers a promising path forward. If India can strengthen its governance systems and ensure that public funds are spent efficiently, it will be well-positioned to escape the middle-income trap and achieve its vision of becoming a developed country by 2047. However, without these reforms, the dream of a developed India risks remaining just that — a dream.

Anil Nair is Founder and Editor, Policy Circle.