Kerala economy facing fiscal distress: The Kerala model of development has garnered significant academic attention over the years. The state has achieved commendable outcomes in healthcare and education — high Human Development Index rankings, low infant mortality rates, and increased life expectancy. However, a closer look at Kerala’s economic performance reveals a paradox: while it excels in social indicators, the state faces significant economic and fiscal challenges, particularly as it struggles to sustain industrial growth and manage mounting fiscal stress.

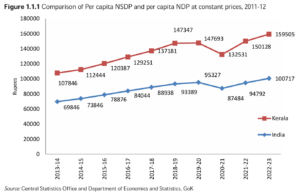

Kerala’s economy, with a projected gross state domestic product (GSDP) of Rs 13.11 lakh crore for the fiscal year 2024-25, ranks 11th among Indian states. The state’s per capita GSDP stands at Rs 2,95,787 for 2022-23, compared with the national average of Rs 1,96,983. This positions Kerala among India’s richest states like Karnataka (Rs 3,32,926) and Tamil Nadu (Rs 3,15,220).

Kerala has consistently ranked among India’s top states in terms of social indicators, leading in areas such as literacy, life expectancy, and social security. According to recent data, the state has the lowest multidimensional poverty rate in India, at around 14.9%, compared with the national average of 24%. Kerala also ranks highly in digital infrastructure, with an advanced internet penetration rate and high telephone density. This strong foundation has empowered various social segments through initiatives that reach a substantial proportion of the population.

In terms of multidimensional poverty, Kerala has achieved remarkable success. According to NITI Aayog’s Multidimensional Poverty Index 2023, the state has the lowest poverty rate in India at 0.76%, significantly below the national average of 11.28%. This achievement highlights Kerala’s effective social policies and commitment to improving living standards for its residents.

READ I Middle class crisis: Quality of life takes a hit as incomes erode

Industrial and agricultural decline

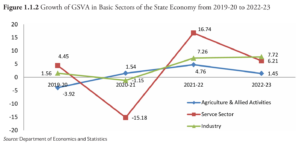

Despite these social gains, Kerala’s economic structure reveals deep-seated challenges. While the state experienced rapid growth in the service sector, agriculture and industry have lagged. Agriculture’s share in the state’s economy has shrunk drastically, falling from 29% in 1991 to just above 10% in recent years. This decline is partly attributed to the structural transformation observed in developing economies, where agriculture typically plays a decreasing role over time. However, in Kerala’s case, industrial development has not filled this void. Instead, the state is experiencing rapid deindustrialisation, adding to its economic stagnation.

The service sector has nearly doubled its share in the state’s gross state domestic product (GSDP) over the past few decades, but this growth alone cannot offset the slowdown in other sectors. The manufacturing sector, in particular, has not realised its potential, leading to one of the highest rates of deindustrialisation in the country. This lack of balanced growth across sectors presents a critical challenge, especially in providing adequate employment opportunities.

Fiscal challenges of Kerala economy

Kerala is widely regarded as one of India’s most fiscally stressed states. High debt, limited revenue sources, and constraints on fiscal autonomy have strained its financial health. Kerala’s fiscal stress has compelled the state government to seek interventions from the Supreme Court, arguing that it has been denied constitutionally guaranteed entitlements. Despite Kerala’s efforts to increase revenue, including enhancing tax revenue as a percentage of GSDP, the state remains heavily reliant on central transfers and grants, leaving limited room for fiscal manoeuvre.

Kerala’s debt-to-GSDP ratio, currently around 35%, is well above the national average of 25%. This high debt burden limits the state’s capacity for developmental expenditure, further straining the already limited fiscal space. The state’s high committed expenditure on social programs and public sector wages adds to its fiscal strain, presenting a unique challenge for sustainable fiscal management.

Finance commission and federal fiscal relations

The Finance Commission plays a crucial role in shaping fiscal federal relations in India by determining how revenue is shared between the Union government and states. However, Kerala argues that the existing framework does not adequately account for the state’s unique characteristics and developmental needs. The Finance Commission’s devolution formula, which includes criteria such as income distance, population, and area, tends to penalise states with high human development indicators, like Kerala, which may collect less tax revenue due to its focus on human capital production.

The centralisation of certain tax revenues through the Goods and Services Tax (GST) has further exacerbated this issue. Kerala, as a consumer state, anticipated substantial gains from GST but has not seen the expected revenue growth. The state’s revenue from GST remains lower than anticipated due to the limitations in capturing value-added tax from its service-driven economy. This is a critical issue, as Kerala relies heavily on service exports and remittances, both of which contribute less to GST collections.

A paradigm of human capital production

Kerala’s economy is fundamentally different from that of manufacturing-oriented states. Rather than relying on tangible goods production, Kerala has specialised in exporting human capital, particularly skilled workers in healthcare and education sectors, across India and internationally. This model has brought significant remittance inflows, accounting for 23% of India’s total remittances, benefiting both Kerala’s economy and the national exchequer. However, while this human capital export has enriched the population and supported the state’s social achievements, it has not translated into substantial tax revenue for the Kerala government, leaving it financially strained.

This reliance on human capital export highlights the paradox of Kerala’s economic model: while the people of Kerala are relatively prosperous due to high remittance inflows, the state government struggles financially. Unlike states that produce and export goods, Kerala cannot collect taxes on the exported labour, further limiting its fiscal resources.

To address Kerala’s unique fiscal challenges, there is a pressing need for the Finance Commission to revisit its devolution criteria. The current formula tends to disadvantage states with service-oriented economies that rely on human capital exports rather than tangible goods. Adjusting the devolution formula to account for the contributions of human capital to national development could provide Kerala with much-needed fiscal space.

The upcoming 16th Finance Commission has the opportunity to address these imbalances. Ensuring that states like Kerala receive a fair share of revenue based on their unique contributions to national growth, especially through remittances, would enable the state to invest more effectively in its developmental goals.

Kerala’s model of development has highlighted the potential for states to prioritise social welfare while facing economic challenges. However, for Kerala to continue leading in social indicators while ensuring sustainable economic growth, a reimagined approach is required. By addressing fiscal imbalances, enhancing revenue-raising mechanisms, and supporting industrial and agricultural growth, Kerala can work towards a more resilient and sustainable economic future. The state’s focus on human capital has brought immense value to its people, and with better fiscal support, Kerala can continue to thrive and set an example for inclusive growth in India.