While learning outcomes in primary schools have improved post-pandemic, enrolment in government schools has declined to pre-pandemic levels. According to the Annual Status of Education Report 2024 (ASER 2024), private school enrolment has increased, though the reasons for this shift remain unclear. Despite the enrolment decline, reading and arithmetic skills have improved, in some cases even surpassing pre-pandemic levels

The ASER 2024, curated by the non-governmental organisation Pratham, provides critical insights into learning gaps in Indian schools. The latest report, released last week, presents a mixed picture—while significant challenges remain, there are notable improvements. The pandemic-induced learning loss has largely been mitigated, marking a reversal of the setbacks caused by prolonged school closures.

READ | Repo rate cut: Decoding RBI’s first rate cut in five years

There has been substantial improvement in pre-primary education, with enrolment figures showing a steady increase. Another key highlight is the relatively high degree of digital awareness among children aged 14-16, though most of them use smartphones primarily for social media rather than for educational purposes.

ASER 2024 reveals gains across states

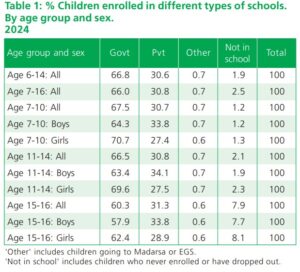

Even traditionally low-performing states such as Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Madhya Pradesh have shown improvements compared with 2022. The survey, conducted across 6.4 lakh children in nearly 18,000 rural villages, highlights an overall positive trend in foundational learning. Despite the drop in government school enrolment to 66.8% in 2024—down from the pandemic peak of 72.9% in 2022 and close to the 2018 figure of 65.6%—learning outcomes have improved. For instance, the percentage of Class 3 students who can fluently read Class 2-level text has risen to 27.1%, up from a pandemic low of 20.5% and even surpassing the 2018 level of 27.3%.

The report emphasises that the right to education mandate for universal enrolment of children aged 6-14 is nearly achieved. However, about 1.9% of children in this age group remain out of school, a slight increase from 1.6% in 2022. India experienced some of the longest school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic, significantly disrupting education. The shift to digital learning left many underprivileged students behind, as online classes could not replicate the in-person classroom experience. The pandemic widened the gap between grade level and actual learning, making the need for remedial action more pressing than ever.

The National Education Policy (NEP) has played a crucial role in addressing foundational literacy and numeracy, helping to reverse pandemic-induced setbacks. The report notes that states have adopted NEP’s recommendations in various ways, but all have embraced the policy’s teacher-centric approach. Unlike previous education programs, which had limited national coordination, the current effort appears to be more sustained and results-oriented.

Schools have been directed to implement targeted interventions, and teachers have undergone specialised training. Pre-primary enrolment has also surged, rising from 68.1% in 2018 to 77.4% in 2024, largely due to Anganwadi centres. This increase is a promising development, as early childhood education not only prepares children for formal schooling but also supports broader developmental outcomes, such as immunisation and nutrition.

Digital literacy: A double-edged sword

For the first time, ASER 2024 assessed digital literacy among children aged 14-16. Around 90% of respondents reported having access to a smartphone at home, and over 80% stated they knew how to use one. Encouragingly, awareness of online safety measures was also relatively high. However, most children use smartphones for social media rather than educational activities. Kerala stood out, with over 80% of surveyed children using smartphones for education and over 90% for social media. With technology playing an increasingly dominant role in education, the high penetration of smartphones presents an opportunity to integrate digital learning into school curricula. However, ensuring that digital resources are used effectively remains a challenge.

The Indian education system has evolved significantly in recent years, reflecting the demands of a digital era. However, despite the positive trends in the latest survey, policymakers and stakeholders must not become complacent. Significant gaps remain, particularly in rural areas, where policy benefits are often the last to reach. Over 50% of Standard V children still cannot read Standard II-level text, highlighting the need for urgent intervention. A key takeaway from ASER 2024 is that teacher training alone is not enough—continued post-training support is essential to bridge the gap between syllabus completion and effective learning.

More than 100 million children are currently in the foundational learning stage. By the time they graduate from school, India will be at a crucial juncture in realising its demographic dividend. This window of opportunity will remain open for at most another decade and a half. Policymakers must read the ASER 2024 report in its entirety and focus on the areas that require immediate attention. The need for quality education cannot be overstated in today’s economic landscape.

No investment in the education sector is excessive, given that India’s long-term prosperity hinges on its ability to equip its youth with strong foundational skills. The findings of ASER 2024 should serve as both a marker of progress and a reminder that much remains to be done.