In public discourse, the sanctity of GDP figures is rarely questioned. These numbers serve as a key barometer of economic health, a policymaking compass, and a symbol of national wealth. But what if these figures are misleading? What if, rather than being a reflection of our true economic condition, India’s GDP numbers are built on statistical sand?

Sabeer Bhatia, the co-founder of Hotmail, recently delivered a scathing critique of India’s GDP computation, calling it a case of basic maths gone awry. He remarked, “The whole country is lying, our GDP is all wrong.” Though his comments were made in a casual podcast, they strike at the heart of an unsettling truth—that our national income accounting may be flawed.

READ I India looks to plug loopholes in free trade agreements

A cloud over GDP growth figures

Let us begin with a technical reality. GDP is calculated through three principal approaches—the output method, the income method, and the expenditure method. Ideally, all three should converge. In practice, they don’t. And when they don’t, governments conveniently insert a catch-all item—discrepancy.

This discrepancy, once an insignificant footnote, has now become a suspiciously large portion of GDP calculations. It is not a real category of output or expenditure; it merely balances the books. In Q1 FY2023-24, India’s GDP was reported to grow at a robust 7.8%, but some economists argue this includes an overstatement of at least one percentage point, attributed largely to this statistical sleight of hand.

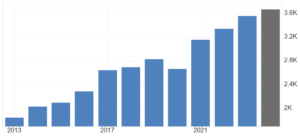

India gross domestic product ($ billion)

Why does this matter? Because if GDP is inflated through accounting tricks, it misguides policy, masks distress, and creates a dangerously misleading image of the economy’s vitality.

Ghost companies of MCA21

In 2015, India overhauled its GDP computation methodology. The Central Statistical Office (CSO) adopted the United Nations-recommended GVA method, changed the base year to 2011-12, and switched to data from the Ministry of Corporate Affairs’ MCA21 database. Theoretically, this brought India in line with global best practices.

But there was a problem. The new database included over 500,000 companies, many of which were found to be non-existent or inactive. A 2016 survey by the National Statistical Organisation itself admitted that several firms in the sample couldn’t be traced or had no meaningful business activity. These phantom firms, nevertheless, contributed to our GDP figures. One doesn’t need a Nobel prize to understand what this does to data credibility.

When concerns were raised, former RBI Governor Raghuram Rajan and then Chief Economic Adviser Arvind Subramanian both criticised the opacity and haste with which the new series was introduced. The controversy deepened when the backdated GDP series made the UPA-era growth look worse and the NDA-era growth appear heroic. The data, in short, seemed too politically convenient to be purely empirical.

GDP that counts transactions, not work

Bhatia’s core critique is philosophical and perhaps the most damning. In India, GDP is being computed not on the basis of real human effort, but on transactions. If I pay you Rs 1,000 and you return the same amount, both get counted—thanks to GST—towards GDP. No goods have been produced, no services rendered. Yet the economy appears to grow.

Contrast this with the United States, where GDP estimation is rooted in actual hours worked and value created per hour. In that sense, the Indian model rewards motion, not progress. We celebrate activity without interrogating whether it leads to productivity or improved well-being.

The deflator debate

Another flaw is embedded in how we transition from nominal to real GDP. This requires a deflator to strip out inflation. But India’s inflation indices are outdated and mismatched. In Q1 FY2023-24, consumer inflation hovered around 4.5%, while wholesale inflation was negative. Depending on which index you use, India’s real GDP could be under 4% or over 8%. The reality lies somewhere in between, but the government, unsurprisingly, prefers the rosier figure.

It is not merely a statistical dilemma. It is a question of institutional integrity. India still uses the Wholesale Price Index (WPI) for several deflators, a tool experts have long called obsolete. It doesn’t disaggregate rural-urban data, lacks granularity, and ignores regional inflation trends. Until we move to a Producer Price Index or update our consumer baskets, the GDP number remains deeply compromised.

Silence of surveys and the question of autonomy

Perhaps the gravest danger is the erosion of our statistical institutions. The merger of CSO and NSSO into the NSO stripped away their autonomy. Reports that challenge the official narrative—like the 2017-18 consumption expenditure survey—are suppressed or delayed. As Pronab Sen, former Chief Statistician of India, observed, the problem isn’t faking data—it is the wilful neglect of inconvenient evidence.

Even the 2021 Census remains undone. The last comprehensive survey of the unorganised sector was in 2015. In a country where 90% of the workforce is informal, how can we claim accurate national accounts without fresh data?

GDP as a mirage of progress

Let us be clear. GDP has value. It helps compare economies, informs policy, and allows for historical tracking. But it is not infallible. It tells us how much we produce, not whether we are better off. It doesn’t measure inequality, environmental degradation, or unpaid care work. It doesn’t capture whether our children are better educated or if our air is breathable.

To keep glorifying a flawed number while ignoring jobless growth, rural distress, and rising inequality is to confuse GDP with development.

What must be done? First, update the base year to reflect current economic realities. Second, restore the independence of statistical bodies and publish suppressed surveys. Third, reform inflation indices and transition to a more robust Producer Price Index. Finally, consider tracking human effort—actual hours worked—as a supplementary indicator, as Bhatia suggests.

And perhaps most crucially, we must remember that GDP is a tool, not a trophy. If we treat it as the ultimate goal, we risk building an economic house of cards.

It is time we stopped congratulating ourselves on questionable numbers and started asking harder questions about what they truly represent. The credibility of our data is the foundation of sound policy—and a nation that seeks greatness cannot afford to build on illusion.