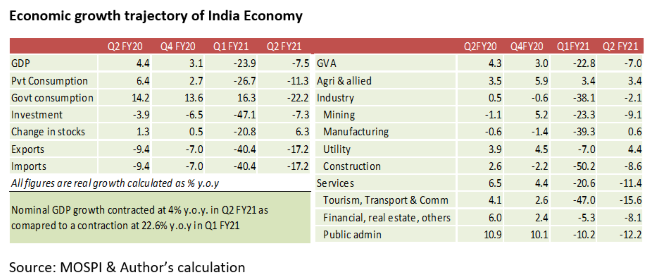

Indian economy contracted 7.5% year-on-year in the second quarter of the current financial year, compared with a slump of 23.9% in the first three months. With this, the economy has entered a phase of technical recession. The deceleration of the Indian economy is one of the sharpest among all major economies, while China, Taiwan and Vietnam reported positive growth. Despite the pace of contraction has slowed down during the quarter, economic recovery is highly uneven with agriculture, utility services and manufacturing are the only sectors showing positive growth.

The whole component of service sector remained in the red, highlighting enhanced challenges for the sector in making a turnaround. Expenditure cuts by both the private sector and the government suggest a weaker aggregate demand prevailing in the economy. Given these prints how smooth would be Indian economy’s recovery from the crisis triggered by the Covid-19 pandemic? What could be the drivers and drags going ahead?

READ I Covid-19 vaccines: The beginning of the end of the pandemic?

The state of the economy

The persisting spread of the coronavirus pandemic continues to exert pressure on growth as it warrants certain kind of restrictions at the local and regional levels. Thus, lockdown stringency index has not eased fully and currently stands at a medium stringency of 61.6, serving as a hindrance to full-fledged economic activities, compared with the pre-Covid levels. It has a larger bearing on the current and medium-term course of the economy. In addition to that consumer sentiment continues to be tepid due to uncertainty over unemployment levels. Google mobility data indicates that in October, the public movement has increased around groceries, pharmacies and residential places above pre-Covid levels, but remained lower at workplaces, areas of recreation and around retail shops.

For deeper insights into the recovery path, the Reserve Bank of India initiated a ‘now-casting methodology’ for predicting the current or the near future economy. The results of this exercise suggested that for non-financial companies, sales continued to be moderate, but expenses fell faster resulting in registering operating profits. For manufacturing companies, leverage ratio decreased, meaning they reduced debt over equity or their assets. In a highly negative and uncertain environment, reduction of debt generally happens as they cut down their business expansion or venturing out plans.

READ I A confident India must join RCEP, other trade blocs

The manufacturing companies also reduced their existing assets further for mobilising funds. Capex done by these companies also remained muted ever since the pandemic hit. As per RBI’s findings, the funds mobilised this way might have been utilised to cut down their existing liabilities and increase cash holdings. During uncertain times, even individuals and corporates undertake precautionary savings by increasing the cash balance. In short, a positive growth in manufacturing was mainly on account of a cut down in operating expenses and reduction of inventories.

For financial companies as well, operating profits increased on the back of asset sales and moderation of expenditure on account of less interest expenses. The marginal rise in provisions for advances resulted in a rise in net profits too.

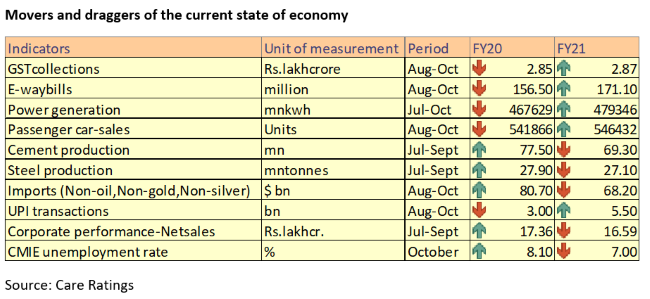

The performance of certain indicators such as Index of Industrial Production (IIP), Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI), growth in retail sales, GST collections and e-way bills as well as certain high frequency parameters might have painted a recovery picture. However, the phenomenon of pent up demand – a sudden surge in demand followed by a slump, at play which seems to have pushed up economic activities. Parameters like cement and steel production, non-oil and non-gold imports, as well as net sales (a proxy for corporate performance) show inherent lack of demand in the economy.

READ I Changing tack: Poverty action in the time of Covid-19 pandemic

Growth outlook

Given these factors, recovery seems to be protracted and it may even delay further with inadequate fiscal stimulus, restricted monetary actions and muted export growth. Agriculture is the only silver lining and the evidence is quite strong from the first advance estimates of the summer harvest, which is the weighted average growth of 7.3% in production of oil seeds and sugar cane. More people available for agriculture due to reverse migration may help to some extent until their marginal productivity becomes zero. The marginal growth in manufacturing is transient as companies reduced assets and cut down inventories. This may not be sustainable without adequate policy measures to give further impetus for the sector.

Persisting inflationary pressure both from food and core prices poses further downside risk for the economy. Inefficient supply management and role of middlemen may amplify the food price pressure further. The next wave of virus spread is another major risk for the economy domestically and globally, impacting the export prospects for the nation. These stress points could have a spill over effect on the financial sector, owing to the risk averse behaviour of households and corporates. If at all the recent recovery points have to be sustained, it should be more than just pent up demand – it must come from the economy driven by inherent demand.

Dr. Aswathy Rachel Varughese is Assistant Professor at Gulati Institute of Finance and Taxation, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala.