In September 2010, The Economist carried a cover story on why Indian economy will overtake China’s. The magazine cited two reasons for India’s economic miracle — demography and democracy. The article said the ageing China with a shrinking working age population will cede ground to India’s demographic dividend. It said India’s economic liberalisation resulted in the emergence of strong businesses and a confident English-speaking elite, giving it an edge over China. The article was followed by a number of similar writeups in the western media, and the local media went into an overdrive of triumphalism.

Eleven years have passed. The world’s confidence on Indian miracle seems to have waned. The economic slowdown triggered by the demonetisation in 2016 and the hurried rollout of the Goods and Services Tax had taken the sheen off the Indian economy when the Covid-19 pandemic struck. The worst health crisis since the Spanish Flu of 1918 wreaked havoc among India’s small businesses, leading to massive job losses and poverty.

For most of the known history of the world, China and India were the largest economies. The emergence of Western colonial powers saw them becoming laggards. Both the countries had similar GDPs when they embarked on different paths in their quest for economic prosperity. China was early to start off on the reforms path and left India behind in the 1990s. The next two decades saw Indian economy doing some catching up, leading to an optimism that resulted in the western media hailing its slow, but steady economic transformation.

The size of Indian and Chinese economies was $189 billion and $305 billion respectively in 1980. But in 2021, they are at $2.9 trillion and $14 trillion. Is India capable of emulating the Chinese miracle and overtaking it eventually.

READ I Ease of doing business: Why World Bank should exit ranking efforts

Demographic dividend

Chinese leadership has already started addressing its demographic demons. It is already on course to reverse the infamous one-child policy, while India seems confused over its population policy. India will become the world’s most populous country with around 1.7 billion people in another three decades. The huge working age population is a good starting point to become a global economic powerhouse. The Indian working age population will grow for another 24 years before peaking at around 1.15 billion in 2045.

While some states like Kerala managed to tap the demographic dividend and created an education and health infrastructure, several northern and eastern states are busy fighting the demons of caste and religious strife.

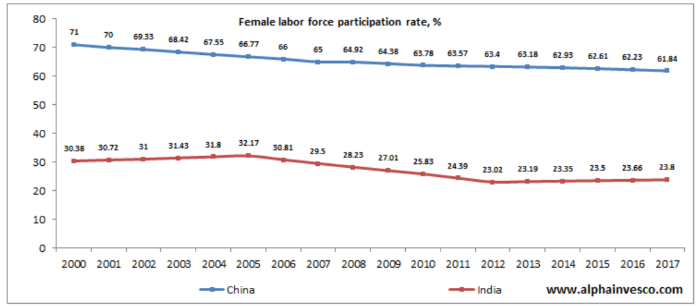

The years of uninterrupted growth helped China add 375 million jobs between 1978 and 2017. It added 13 million jobs in each of the five years between 2014 and 2019, it added 13 million jobs. The industrial sector enjoyed an uninterrupted supply of cheap labour from agricultural sector that was facing disguised unemployment. This was made possible by massive investments in education and the health since 1980. India’s female labour force participation rate is 43% compared with 70% in China. India needs heavy investments to match up to China on this count.

There is a possibility that India may fritter away its demographic dividend without adequate investment in health and education. Population has stabilised in many of its economically better performing states, while the socially and economically backward states still witness rapid population growth. Such imbalance could lead to social and economic strife and turn the young population into a liability.

READ I COP26: Green hydrogen gets a leg up at climate change meet

Infrastructure development

In the last four decades, China has created a world class physical and social infrastructure, a business climate conducive to investment, and a powerful manufacturing industry. India’s achievements in these three areas are nothing to write home about. While both the countries started their journey of modernisation around the same time, China managed to outpace India in every aspect of economic progress.

Chinese investment rate is among the highest in the world. This has helped China to build a world class infrastructure including highways, high-speed rail, airports and ports. It also created a robust manufacturing industry that made it the world’s factory. It also invested heavily in health and education, supplementing the progress it made in physical infrastructure. Steady flow of educated, healthy workers helped the economy to grow in double digits for a prolonged period without stoking inflation. The Chinese miracle was made possible by the heavy investment made by the government on physical and social infrastructure.

Indian economy lags behind China in terms of investment. It has an investment rate of around 30%, far behind China’s 50%. India’s manufacturing industry contributes a fifth of the economy, while it is almost a third in the case of China. India’s physical and social infrastructure is a reflection of its economic problems. But, if India manages to attract funds into its infrastructure sector, it can create an economic miracle of its own.

READ I TechFins: Why India must stop their unregulated, untaxed run

Democratic edge

The jury is still out on whether democracy is good or bad for economic development. While it is widely assumed that the developed democracies prefer to do business with their counterparts in the developing world, empirical evidence suggest that they go for the cheapest bidder.

India, however, always enjoyed a moral edge in its dealings with the rest of the world because of the legacy of its freedom movement. This moral edge and a functioning democracy allowed it to have an influence in world affairs disproportionate to its economic power. India needs to strengthen its democratic institutions to sustain this influence. The government must address the rise in sectarian violence and bigotry.

Reforms in Indian economy

As the country is limping back to normalcy after the devastation caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, it needs policies to accelerate growth. The Narendra Modi government has initiated a number of policy and institutional reforms amid the pandemic crisis. The steps initiated by the government include opening up of the defence sector, labour reforms, agricultural reforms, financial sector reforms, and raising the FDI cap in insurance to 74%.

While the merit and quality of some of these reforms are still being debated, no one can deny that there has been a push for private sector investment, which is key to Indian economy’s long-term growth prospects. The reforms agenda is unfinished — the Union government needs to undertake GST simplification and Direct Tax Code, while states will have to work on land reforms.

The emergence of Indian economy will be powered by the corporate sector and the Micro, Small & Medium Enterprises, not by government investment. Though there is considerable improvement in ease of doing business in the last two decades, there are still some bureaucratic hurdles that stop people from taking up entrepreneurship. The government needs to create a world class infrastructure and investment climate to allow businesses to prosper.

The Indian economy needs to grow at high single digit rates for at least two decades for it to emulate the Chinese miracle. India may eventually become an economic superpower by the sheer weight of its population, but the path will be thorny and the pace will be slow.

Anil Nair is Founder and Editor, Policy Circle.