The Narendra Modi government took everyone by surprise by taking a U-turn on the controversial farm laws. In his address to the nation last week, the prime minister announced the repeal of the farm laws, a demand which the government has been steadfastly resisting for over a year. The three laws met with unprecedented resistance by tens of thousands of farmers over the last one year. The decision is seen more as political manoeuvring before the elections to Uttar Pradesh and Punjab assemblies next year. The BJP faced reversals in recent assembly elections and Uttar Pradesh is a battle it cannot afford to lose.

In September 2020, the Union government passed three farm laws which, according to the government, were aimed at helping the country’s farmers. But there was hardly any consultation with stakeholders before the government brought in the laws. The move triggered a massive stir as farmers were convinced that the new laws will destroy their livelihoods.

READ I Repeal of farm laws will impact the future of agriculture reforms

Three farm laws explained

Simply put, the first law — The Farmers Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, 2020 — allows farmers to sell their harvest outside the government-authorised mandis without paying state taxes or fees. Under the second law — The Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Act, 2020 — farmers can directly sell their produce to companies. They can also enter into exclusive contracts where they agree in advance to plant and harvest crops, and sell their produce at the prevailing prices.

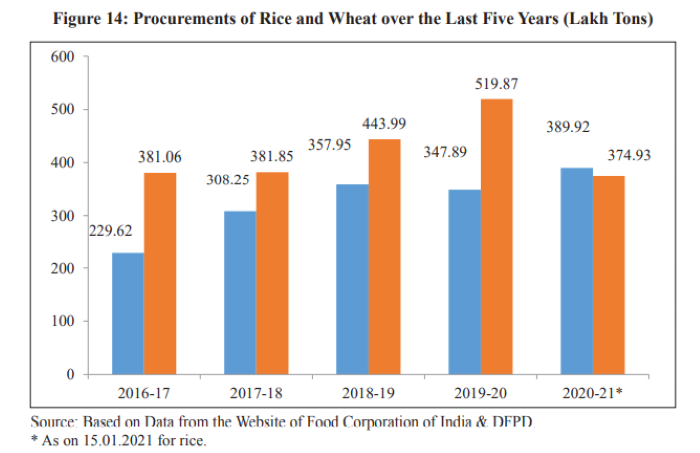

The third law — The Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act, 2020 — removes all curbs on storing major foodstuff including cereals, pulses, edible oil and onions, except during emergencies. India is an agriculture-dominated country with nearly two thirds of the population relying on farming for a living.

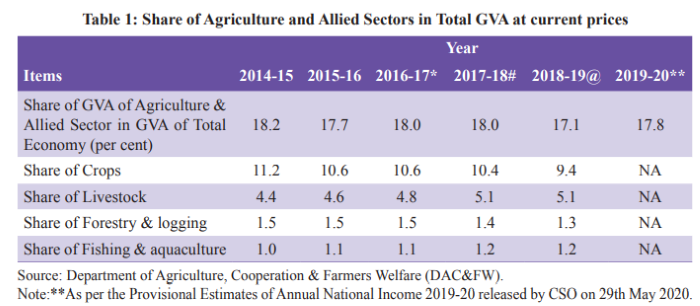

Gross Value Added by agriculture, forestry, and fishing was estimated at Rs 19.48 lakh crore ($276.37 billion) in FY20, according to IBEF. However, farming has not been a profitable enterprise with up to 86% of all farmers having small or marginal plots of land and modest harvests. Farmer suicide has been an issue since the 1970s as the agrarian community makes little money, estimated at Rs 6,426 per month in 2014. To make matters worse, agriculture in India is heavily dependent on weather, cost of seeds, and fertiliser prices.

READ I Agrarian crisis: FPOs is the way out for Indian farmers

Why farmers are angry

While there is nothing wrong with the laws on paper and the government has been insisting that they will benefit farmers who will get a better price for their harvest, the farmers remained unmoved. The farm laws were initially introduced as reforms amid the COVID-19 outbreak in early 2020. At the time, there were token protests against the ordinances. However, when the government moved them as Bills in September 2020, it faced protests in Parliament. The ordinances then became Acts.

According to the new laws, farmers were allowed to sell their produce directly outside mandis, but farmers say they are free to do the same even without these laws. However, usually they sell their harvest at government-notified mandis where the role of middlemen comes into play. These middlemen then sell the grains and vegetables to wholesalers and retailers.

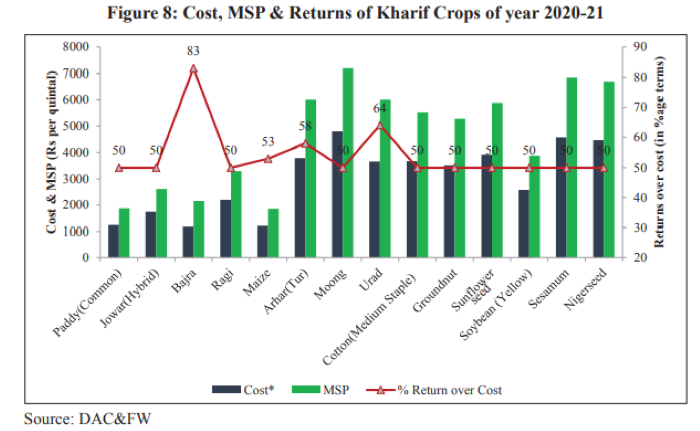

Further, the Minimum Support Price, or MSP, is also at the core of the confrontation between the farming community and the government. The government is liable to purchase 23 crops at an already settled price in case a farmer fails to sell his harvest to the market. This acts as a safety net that ensures the farmer will at least recover his costs.

READ I India’s fledgling e-commerce industry needs a robust policy framework

The government has maintained that it will not scrap MSP. It claimed that the elimination of middlemen would allow farmers to directly sell to buyers at better prices. Farmers anticipated a few scenarios that could affect them. If private companies enter the market and start striking deals with farmers directly, the government-run mandis are likely to become obsolete and, therefore, the MSPs would no longer apply. In a country where the farming community is already at the mercy of several factors and does not have the power to negotiate a fair deal with companies, it will soon find itself in an even more miserable situation.

To some extent, these worries have played out in real life as well. Due to the lockdown of mandis, many states allowed farmers to directly sell their harvest, but they ended up receiving 10-15% lower prices compared with the MSP. However, in states such as Haryana and Punjab where the government is committed to buying the entire harvest from farmers, there was no effect on the prices as the farmers were not dependent on other buyers.

The farm laws could have worked for the farmers even in the previous forms had they collectively bargained the prices of their produce, like how monopolies or cartels work. The state governments were also unhappy with the laws. They make a hefty amount in mandi fees. For instance, the Punjab government charges a 6% mandi tax plus a 2.5% fee from the Union government. The same adds up to an annual revenue of about Rs 35 billion. The middlemen also refused to play along with the government as they profit at the expense of farmers.

Narendra Modi’s retreat

The surprise decision to roll back the farm laws has come without any official reason as to why they were rolled back even though the government had earlier called them historic. The announcement was made just before the crucial Assembly elections in Uttar Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, Uttarakhand, and Goa. The government is facing stiff opposition from various parties.

The Union ministers and BJP leaders are still convinced that the three farm laws are beneficial to the farmer. They feel that the government could not convince a section of farmers despite its best efforts. While welcoming the withdrawal of laws, UP chief minister Yogi Adityanath said the government could not explain the benefits of the laws to the people.

After announcing the repeal of the farm laws, Modi urged the protesting farmers to return to their land. But farmer leader Rakesh Tikait said that unless something concrete is done in the Winter session of Parliament which is scheduled to commence on November 29, the farmers will stay at the protest sites.

Farmers are also holding fast to their core MSP demand — that the Minimum Support Price be made universal, within mandis and outside. This essentially means all sales to buyers, whether the government or private, cannot fall below the settled minimum rate. Moreover, the agitation is also expected to continue until the withdrawal of the Electricity Amendment Act.

The decision to repeal the farm laws could dent Modi’s image as a leader who will not back down on his decisions. He did not apologise for the disastrous demonetisation in 2016. He did not relent on the Citizenship Amendment Act or the withdrawal of statehood and special status to Kashmir despite massive protests. This is why many see the Prime Minister’s apology as a tactical withdrawal and not as a surrender.