“Now wash your hands.” Often seen on the walls of public toilets around the world, this phrase highlights how vital handwashing is in preventing the spread of disease. Yet for millions of people, the signs might as well say “Now fly to the moon.” At the current rate of progress, only 78% of the global population will have basic handwashing facilities by 2030, leaving 1.9 billion people at risk from illness and disease.

At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, health experts highlighted handwashing as a key measure, yet an estimated 3 in 10 people worldwide were not able to wash their hands with soap and water at home. The situation in health facilities is also dire. One in four lack basic water services, and one in three lack hand hygiene facilities where care is provided, meaning health centres risk becoming breeding grounds for illness.

Handwashing campaigns have pushed for equitable, affordable access to clean water, sanitation, and hygiene, or WASH, services – including in health-care facilities and schools – for many years. Successes include programs like the Hygiene Behaviour Change Coalition led by the U.K. Government, Unilever, and London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, which reached one billion people through hygiene behaviour change during the pandemic.

To make this a reality, however, for everyone, everywhere – both now and in future health emergencies – a concerted global effort is required, with targeted investments by national governments playing a key role. For too long, hygiene services have been overlooked and underfunded. For everyone to have somewhere to wash their hands at home by 2030, we need to start making progress in some areas up to four times faster.

READ I Adolescents not well served by responses to Covid, climate change

A failure to invest in handwashing

What are the consequences of failing to invest in this basic public health measure? Lack of clean running water has negative consequences for gender equality. Women and girls bear the greatest burden of domestic chores, and may spend hours every day trekking on foot to collect water. As a result, many girls miss schooling or even drop out altogether.

At a wider level, communities, businesses, and even whole countries’ economies simply won’t be resilient to shocks or health crises. In 2016 alone, 165,000 deaths from diarrhoeal disease and 370,000 deaths from acute respiratory infections were attributed to inadequate hand hygiene. So, what will it take to give the whole world access to WASH services – especially in homes, communities, health facilities and schools?

A recent report by the World Health Organization and UNICEF reveals that ensuring everyone in the poorest countries has somewhere to wash their hands with soap and water at home would cost around $11 billion per year until 2030 – that is equivalent to the amount spent during Amazon’s Prime Day shopping event in June. Bringing WASH services to all health facilities and hospitals in the world’s 46 least developed countries would cost about $9.6 billion over a decade.

These are still sizeable investments, but the potential health and economic benefits – a hygiene dividend – are enormous. Research by Vivid Economics and WaterAid found that universal access to soap and water at home for handwashing could generate a net benefit of $45 billion per year. Providing safely managed drinking water for every household could yield $37 billion per annum. To achieve these investments requires smart, catalytic finance from the major economies in the G20 and by other governments. The Global Health Security Financial Intermediary Fund hosted by the World Bank also has a key role to play.

READ I Battle over farm laws may just have ended in stalemate

The time is now

Next week, on November 29, the World Health Assembly will host a special session on the pandemic preparedness treaty. We need better early warning and surveillance. But to be successful we also need to harness the kind of global collaboration and innovation seen in the rapid development of COVID-19 vaccines. We need partnerships to produce and distribute high-quality, affordable hand hygiene products and services. Achieving affordable access to soap and water for everyone is far simpler than developing a new vaccine – although we must ensure more equity than has been seen to date in the roll-out of vaccines.

Our efforts should focus on poor and vulnerable communities, including women, children, and adolescents in those communities. In particular, we should target people in fragile and humanitarian settings, given the greater impact of COVID-19 on these groups and the lack of WASH services. In these settings, people are twice as likely to lack access to safely managed water services.

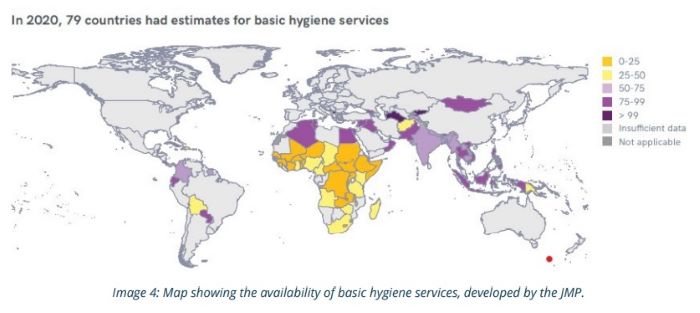

Finally, we need more high-quality, disaggregated data to identify WASH coverage gaps, track progress, and inform decision-making. Next year’s G20 chair, Indonesia, has demonstrated how an innovative digital health strategy can crowdsource data on hand hygiene in public spaces and strengthen monitoring systems in hospitals. Similar initiatives are especially needed in low-income countries.

COVID-19 has shone a spotlight on handwashing and ways of getting clean water and soap to billions of people who need them. It has highlighted the importance of sustaining behaviour change and implementing policies that make this possible. The next global health crisis may come sooner than we think. To be ready, we need to fix hand hygiene once and for all.

(Helen Clark is board chair of PMNCH and co-chair of IPPPR. She served as prime minister of New Zealand from 1999 to 2008 and as administrator of the United Nations Development Programme from 2009 to 2017. Ellen Johnson Sirleaf served as president of Liberia from 2006 to 2018. Sirleaf was a recipient of the 2011 Nobel Peace Prize. She is the founder of the Ellen Johnson Sirleaf Presidential Center for Women and Development and co-chair of IPPPR. This article was first published on Devex.com.)