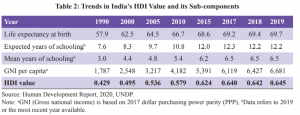

Budget 2022 and social sector schemes: India presents a paradoxical human resources situation. On one hand, it produces the maximum number of Fortune 500 CEOs while on the other its enterprises are struggling to find the required number of skilled workers. Like in the case of other developing countries, India also suffers from unequal distribution and growth of human resources. It has made gains in reducing poverty, increasing literacy and access to healthcare, but failed to repeat this success when it comes to human resources development.

India is a young nation with a median age of 28 to 29 years. More than 60% of the population is in the working age or aged between 15 and 59 years. India is expected to benefit from demographic dividend, the potential economic benefit from its young population. The National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5) revealed a 2.1% (28.6% to 26.5%) fall in the share of population below 15 years over the last five years (2016-2021).

This decline indicates that the window of demographic dividend will close progressively in a few decades and society will witness increasing age dependency ratio, which stands at 49% at present. Unlike in countries like Japan, the chances of older people staying in the workforce is less because of the lack of quality labour and a mismatch with the growing demands of skilled manpower.

READ I An unkept promise: What derailed the Indian Economy

Another serious concern is that the share of stunted (height for age), wasted (weight for height) and underweight (weight for age) children in the country are 35.5%, 19.3% and 32.1% respectively. These figures show that less capable children who will grow to constitute a significant part of the workforce in the coming decades. This will not only hinder the equitable growth of the nation, but also increase the prevailing inequality.

Similarly, women and men whose body mass index is lower than average (18.5kg/m2) and or are obese (BMI>25kg/m2) constitute 40% of the population, which present a gloomy picture of quality of life in India.

Focus on quality missing

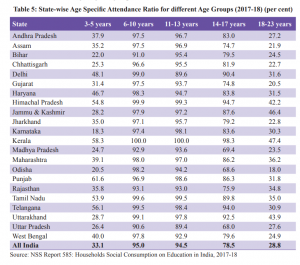

Education is an outcome as well as an input indicator of human development. The last Economic Survey (A158) says the enrollment ratio over the cumulative stages of educational acquirement (elementary, secondary, senior secondary and higher education) experiences a gradual decline of 20%. This highlights the reluctance in getting higher skills because of various reasons.

India’s literacy rate has increased six times since independence and stands at 74%, with a high interstate inequality – the figure for Kerala being 94%, while that of Bihar being 64%. Similarly, higher education, which actively contributes to the workforce and to the nation’s growth is suffering in terms of low enrollment, poor quality and disbursement of employment-friendly skills.

On the research and development front, doctoral programmes, which contribute up to 65% of the total research output, account for 0.5% of total enrollment. The brain drain situation of India shows a precarious overseas preference of Indian productive human capital in terms of both employment and higher education.

READ I Budget 2022 may shift focus to asset management

These figures show that though India has managed to improve education in terms of quantity of human development, it failed to improve the quality to achieve global standards. In ensuring quality of human resources, planning and implementation of policies play a major role. This article studies budgetary allocations and fiscal interventions to suggest ways to build a capable, informed and able workforce.

Budget 2022 and quality education

The Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG-4) defines education as a basic right and elementary to human dignity. It seeks to ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all. This plays a central role in building sustainable, inclusive and resilient societies. The Indian education system has a major quality problem, with the country’s youth failing to match the needs of the job market.

Inequality in terms of access to employment opportunities (inequalities of opportunity and outcome) has increased after economic reforms. As per the last budget estimates, the demand for grants for school education stood at Rs 54,873.66 crore, while the same for higher education stood at Rs 38,350.65 crore. Capital estimates for school education stood at zero and that for higher education was at Rs 25 crore only.

These figures are the result of low allocation of GDP (3%) to the education sector. School and primary education have been given the utmost importance with 59% of the budgetary grants, while higher education gets 41%. Though higher education has lower enrolment, the linkage of higher education with human development is more crucial. It is undeniable that school education holds the impetus for higher education, but it is equally important to fund higher education, not only to increase enrolment but also to infuse quality.

READ I Vaccine hesitancy in rural areas threatens India’s Covid-19 response

A significant part of education is research and innovation. Student financial aid disbursed (of which a significant portion is research fellowships) constitutes just 3% of the total grants to education. This compares poorly with global standards. Over the years, the focus of research has shifted towards defence innovations and the growth in health and socio-economic research does not look impressive. Funding of research and programmes for quality assurance in remote education should form a significant part of Budget 2022.

Quality monitoring of educational programmes demands allocations in the upcoming budgets. Monitoring of education delivery should not only aim to maintain quality but also aim at improving existing educational standards in line with emerging knowledge and needs of the society. In this case, policies cannot be universal because of the prevailing inequalities.

Budgeting quality healthcare

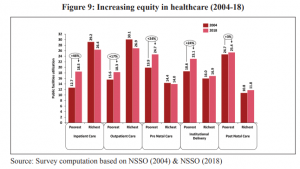

Health is a complex interplay of biological, socio-cultural and environmental factors that support and improve growth in other dimensions of human development. Like education, health is also affected by other factors such as poverty, inequality and accessibility. The Sustainable Development Goal – 3 (SDG 3) looks to promote health at all ages. The pandemic may have stalled or reversed decades of progress in reproductive health, mental health and child health.

Low- and middle-income countries have been able to meet their healthcare goals, but changing health needs and growing public expectations have shifted the focus to the quality, accessibility and inclusivity of healthcare. Accessibility to healthcare without quality is meaningless and the situation gets worse when quality only becomes a hallmark for the elites.

India spent 1.8% of its GDP on health in 2020-21; it was 1-1.5% in the previous years. This is among the lowest percentages any government spends on health in the world. As a result, India is among the top 10 nations with the highest out-pocket expenditure.

READ I Niti Aayog’s state health index will push data driven approach

Recommendations for increased allocation of funds for health have been hugely neglected. The chinks in health infrastructure were exposed by the pandemic. On one side, there are villages with no hospitals and on the other, there are posh hospitals with advanced facilities that cater to the well-to-do population. The allocation of funds should aim at bridging this gap and ensuring quality healthcare for all. Quality healthcare is intergenerational, meaning that a generation of well-to-do families will earn well thus will build a further healthy generation.

Fiscal allocation on the sustainable growth of a healthy population requires to be both universal and specific. In the larger sense, Universal Health Coverage (UHC) is of paramount importance for ensuring quality healthcare. However, targeting healthcare through government schemes without quality monitoring will lead to the wastage of revenue.

Role of monitoring and evaluation

Monitoring and evaluation are of paramount importance in disbursing quality social services. Allocation of funds towards separate monitoring bodies for different social services will induce strategic planning with linkages between interventions and outcomes. Similarly, enhanced accountability and legitimate usage of public funds will certainly enhance policy efficiency.

Under NITI Aayog, the Development Office and Evaluation Monitoring (DOEM) is entitled to similar duties and the scope for intervention is limited. There is an evident reluctance among states towards effective monitoring policies, which needs to be addressed immediately.

Lastly, provisions in the budget for quality education and healthcare will have a positive recurring long-term impact on the economy. As they are highly linked variables of human development, they will induce growth in other sectors as well. Moreover, quality monitoring and evaluation of all segments of public policies are needed for effective delivery of services to the intended group of citizens.

(Kaibalyapati Mishra is a research student at the Centre for Economic Studies & Policy, Institute for Social & Economic Change, Bengaluru.)