Sri Lanka is in the midst of its worst financial crisis since it gained independence in 1948. The country is facing shortages of essential food items and fuel as it is unable to pay for imports. The government had to cancel school examinations as it ran out of paper and could not afford imports. The crisis was in the making for some time, but the pandemic exposed the fault lines in the economy, triggering its collapse.

Though Sri Lanka is categorised as a low-income country, it has done exceedingly well in terms of social development indicators. Over the years, its performance has only improved. In 2020, life expectancy in Sri Lanka was 77 years, compared with 75 years in 2015. Similarly, adult literacy rate was 92% in 2020, up from 91% in 2015. The island nation also did well on other parameters such as mean years of schooling and sex ratio, setting itself apart from its South Asian neighbours.

The Sri Lankan government initiated the first round of economic liberalisation in 1977, much ahead of its neighbours. The reforms, supported by the IMF, saw investment doubling to 30% of the GDP. The economic growth rate doubled as agricultural and manufacturing sectors responded positively to improved incentives. The country set an ambitious plan to become an upper-middle-income economy by 2025 by transforming itself into an Indian Ocean hub for trade, investment, and services. But this plan glossed over several structural and competitiveness-related challenges.

READ I Easing of public debt burden will cause economic disruption

A nation is like a joint family where each micro-unit has separate roles. If one unit fails in its duty, the entire family will be impacted negatively. Sri Lanka, a nation of 22 million people, is currently experiencing the consequences of such a failure. The crisis in the Sri Lankan economy is the result of a string of decisions made by President Gotabaya Rajapaksa and his ministers who are mostly his brothers and nephews. The other pillars of the state — the executive, judiciary, civil society, and the media — remained mute spectators and did not voice their opposition.

Some of the factors and decisions that led to the current crisis are cutting taxes, printing currency to boost growth, focus on organic agriculture and banning the use of chemical pesticides/fertilisers, debt-based financing of ornamental infrastructure projects such as highways, airports and ports, and dependence on the service sector leading to a changed work culture. The government’s dependence on external consultants (some of them being private) can also be blamed for the sorry state of affairs in the Sri Lankan economy.

READ I Timely action on inflation needed to avert hard landing: Maurice Obstfeld

Sri Lanka’s payment crisis

The most significant cause of the crisis is wasteful investments in large infrastructure projects. Other reasons are overdependence on remittances and service sector revenues, holdings by tax havens and exports of select agricultural products. Nearly three decades ago, international organisations guided Sri Lanka’s liberalisation, which led to an increased dependence on tropical agriculture and exports mainly to developed markets.

The double standards in evaluating progress in non-trade issues such as achievements on the human rights and climate change action fronts forced the government to put excessive stress on organic farming. Ironically, such violations by China are ignored as most joint ventures there are partially owned by US-based firms.

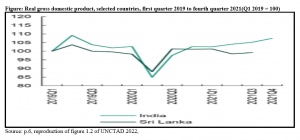

The economy is burdened by the rising debt-to-GDP ratio (102%) and repayment commitments of $7 billion to lenders from China, India, Japan and the IMF. Covid-19 had an adverse impact on both the GDP and employment in Sri Lanka. The pandemic pushed the economy into a vicious cycle, with travel restrictions leading to a fall in foreign currency reserves and weaker currency and broken supply chains leading to a swollen import bill.

The shortage of reserves led to the scarcity of critical commodities like diesel, cooking gas, vegetables, cereals, and medicines. To make things worse, there has been a decrease in electricity generation, resulting in blackouts of up to 7.5 hours a day. This impacted the industry and hit small businesses. The Easter terrorist attacks in 2019 and the Covid-19 pandemic hit the flourishing tourism industry which is also a substantial earner of foreign exchange.

Depleting forex reserves and the depreciating currency made debt repayment difficult. This led to further depletion of currency value against the dollar. The rupee, which stood at 198 a dollar in 2021, slipped to 290 in March 2022. The sudden surge of Rs 92 from March 7 led to a spike in the prices of essential items such as milk, rice and vegetables. One crisis triggered another, leading to a chain of collapses. Within days, the whole edifice crashed.

Lessons from the Lankan fiasco

A comparison of export sectors in Sri Lanka and India shows a drop in the number of competitive sectors between 2000 and 2020. In 2009, Sri Lanka had a comparative advantage in eight sectors, namely coffee and tea, clothing, agricultural products, beverages and tobacco, leather and footwear, manufactures not-elsewhere-specified, wood products, and non-electrical machinery.

By 2020, the list had only five items – coffee and tea, clothing, agricultural products, leather and footwear, and wood products. Many of these belonged to the perishable goods segment with less than six weeks of shelf-life. Import-dependent food habits that encourage homogenisation need to change. The government needs to promote heterogeneous eating habits.

Sri Lanka did not have any programme to complement the liberalisation efforts. India introduced programmes such as Vocal for Local, PLI scheme and Atmanirbhar Bharat along with the opening up of new sectors. Manufacturing and agriculture are vital sectors and can generate significant employment opportunities and push aggregate demand.

After nearly two decades of internal strife, the priority of Sri Lanka should have been to strengthen the functioning of the four pillars of the state. The lack of effective interventions reduced the country to a dictatorial democracy where a single-family controlled all critical functions. All such countries are bound to fail sooner or later. Globally, a large number of economies are on the verge of default due to the disastrous Russia-Ukraine war hitting them before they could fully recover from the post-Covid paralysis.

Murali Kallummal is Professor, Centre for WTO Studies, CRIT, IIFT, New Delhi. Views are personal.