Mani Ratnam’s epic film Ponniyin Selvan has attracted a lot of attention to the history of Tamil Nadu. The Chola dynasty that ruled between 800 CE and 1250 CE had most parts of peninsular India under its rule. At the peak of its power, Sri Lanka, several parts of northern India and southeast Asia came under Chola rule. The maritime power scripted some glorious chapters of Indian history, but independent India’s history texts have very few mentions of its conquests. For those who are familiar with Chola history, Tamil Nadu’s rise as an economic powerhouse will not come as a surprise.

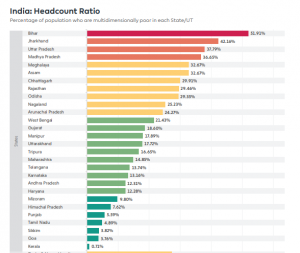

Tamil Nadu is the largest economy among states after Maharashtra. It also is the most industrialised state in India. A vibrant manufacturing sector contributes a third of the state’s economy. Tamil Nadu’s achievements in social sector are even more impressive than its macroeconomic numbers. Only less than 5% of the population are poor compared with the national average of around 20%.

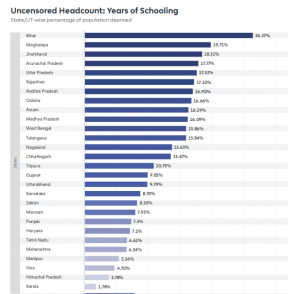

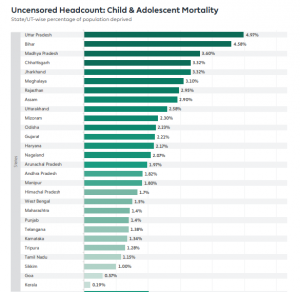

READ I Multidimensional Poverty: Niti Aayog report points to need for course correction

Tamil Nadu: History of progressive governance

While the progressive policies of the state government contributed most to the state’s progress, there are also some historical factors behind its stellar performance. Before discussing the present-day Tamil Nadu economy, it may be relevant to take a look at the historical factors that led to the region’s progress. The invasions that destroyed most of the current Hindi speaking heartland after 1000 CE had little impact here.

The British found an established system of local governance in the region. The earliest record of elections to local bodies is from around the 10th century CE at Uthiramerur. An established land revenue and trade taxation systems provided for revenues to the kings, who spent it on public works like dams, irrigation, roads and temples, similar to MNREGA, during years with poor harvests.

Peaceful coexistence of different religions and communities led to a stable administration with a law-abiding people going about their work under a benign administration. For the British civil servants posted in the south, it was ennui with little to administer compared to the turbulent northern and western regions.

Contribution of community development programmes

Post-independence, the newly launched community development programmes were launched with vigor. The first two decades under Chief Minister Kamaraj saw an emphasis on rural electrification, irrigation and rural roads. The period also saw the expansion of government school system all over the state.

An enlightened health bureaucracy separated the public health and the medical service functions as early as 1955. The focus on small industries and on cotton spinning and textiles took advantage of the large cotton plantations in the state. Sugar factories to crush sugar cane came up. These led to a large number of ancillary engineering industries with the state providing financial incentives and loans.

The real changes in the social fabric occurred after the arrival of the Dravidian parties — the DMK in 1967 and the AIADMK in 1977. Born of similar ideologies with a focus on social justice and social welfare, these parties focused primarily on delivering welfare-oriented policies.

The period represented a paradigm shift. During the Congress administration and earlier under the British rule, delivery of services followed a top-down approach that did not take into account the needs of the citizens. The Dravidian parties changed all that. Fundamentally, the district and sub-district units became influential, needs of the people were taken into account and programmes reflected the needs of the people.

This kind of administration succeeded primarily because the structure of the administrative machinery underwent a radical change. Reservations for backward communities enabled many more candidates from these communities to come up. Given their backgrounds, they were totally in sync with the policies. The lower-level political functionaries could also feel the political clout that the new schemes such as scholarships for the poor, midday meals, and free text books gave them.

Welfare politics played its part

Over three decades, the synergy between welfare policies, administrative delivery, and political advantage worked hand in hand to deliver a host of services to the people. These included education support and hostels, medical aid programmes, grants for the widowed as well as single mothers. All these enhanced the reach of the DMK in the first five years of its rule. The mid-day meals programme of MGR was a game changer in access to services.

Coupled with universal PDS and low-priced rice, child nutrition, free text books, notebooks, and free uniforms helped deliver opportunities for the weaker sections. The MGR government’s focus on higher education enabled tertiary institutions to be set up through private initiatives all over the state. The state now is proud that it has the highest percentile of school leavers going to universities.

A combination of ideology, political will and administrative capacity helped make this social change possible, unique in the country. No other state has had this combination nor the continuity of ideas of governance for over 50 years. Combined with the background of industrialisation started during the Congress era, the state has been able to make significant progress in economic development.

There is a downside as well. Over a period of time, the welfare assistances deteriorated into free grants during election times with both DMK and AIADMK offering more and more freebies. The DMK promised two acres of land for every person, the AIADMK distributed goats, mixies and fans and so on. This led to a drain on public resources, and exacerbated corruption. The concept of clean welfare state is under threat from a free granting, rent-seeking state.

(Dr S Narayan is a retired Indian Administrative Service officer of 1965 batch. His last assignment was as the Union Finance Secretary. Between 1989 and 1995, he worked as Secretary, Rural Development in Tamil Nadu.)