The new coronavirus outbreak has devasted the global economy with many commentators comparing the pandemic with the recession of 2008 and the great depression of the 1930s. Some economic historians have drawn parallels between the current crisis and the World Wars. The gravest health emergency since the Spanish Flu outbreak of 1918 has killed around 1,10,000 people and infected close to 1.8 million. The crisis is far from over with some of the largest economies struggling to cope with the impact of the outbreak. The disease has already infected more than half-a-million people in the United States with the death toll in the world’s largest economy surpassing those of Italy and Spain, the countries most affected by the outbreak.

India took the health emergency head-on with Prime Minister Narendra Modi announcing a nationwide 21-day lockdown on March 25. The timely action proved vital as it managed to limit the spread of the virus. As this article is being published, India has less than 8,500 confirmed Covid-19 cases and a death toll of 273. According to the Union health ministry, the total number of cases would have crossed 8,00,000, had the lockdown not been imposed. The world is hoping that the scientific community will manage to come up with effective medicines and vaccines to check the spread of the disease. While the final impact of the outbreak is yet to be known, it is hoped that India will contain the losses in terms of death toll and economic impact. In the post-coronavirus world, India will continue to benefit from the demographic dividend.

READ: Amid coronavirus gloom, a great opportunity beckons India

The forecasts differ in terms of the possible devastation of the coronavirus outbreak on the global economy. According to various forecasts, the outbreak could shave off 5-8% of the global GDP. Most estimates see India and China faring better than most other countries.

Two factors play an important role in determining the economic growth — capital and labour. In India, capital has always been scarce, but it has an abundance of labour supply. In the current stage of economic growth, India is still largely dependent on the banking system that plays an important role in financing trade, manufacturing and services. The lockdown did impact the banking system in terms of business, though banks still continue to operate essential services.

The government and the RBI have swung into action initiating fiscal stimulus and ensuring liquidity in the economy through both conventional and unconventional methods. The crucial unknown here is that how long the lockdown — total or partial — would last and how long it will take for the migrant labour to return to the work places. In view of the global experience, the lockdown could last 8 weeks and it may take another 4 weeks for the migrant labourers to come back. So, about a quarter of the year would be lost, but the early months of the financial year are considered to be the lean season by economists and policy makers.

READ: Covid-19: Kerala Model is the success of decentralised democracy

The performance of the agriculture sector will be crucial for the revival of economic growth after the lockdown is withdrawn. The rabi crop is now ready for harvest, but as per the practice of national accounts, technically, the standing Rabi crop of March- April 2020 is captured in the output of 2019-20 and not 2020-21. The prediction of a good monsoon by the first week of June raises the hope of a robust kharif crop followed by a good sowing of the next rabi. The production and supply of milk, fruits and vegetables, all classified under essential commodities, continue during the lockdown and there seems to be no threat to these segments.

When the economic activity begins in full swing after the lockdown, we could expect a shakeup in production activity and consumer behaviour. The demand for masks and hand sanitisers are expected to shoot up, with around 100 crore people looking for protection from the virus. Health workers, watchmen, cleaning staff and several other jobs involving mass contact will use personal protection gear. The production of medicines and supplements to strengthen the immunity system would see a sharp increase. Public transport could suffer, but demand for 2-wheelers and small cars could increase. The experimentation with online education at the level of schools and colleges should get a boost, resulting in advances in the general literacy level, skilling and training. Many e-learning modules are expected to flood the market. The opportunities that the digital world offers are immense and millions of young people will experiment with online education in vernacular medium, introducing digital books, and programmes that will open exciting vistas.

The construction sector has been under stress for quite some time. The stress could continue and the shortage of migrant labour, restrained finances, and the onset of monsoon could delay construction activities. The shortage of labour could negatively impact MSMEs, construction activities, and agriculture sector. To ensure that they actively join back production activities, the government could consider cutting the daily wage rate and the number of days under MGNREGA.

READ: Coronavirus and capitalism’s hour of crisis

There is a fear that restaurants could take time to revive. But the nature of business may change with people working from home demanding home delivery of food day and night. Air travel could suffer, but road and rail travel may flourish for movement of people and freight. Parcels, documents and goods could travel faster, by air, in the new circumstances. The hotel industry is expected to record a sluggish growth in occupancy, but experiments like holding day-time functions and business meetings may hasten the recovery.

The lockdown has resulted in some demand getting postponed like purchase of white goods and durables. Once the lockdown ends, this pent-up demand will find an outlet. The production of these goods could expand. The government should consider permitting a 6-day or even a 7-day week for businesses to compensate the loss of man-days during the lockout.

The global situation is critical which implies that India’s exports could suffer. But as the price of crude oil has nose-dived, the import bill will shrink and the current account deficit will be contained around 2.5% or even less than 2% of the GDP. Further, if exports do not pick up due to a possible global recession, there is enough demand in the hinterlands of India and therefore production should not suffer. With more people working from home and the way they commute changing, the new demand for textiles and fashion accessories may be affected. To address the demand from hinterlands, new opportunities should emerge for textiles and fashion. In any case, installed capacity need not be destroyed with new markets emerging.

READ: Narendra Modi government should withdraw suspension of MPLADS

The government is expected to come up with more stimulus in addition to the already declared ones. So, consumption losses due to the lockdown would be compensated by an increase in government expenditure. The slowdown in recovery would be reflected in tax collections and hence deficit is bound to expand, as is the case of many countries, both advanced and emerging. In fact, the Union government should consider suspending the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management Act for both the Centre and state governments. The Government should aggressively support businesses and individuals as done in most countries where stimulus packages are of the size of 10% of the GDP. On specifics, the government, as expected, would need to support tourism, travel, aviation and hospitality sectors. As MSMEs in these sectors would need immediate support for revival, an MSME Survival Fund may be constituted. As pandemic impacted production, revival through pump-priming in initial stages could mitigate the ill-effects of disruption. Once, the production is back on track, tax revenues would flow smoothly again. The demand for products from the unorganised sector may have been affected badly. So, the basic needs of the unorganised sector, especially daily wage labour, need to be met throughout the lockdown with adequate food supplies. Once, the production process starts again, and hopefully with permission to work all the days of the week, business in the unorganised sector could boom.

The crisis has exposed the hazards of the Chinese monopoly over global manufacturing. Now global firms must be exploring alternative production bases to ensure business continuity. India will need to develop regions where global firms can set up base. To kick-start the economy and revive growth, the central and state governments could start developing such areas in anticipation of global demand that will generate employment and ensure steady flow of liquidity into the system.

READ: Revive social ties to survive Covid-19 reverse migration

Most businesses work for about 270 days a year. With one quarter of the year lost due to lockdown, there are still about 270 days left in the year to recover and recoup lost output and business, assuming that Government permits a 7-day week. Traditionally, the busy season when the economic activity starts peaking is from October. The Covid-19 shock has happened in the lean season of the economy and India Inc should be able to stage a smart recovery in output and profits.

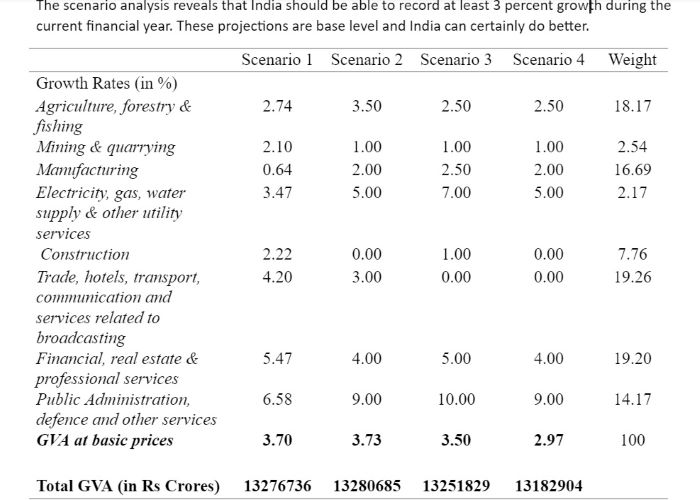

If the economy is managed well and support is offered for recovery, India can bounce back faster than previously thought. Here are the possible scenarios (see table) for the Indian economy.

Scenario 1 projects forward growth estimates of 2019 by shelving 25% of the growth assuming that 3 months are lost to COVID 19.

Scenario 2 assumes modest growth in manufacturing, while essential services such as electricity, gas and water unaffected during through lockdown. Construction is expected to register no growth.

Scenario 3 assumes modest growth in agriculture and zero growth in trade, hotels, transportation etc.

Scenario 4 is the worst-case scenario where there is modest growth across most sectors while no growth in construction, trade, hotels and transportation

(Dr Charan Singh is a Delhi-based economist and the chief executive of EGROW Foundation. Karan Bhasin’s support in preparing the table is thankfully acknowledged)

Dr Charan Sigh is a Delhi-based economist. He is the chief executive of EGROW Foundation, a Noida-based think tank, and former Non Executive Chairman of Punjab & Sind Bank. He has served as RBI Chair professor at the Indian Institute of Management, Bangalore.