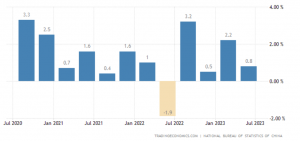

China’s economic problems have captured global attention, casting shadows both domestically and internationally. The impact of sluggish growth is being felt in the world’s second largest economy, with unemployment, labour unrest, and crashing property prices corroding household affluence. News of China’s official entry into deflation with a 0.3% dip in consumer prices last month has kindled apprehensions that the economy might descend into a downward spiral.

China has slipped into deflation at a time when other major economies are battling inflation. The Chinese economy has been witnessing a slow recovery from the slowdown triggered by the coronavirus pandemic and country wide lockdowns. The slow recovery of the Chinese economy is a major factor that affected the global economic recovery post Covid-19 outbreak.

READ | FTAs at risk: Harmonised system revisions complicate rules of origin

The stammering cadence of growth in Chinese economy, should it endure, will reverberate beyond its borders, just as numerous economies grapple with post-pandemic convalescence. Back in May, the International Monetary Fund forecast 5.2% growth for Chinese economy this year, which translates into a 35% contribution to global growth.

Chinese economy losing sheen

Recently, some investment banks had cut their GDP growth predictions for the year 2023. Significant structural obstacles, such as the looming burden of local government debt, the advancing march of an aging populace, and regulatory constraints encircling the private sector, have begun to press more heavily upon China’s economic prospects. Moreover, the fraying economic ties with the United States, evident in fresh restrictions for US investment in Chinese technological enterprises, portend additional squalls on the international horizon.

China consumer price inflation

With all these red flags unfurling, China is now at the crossroads, demanding more than mere incremental adjustments and necessitating an audacious blend of reforms and stimulants. The aftermath of a July politburo gathering, which sounded the clarion call for “amplifying countercyclical measures,” has thus far been characterised by rhetoric rather than tangible action. Beijing must squarely address the two major obstacles. First, there is the shadow cast by the impending defaults by local governments that have amassed an intimidating $9.3 trillion in debt through a myriad of occasionally obscure financing conduits. Second, an overarching psychological gloom has restrained households from unshackling their purse strings.

China GDP growth rate

To resuscitate local government finances — thereby infusing verve into localised investment — there exists a compelling case for Beijing to endorse a practice that has stealthily germinated in certain pockets of the nation, asserts Gavekal Dragonomics, a distinguished research firm. The clarion call should be for state-owned financial institutions to reimagine substantial slices of local government debt through elongating maturities and reducing interest rates. The deflationary currents swirling about China should lend wind to the sails of this endeavour.

However, such intervention should not be proffered sans a price. Local governments must be cajoled into revealing accurate balance sheets of their portfolios, encapsulating investments orchestrated through local government financing mechanisms, including those ventures that have soured. Without lucid bookkeeping, transition to the subsequent phase of local government fiscal rehabilitation — a sweeping disposal of underperforming assets, perhaps with suitable adjustments — to state and private enterprises, will remain an arduous proposition.

Expectedly, Beijing might resist treading this path, for despite its rhetorical backing of private enterprise, the Xi Jinping-led party-state recoils from granting entrepreneurs access to “state assets.” Yet, if this resistance remains untempered, China might find itself wrestling perpetually with one of its most entrenched economic conundrums.

The other front demands a campaign to mitigate the psychological despondency that shrouds Chinese economy. Major cities ought to explore measures to, at the very least, stabilise the property market; cities like Beijing, Shenzhen, and Guangzhou have already hinted at unspecified strategies in this realm. Initiating a reduction in mortgage interest rates, down payment ratios, and sundry other restrictions could constitute a propitious overture. If the descent of property prices can be arrested, households could find solace in the preservation of their principal wellspring of wealth.

A resurgence in sentiment might then kindle a more robust consumer resurgence, birthing a virtuous cycle. Conversely, failure to embark on substantial measures now to invigorate the economy could cast a pall over the already delicate confidence, risking a hastened plunge into the throes of deflationary spiral.

Impact of China’s problems on India

Should investments in the Chinese economic apparatus decelerate, spurred by the deepening cadence of their economy and the advent of deflation, India could conceivably ascend to the mantle of the developed economies’ manufacturing epicentre. This is a trajectory that the advanced nations appear to be nudging toward, in an endeavour to rupture the vice-like grip China has exerted over the manufacturing domain. For India, an acceleration of economic reforms might well catalyse its transformation into the subsequent manufacturing hotspot.

China is one of India’s largest importers of iron ore, picking up nearly 70% of its requirements from the South Asian neighbour. Ergo, a slackening Chinese economy could precipitate a diminution in imports, spelling potential adversity for the Indian economy. China’s flagging import and export metrics have already sparked queries about its post-pandemic convalescence.

China’s protracted dalliance with deflation could yield an unforeseen boon — the taming of inflationary tempests in other quarters of the globe, including the United Kingdom. China’s prominence as a producer of commodities means that markdowns in the prices of its manufactured wares could inadvertently impinge on employment dynamics and investment strategies for various enterprises.

Hence, even though the initial allure of plummeting prices might bedazzle consumers, a perilous cycle of diminishing economic activity could ensue. The abatement in demand, perpetuated by an enduring spiral of falling prices, could curtail production rates, attenuate corporate revenues, and escalate unemployment rates, thereby further eviscerating consumer spending.

Anil Nair is Founder and Editor, Policy Circle.