By Parmod Kumar

Farmers protest: The possibility of an agreement between the Narendra Modi government and the protesting farmers appears to be dim with both sides sticking to their positions in the seven rounds of talks so far. While the sides agree that Indian farmers are always at the mercy of the vagaries of the market and government policies, they disagree on the solutions to set farmers free. The three controversial Acts that attracted the farmers’ ire were brought in to strengthen contract farming. These Acts created controversy and farmers are sitting on a dharna against them. This paper seeks to explain the key determinants that drive contractual/ lease relationships through examples of various existing arrangements in the country. It is based on the premise that contract farming/ leasing can be an attractive option to policy makers keen on integrating the poor into an industrialised sector by helping them access the gains from trade.

Contract farming is a system in which production and supply of agricultural output are done under forward contracts. The essence of such contracts are commitments made by the farmers/ producers to provide an agricultural commodity of specific quality at a time and a price in quantity required by the buyers. In early 1990s, tomato and chillies were brought under contract farming, which expanded later into multiple products. Most recently contracting in exotic vegetables such as baby corn, bell peppers, Jalapeños and gherkins have started. This paper analyses contract farming in the broader framework of existing land and lease market system.

READ I Farmers protest: Market-friendly options for ensuring MSP

Farmers protest: Survey tells a different story

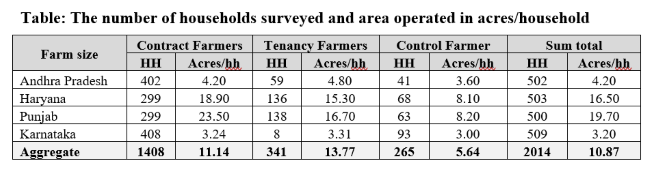

The findings are primarily based on a primary survey of 2014 farmers and 384 labourers from Punjab and Haryana in the north and Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh and Telangana in the south. These five states have vibrant operation of contract farming in India. The issue is relevant to market reform and land reform in the country. If contract farming can create new markets, fetch higher income for farmers and link small farmers to the modern food supply chain, then market reforms and land reforms to promote contract farming can be justified. If not, then policy makers should divert resources to other agricultural development policies.

Out of total 2014 households surveyed, 1408, or almost 70 per cent, were engaged in contract farming. All farmers had more than four years of experience with contract farming. Only 20% of the area cultivated by contract farmers was under contract, while the rest 80% was under non-contract crops. The survey revealed that contract was mostly oral except in Punjab where a majority of the farmers had written contracts. According to farmers, the necessary requirements for farmers entering into contract farming included assured irrigation, labour availability and reasonable size of holdings.

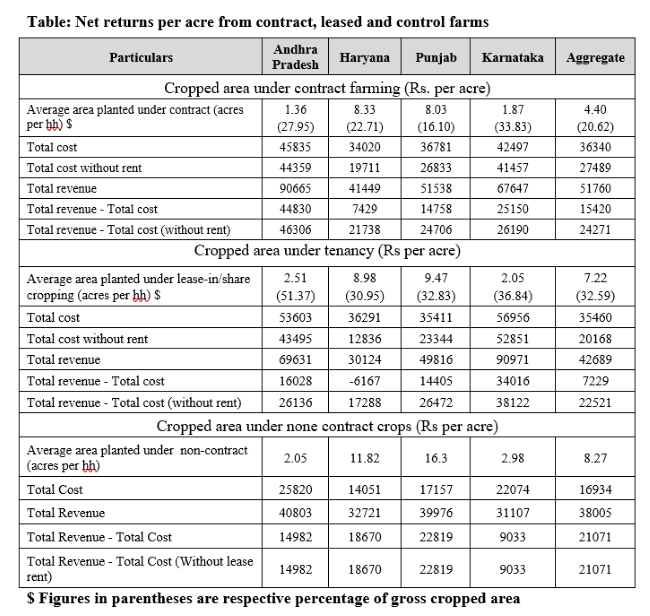

All the selected farmers indicated that the contracted produce was being procured. Only a handful of farmers said that a small quantity of produce was rejected. Similarly, breach of contract by the farmers was also almost negligible. Assured income, superior price based on quality and hassle-free marketing are the main advantages of contract farming, says farmers. A majority of contract farmers expressed their satisfaction with the arrangement. Comparing all contract crops, leased crops and control crops, on average, value of crop output per acre was the highest in the case of contract farming crops at Rs 52,000, followed by leased-in crops Rs 43,000 and the least was control crops Rs 38,000.

READ I Farmers protest: Holistic approach to farming key to ending agrarian distress

The value of output per cropped area under contract farming was the highest Rs 91,000 in Andhra Pradesh (including Telangana) followed by Karnataka Rs 68,000, and Punjab Rs 51,500 while the lowest was in Haryana at Rs 41,000 per acre. The two southern states were growing high value commodities such as gherkins, baby corn, jalapeno and green chillies under contract farming. In comparison, cereal crops like paddy and wheat were grown in Haryana and wheat and potato were grown in Punjab. Except potato, most of the other crops grown in these two states fetched low returns. Thus, diversifying cropping pattern towards high value crops like fruits, vegetables and animal products and paying more attention towards changing consumer pattern can help achieve the target of doubling farmers’ income in a set time period. The role of contract farming in helping farmers adopting such a cropping pattern and disseminating information and technical know-how is highlighted by the survey results.

The survey was carried out in Punjab and Haryana by the Sirtazi Support Foundation, Lucknow and in Karnataka, Andhra and Telangana by the Livelihoods and Natural Resource Management Institute (LNRMI) Hyderabad.

Better returns, more jobs

Employment creation was high among vegetable and high value crops and those crops for which value addition was done under contract farming compared with traditional cereal crops. Therefore, contract farming should be preferred for bringing in innovations in cropping pattern towards high value commodities, which farmers do not opt due to the lack of technical know-how, non-avilability of seeds / technology and the absence of a defined product market. All these issues can easily be addressed by the contracting firms. The Indian rural economic structure is witnessing changes and to sustain an agrarian economy that ensures food and nutrition security, raw material for its expanding industrial base, surpluses for exports, and an equitable rewarding system for the farming community, commitment driven contract farming and leasing are viable alternatives.

Unlike the earlier unhealthy relationship existed between the landlord and tenant, with the latter having no say in the terms of tenancy, the relationship has evolved into a partnership. Another emerging factor has been that all land holding categories of farmers from small to medium and large are also leasing in/out land to adequately and efficiently use their technical inputs and optimal utilization of capital resources. In addition, occupancy tenancy has been replaced by tenancy at will for a fixed period of time and rentals are paid in cash annually. In addition, consolidation of farmers through farmer producer organisations (FPOs), co-operatives and self-help groups can enhance firm-farm coordination and balance bargaining power between the contracting parties that has been a concern for most farmers.

READ I Farm Bills 2020: Death warrant to mandis, end of small farms

Summing up the observations on agricultural labourers, the number of man days generated in contract farm was higher than non-contract farms. There was no significant increase in the number of man days for female workers after the introduction of contract farming. The contract wage worker earned Rs 75,000 per year and non-contract wage worker earned Rs 50,000 per year. Contract wage workers spent Rs 34,000 per year on non-consumption items whereas non-contract group wage workers spent Rs 22,000 per annum. Area of operation of contract farms was found closer to village and city compared to non-contract farms. In Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh contract was signed between labourers and contracting farmers, but in Punjab, only 5.26 per cent of the labour respondents said that they signed contracts with the farmer or agency. None of the labour respondents reported signing of contracts in Haryana. The average duration of working in the farms found to be 11 hrs and 9.2 hrs in contract and non-contract farms, respectively.

The study shows positive income effects are a precondition for farmers to give up part of their autonomy in marketing, production and quality control. Assured income was the primary reason why farmers participated in contract farming. Hassle-free guaranteed marketing was also a beneficial attribute that induced farmers to enter into contracts. Employment creation was also high among vegetable and high-value crops and those crops for which value addition was done under contract farming, as compared to traditional cereal crops. A small proportion of farmers also considered that via contracts/leases they have access to new production knowledge, inputs and upgraded technical support that small and marginal farmers were unable to acquire. Diversification of cropping pattern towards high value crops, for which demand has been rising at a fast pace is another reason for farmer tilting towards contracts.

READ I Why Narendra Modi govt must address farmers’ fears

The issues that the farmers found disadvantageous were problems of rent fixing that might have been related to the issue of power imbalances. The study also revealed that a majority of the arrangements were short-term lease/contracts resulting in uncertainty in the year following the expiry of contract period. Also, both firms and farmers face risks — for example, farmers may side-sell products after having received the services from the firm due to better market prices at the time of honouring the contract. Short-term contracts have also resulted in overexploitation of leased land especially loss of soil quality and excessive use of groundwater, resulting in low environmental footprints, while tenants are unable to make long-term investments and input subsidies, crop insurance and crop loss compensation were transferred to land owners’ account were among other demerits of contract farming.

Institutional intervention can induce agribusiness firms to offer more attractive and equitable contracts through a negotiation process between the parties. The most effective being contractual arrangements that would include price premiums at the onset. Further, the study shows that large holdings earn high profitability and better net returns on account of economies of scale. It also highlighted the need to attract more small and marginal farmers via consolidation of small/marginal farmers to boost economies of scale. Farmer producer organisations and producer companies can provide favorable returns from contract farming given their better bargaining power, compared with individual marginal and small farmers.

(Dr Parmod Kumar is professor and dean, research, Institute for Social and Economic Change, Bangalore. Views expressed in this article are personal.)