When you talk to financial market participants, a certain short-sightedness can be observed. This short-sightedness is really at the core of where we are right now. When we discuss the recession and look at the market pricings, there’s a certain sense of complacency that after the recession and a correction, we will go back to where we were in pre-Covid days. In the US and EU, inflation is coming back to the target range quickly.

This complacency prompted me to think weather we do actually really go back to where we started or is there something fundamentally different. Before we talk about the next cycle, it is helpful to have an understanding on where we are today. If you define a generation as 30 years, we really are witnessing a once-in-a-generation increase in inflation. We haven’t seen the kind of inflation numbers in developed markets in the last 40 years which led to a once-in-a-generation level of interest rates.

The interest rate hikes come from the view that demand is the source of the phenomenal rise in inflation, particularly in the US. The monetary tightening is designed to reduce demand even at the cost of a global recession. If you look at a global mix of assets, you are actually seeing one of the largest sell-offs in the last 100 years.

READ I Old pension scheme promises hit PFRDA hurdle

Global economy post recession

We are in a unique situation right now. There are five important trends that will shape the next cycle. The first one is that the inflation is likely to be more persistent and we are likely to face higher than target inflation going forward. The second one is that the era will see higher geopolitical risks from great power rivalries. The third is that there’s a lot more demand on the state that governments will play a much bigger role. The fourth point is that the nature of globalisation is changing and then the final one — the trend growth in China has fallen tremendously and it will continue to do so.

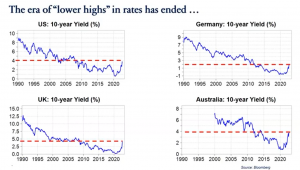

Let us see how things have changed since the beginning of last year. We have lived through a period where the high interest rate in one particular cycle has always been lower than the high interest rates in the previous cycle. Now that dynamics has changed. From 1990, the peak rate in every cycle kept declining. Now for the first time at least in the last 30 years in this series we have actually gone higher than the last cycle. This has happened in the US and Germany. Interest rates have broken out of that trend in the UK and Australia too. So, will this prevail?

There are two schools of thought on why inflation was very weak after the financial crisis. The first is Larry Summers theory about secular stagnation – a persistent low demand. The other you know is Kenneth Saul Rogoff theory that we were experiencing a typical recovery from a financial crisis. It’s a period of deleveraging and you had savings rates elevated and investment rates kind of constrained.

READ I India’s housing finance companies struggle to stay afloat

The difference in the current cycle is that that pressure for deleveraging is no longer there. If you look at financial institutions, a lot of the balance sheets are actually in much better shape and there is no pressure for deleveraging like in the last cycle. So, there can be a potential scope for demand being higher than it was in the post-global financial crisis period. The second difference is the energy transition. The amount of capital expenditure needed globally to get to net zero is about $4 trillion per year for the next two decades which is 4% of GDP.

The first point says maybe savings rate need not be so high as it was in the deleveraging phase. But you are also seeing new investment potential picking up. If the world is serious about getting to net zero, the price of carbon has to be higher. This brings another inflationary force into the system. The third point is that the global supply chains have already started to shift away from ‘just in time’ to ‘just in case’, focusing on resilience rather than cost minimisation.

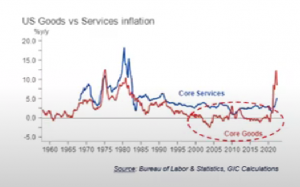

The chart above shows the breakdown of US inflation into goods inflation and services inflation. The experience over the last 20 years has been that core goods in the US saw an inflation rate of about zero, if not slightly negative. So, you’ve had a big deflationary impact coming from core goods. If you look at the timing, it coincides with China’s entry into the WTO. The rate of inflation on core goods is closer to that in core services which has been about 3%. That fundamentally changes the way average inflation rates are likely to be. So, that’s the big point number one — inflation is likely to be higher.

The second point is about the great power rivalry between the US and China. There is a bit too much focus on the potential for some sort of invasion on Taiwan. Nobody knows what’s going to happen there, but there are aspects of this new geopolitical paradigm that are already impacting the way companies and investors operate even today. There are much greater barriers to cross-border investment. The US regulations on CPS have been tightened over the past few years.

There have been foreign investment restrictions just introduced in Australia and the UK. It is much harder now for free movement of capital as it was in the past. The definition of national security has fundamentally shifted. Some industries face greater scrutiny for foreign investment and governments have increased data protection. The third point is that there is a bigger push among countries to achieve self-sufficiency. For example, you will find a larger presence of state players in different Industries.

The third point is about governments. One interesting thing is that a lot of people draw parallels with the current environment to the 1970s. The interesting thing is that after the 1970s, the big push was for smaller government. The Reagan-Thatcher revolution was a push for smaller government, privatization etc. Right now, the push across the board is for bigger government. There’s a lot of demand for government intervention to help insulate the public from rising costs, greater push for higher defence spending, and to address issues related to inequality.

The fourth point is about the changing nature of globalisation. The term de-globalisation is a bit of an exaggeration. Globalisation will always be there but the nature is changing. You can’t paint all countries by the same brush on this. This idea is about sectors where governments would like to have some kind of strategic autonomy, where they would like to have supply chains within their own borders.

The last point is about the deceleration in growth in China. There is a structural phenomenon that will last for a while. If you just look at the first decade of the century, China was growing at an average annual growth rate of 10%. In the next 10 years, the growth rate was 7.5%. This decade, the trend growth rate would be close to 4%. The biggest factor here is the demographic profile of China where working age population is shrinking. You are looking at an economy where the biggest driver of growth has to be productivity and productivity growth is actually falling.

So those are the five factors that will shape the next cycle. The implications of these five factors will go beyond the current cycle. We have gotten used to a period of interest rates trending lower, boosting asset valuations. I think that is behind us. Over the last 10 years, we have gotten so used to central banks trying to reach their inflation targets from below. But we are likely to enter a period where central banks are likely to be attempting to reach the inflation target from above and that is very different. It would result in much higher macro volatility and potentially shorter cycles.

The real assets – infrastructure, real estate, commodities — are likely to do well in the new environment. Going back to globalisation, the phrase emerging markets becomes less and less useful. We have to think about individual countries and not treat them as a plot. This notion of big government runs the risk. The next big crisis would be a big public debt crisis in a major economy.

(Prakash Kannan is Chief Economist and head of portfolio at GIC, an investment arm of Singapore government. This article is an edited version of Dr Kannan’s talk at an online event organised by EGROW Foundation, a Noida-based think tank.)