Global fiscal coordination can benefit individual nations and the world economy in several ways. Some of the proven benefits of fiscal coordination are improved economic stability by better handling of shocks, higher efficiency in trade and financial flows, and better policy outcomes. Fiscal cooperation can also lead to enhanced international cooperation between nations and smoother diplomatic ties.

Despite these obvious benefits, political pressures and difficulty in arriving at consensus act as hurdles to close fiscal coordination between nations. Also, several countries show a hesitation in compromising with their sovereign right over policy making. EGROW Foundation organised an online discussion on the topic with some of the world’s foremost experts presented their views on the subject. Edited excerpts:

Global fiscal coordination and govt debt

Barry Julian Eichengreen, George C. Pardee and Helen N. Pardee Professor of Economics and Political Science, University of California, Berkeley.

It is evident from the high level of public debt in general government data that the global debt problem is challenging. In the past, there was a gradual progress towards fiscal consolidation as the debt-to-GDP ratio declined before the global financial crisis. This trend has reversed significantly after the Covid-19 pandemic, resulting in a substantial increase in debts. Temporary fall in debt ratios in 2021-22 due to inflation is more worrisome.

Low-income countries such as India have also experienced an increase in debt ratios compared with pre-global financial crisis levels. The composition of debt has shifted with the foreign official sector accounting for a smaller share of total debt, while private creditors, domestic non-bank investors, and foreign non-bank investors have become more prominent. This is more evident in the case of lower middle-income countries.

READ I Monetary policy coordination among central banks desirable during crises

High-income countries are likely to face prolonged higher debts. Projections of reducing debts through substantial primary surpluses over extended periods may not be practical. The interest rate differential may be less favourable for high-income countries in the future, and headwinds to growth may persist. Inflation is not a sustainable strategy for reducing high debt, as investors will demand higher real returns. Inflation may only serve as a temporary solution.

Efforts were made in 2021-22 to address the debt distress faced by low-income countries, but the markets are still likely to react to the same problems. Thus, there is a need for the International Monetary Fund’s recommendation to restructure the debts of three dozen low-income countries that are facing severe debt distress. There has been little progress in this direction in recent years. However, a potential positive development may be where China does not insist on the World Bank and IMF taking losses on their loans.

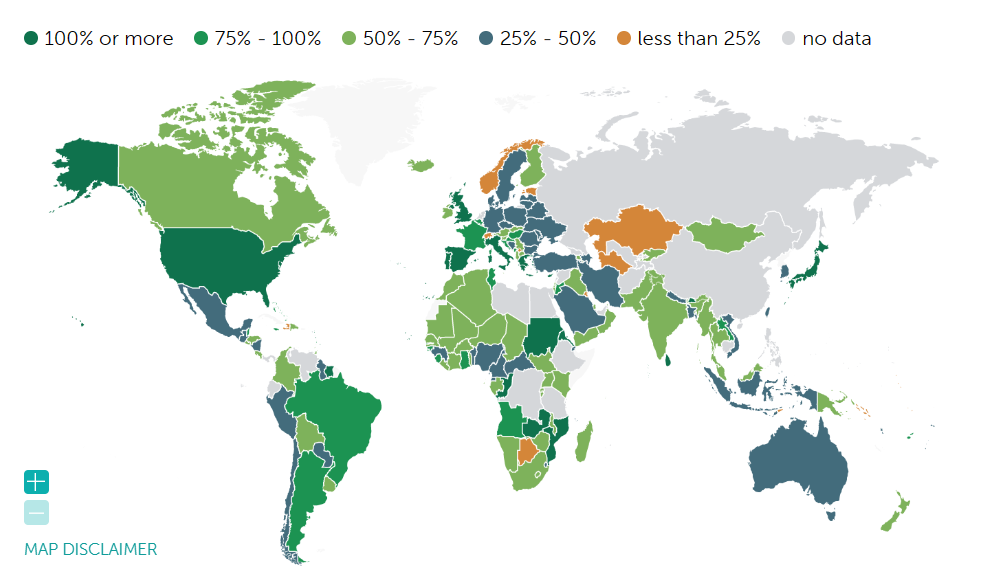

Government debt as % of GDP

It has been observed that primary budget surpluses remain important in retiring debt. For example, Great Britain post the French and Napoleonic War maintained primary surpluses for nine decades and significantly reduced its debt-to-GDP ratio. Thus, the IMF’s recommendation to run primary surpluses as a way to bring debt levels down to more tolerable levels must be more prudently followed to maintain proper fiscal discipline.

Certain historical instances of countries implementing budget surpluses, low taxes, and limited government, and how these actions were shaped by unique political conditions may be provided. British leaders acknowledged the importance of rebuilding their borrowing capacity for potential future conflicts advocated for prudent financial policies. In the United States, creditor influence and low military spending needs led to budget surpluses after the Civil War.

READ I Opportunities and challenges as India becomes the most populous country

France also reduced its debt-to-GDP ratio through primary surpluses following the Franco-Prussian War. However, these circumstances are not currently prevalent in advanced countries in the 21st century. There have been limited cases of countries running significant primary surpluses e.g., Norway saving oil revenues for future generations and Belgium running on surpluses to meet euro convergence criteria.

Singapore, despite facing economic volatility and geopolitical challenges, was able to achieve budget surpluses for a prolonged period due to its strong technocratic government. However, this is not the case for most other countries, as persistent budget surpluses are uncommon.

Further, it is observed that although the Covid-19 pandemic has accelerated digitisation and artificial intelligence, there is no evidence of increased productivity leading to faster economic growth. The faster productivity growth may only be realised post 2035 or 2040 with the current generation of artificial intelligence and related innovations.

Often inflating away debt is considered as a solution to heavy debt burdens. Some argue that inflation can help reduce debt, while some found that while inflation may initially lower the real interest rate on debt over short periods, this effect diminishes and may even reverse itself over a longer period of 15 years. Thus, inflation does not remain a viable solution to the debt burden.

The potential for higher real interest rates in the near future due to the heavier debt burden that needs to be financed by investors remains a point of concern. Further, it does not seem that the current political situation in most countries is conducive to run large budget surpluses for extended periods of time. This recommendation can be relevant to developed countries where heavy debt burdens can lead to financial fragility and limited fiscal flexibility, as well as low-income countries where debt restructuring may be necessary.

M Govinda Rao

Former member of Fourteenth Finance Commission, Former Director, National Institute of Public Finance and Policy, New Delhi.

The aftermath of the pandemic recovery has witnessed a notable upsurge in government deficit and debt with a considerable number of low-income and emerging market economies at heightened risk of debt distress. Despite a reduction in global debt from 100% of the GDP to approximately 92% owing to recovery endeavors, conflicting pressures have arisen. On one hand, there is a drive to augment public spending in order to revive economic growth and address various concerns such as climate change and global price increases.

On the other hand, fiscal consolidation is essential to tackle the distressed economic scenario. Many countries find themselves grappling with the predicament of striking a balance between fiscal consolidation and the imperative for public spending. The IMF’s review indicates that success rate of fiscal consolidation has been subpar in numerous low-income countries, even in the absence of additional strain from the pandemic.

Countries with low incomes conduct two tests to assess fiscal consolidation success. The first test has a success rate of one in five episodes based on targets set, but increases to two out of three episodes when considering threshold improvement in outcomes. Literature review suggests success rates ranging from 38% to 50% in the first category and 21% to 65% in the second category. Many countries struggle to adhere to the rules of a rule-based fiscal policy due to political or other reasons.

The IMF found that G20 countries with stronger fiscal institutions have desirable outcomes including stronger fiscal adjustments, quicker fiscal adjustment plans, protection of public investment, better plan implementation, and improved response to external shocks. A strong track record of fiscal management improves the likelihood of successful consolidation by establishing a culture of credible commitment to reform and sound programme design.

To achieve higher success rates, fiscal consolidation should be supported by a credible medium-term fiscal framework, strong fiscal institutions, and sound design. Implementation should include fiscal rules, transparency, accountability, and efficient public finance management systems. Countries with independent fiscal institutions such as fiscal councils tend to perform better, according to IMF studies. Structural reforms should be integrated into fiscal consolidation programmes, and capacity development programs should be in place to strengthen overall fiscal management.

In India, a formal rule-based fiscal policy was established with the FRBM Act in 2003, but Parliament has not been proactive in fixing borrowing as required by Article 292 of the Constitution. Significant blow to fiscal consolidation happened due to decisions made in 2008-2009, such as loan waivers for farmers, pay commission recommendations, and the expansion of rural employment guarantee, which resulted in an increase in revenue deficit and fiscal deficit.

Additionally, there are issues with capital expenditure, as many projects are experiencing cost overruns. The overall experience with rule-based policy in achieving fiscal consolidation in India is unsatisfactory.

In India and other countries there are common occurrence of incidents like rule suspensions, definition changes, lack of transparency and accountability, and failure to meet targets. Specific examples of these are foreign payments by the National NSSF, fertilizer subsidies facilitated by banks and LIC, disinvestment of public enterprises, and recommendations by Finance Commissions for adopting an accrual accounting system.

The impact of the pandemic on fiscal assessment, including economic contraction, fiscal measures for food security and health spending, decrease in revenues, increase in fiscal deficit and liabilities, and partial recovery in 2021-22 was unique in nature and never observed before. There is a need for implementing fiscal rules and establishing a modern public finance management system to strengthen the budgetary process and accrual accounting.

The importance of fiscal institutions in providing assurance and guidance through an independent assessment mechanism, specifically the fiscal council is the need of the hour. The significance of institutional reforms and the use of technology in achieving fiscal management objectives remains pivotal. There is a requirement for a fiscally responsive budget management act post-pandemic and the limited relevance of pre-pandemic targets.

There has been positive improvements in recent budgets in India, including transparency, realistic forecasts, and efforts to increase capital expenditures while upholding fiscal consolidation. Additionally, India should reduce the fiscal deficit to 3 percent. The proposal to lend to states for capital expenditure is a laudable approach. There has been a favourable development of increased tax collections, particularly in income tax and GST, and the potential of improved compliance for debt consolidation. Overall, there is a need for fiscal management reforms involving the three pillars and amending the FRBM Act accordingly.

Ashima Goyal

Member, Prime Minister’s Economic Advisory Council; Professor, Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research, Mumbai

After the global financial crisis, there was coordinated fiscal and monetary expansion worldwide. Fiscal stimulus is crucial as it spills over to other countries through trade, but there is an asymmetry in this — the US can print dollars to finance its fiscal deficit, while emerging markets face challenges such as rating downgrades, higher borrowing costs, and outflows.

The revenue deficit declined initially in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, but it has now risen again. Persistent borrowing over a long period can lead to the accumulation of debt and interest payments, which is why the revenue deficit continued to rise even when other deficits fell during the post-reform period.

A lesson from the global financial crisis was that the stimulus has not reversed, resulting in a prolonged period of high deficits, leading to slow growth due to double deficits and financial issues. However, in the pandemic times, there has been a sharp rise in deficits, but some improvements in budgetary practices have also been implemented. There has been an inflationary reduction in debt. Despite the reduction in deficits, Indian inflation has not been as high, indicating a positive trend for the future with a faster reversal time.

On the issue of global government debt and its impact on various countries, with a specific focus on India and the United States, it is seen that India’s debt has declined in recent years and is expected to remain stable until 2027 due to improved policies and the implementation of a strategy called balance coordination counter cyclical and reforms (BCCR). India’s past experience of volatile growth can be attributed to fluctuations in real interest rates. However, keeping them below growth rates can contribute to reducing debt.

Potential overreactions in fiscal and monetary policy during the pandemic have been justified on the basis of maintaining the dominance of the dollar by the United States. However, these abrupt increases in interest rates can result in volatility in capital flows and exchange rates, leading to decreased confidence in the dollar and exposing weaknesses in the country’s financial system. Thus, prudential regulation could be employed to mitigate these risks.

Further, there is a significant impact of monetary policy on the financial sector. During crises, simply maintaining high interest rates may not be sufficient, as pointed out by the IMF in recent spring meetings. Employing regulations in a prudent manner, not abrupt tightening, during crises is important as it may exacerbate the situation. Lack of proper regulation for small banks and non-bank financial sector in the US has resulted in the emergence of financial fault lines and potential spillovers.

The issue of rising interest rates and its implications on government debt in advanced economies remain a point of concern. The US government debt as a percent of GDP rose from 85% in 2005 to 140% during the pandemic. However, it is noted that the average debt servicing as a percentage of GDP actually declined to 1.5% during the pandemic due to low treasury yields and near-zero interest rates before the crisis.

Nevertheless, caution is urged in the light of past crises where the high interest rates during the period of high inflation led to the enactment of the Budget Enforcement Act in the US. This helped in reducing debt during the Clinton years through spending caps and a pay-as-you-go system for new schemes and the recent SVB crisis. Thus, for a country, the efficiency of a combination of effective monetary policy and fiscal conservatism is a major strategy to tackle government debt.

There is consensus that inflation and tightening measures will keep real interest rates low, but a point of concern is the negative impact on the dollar and potential challenges from payment innovations. Thus, there is a need for the US to avoid extreme monetary and fiscal policies, respect rules, and avoid unilateralism to maintain global stability.

Estimates by the IMF and World Bank that 15-60% of the LDCs are experiencing or approaching financial stress. The sovereign yields have increased, resulting in higher borrowing costs for highly indebted countries. The G20 common framework for debt reduction has not been effective with only three countries showing interest and deep debt restructuring being required for it to work.

They note that bilateral creditors like China and private creditors pose challenges in reaching agreements. China insisted on Bretton Woods institutions taking a haircut which is not legally binding, but has implications for other loans.

Some potential solutions include encouraging the Asian New Development Bank (NDB) to use its preferred creditor status to leverage capital more efficiently, extend more loans, and explore ways to make climate finance more generous for mitigation and adaptation efforts. The idea of reinsurance for catastrophe risk, using information from the IMF should be looked into to reduce the cost of insurance and thereby lower borrowing costs for emerging markets and low-income countries.

Rathin Roy

Managing Director, Overseas Development Institute; Former Director of NIPFP.

A number of theoretical frameworks has emerged in the fiscal/ monetary coordination between developed and emerging economies. This is due to the ending of certain assumptions underlying monetary and fiscal policies. The Bank of England has been unable to establish a clear link between interest rates and inflation, leading to questions about the efficacy of interest rates as a tool for managing inflation expectations.

the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has a somber outlook regarding the high levels of debt that countries will have to deal with for the foreseeable future. The challenges of managing the negative consequences of this debt, such as an aging economy, lack of investment, and political unwillingness to lower interest costs, are a matter of concern. Germany’s ability to maintain trade surpluses reflects pessimism.

The consequences of this reality are seen in the UK, France, Germany, Italy, and other countries, where fiscal constraints are evident in means-testing for school meals based on income levels. Providing free school meals to children in the UK earning more than one-fifth of the per capita income remains unaffordable in the UK, in contrast to India where school meals are not means-tested for those attending public schools.

The emerging economies have not been impacted as these economies are facing fiscal constraints, not due to excessive spending, but rather due to minimal spending and limited deficits. Monetary policy has proven ineffective in addressing the issue due to high inflation. The countries are considering increased productivity as a potential solution, but there is a growing demand for industrial policy instead of fiscal or monetary measures.

The war in Ukraine is a decision made by Europe, has resulted in high energy prices, which has jeopardised discussions on investing in climate-proofing the economy. The immediate concern is opening up coal mines which is difficult to reverse making the condition in Europe worse. Amidst, all these the US is also implementing extreme environmental acts and moving towards protectionism.

The emerging economies, such as India and Brazil, the growth ambitions are now scaled back. India has revised form double-digit growth estimates to 6 percent growth which remains sustainable. Fiscal management has improved, but public investment is increasing because consumption and private investment are not growing. Further, China’s dividend is not benefiting India, but rather countries like Mexico are gaining from the same.

Despite some unfinished business in terms of exports, India’s slightly has a higher level of debt but it is manageable with fiscal and monetary policy coordination. Brazil has also moderated its growth ambitions. Other emerging economies like Turkey and South Africa have faced challenges with macroeconomic policy too. Low-income countries have faced dramatic situations also.

IMF is becoming more radical with policies such as climate and gender policies. IMF’s recent call for a debt relief package for Africa was a bold policy indeed. However, with current lending practices in U.S. dollars, causes issues with currency depreciation and structural difficulties for African countries. Multilateral institutions like the Bretton Woods institutions should consider ramping up lending in domestic currency, which could benefit Africa. Further, countries like Pakistan and Sri Lanka due to their own policies are facing challenges too.

The challenges of poverty and climate change that have resurfaced in both advanced and emerging economies, focus on the need for macro fiscal and monetary coordination to address these challenges. A funding of a trillion of dollars, is a major concern, especially at the fiscal and monetary management level due to high debt numbers and domestic constraints.

The difficulties faced by rich and emerging countries in managing their finances and the repeated unserviceable debt issues in African countries are a matter of concern too. There is a need to rethink coordination approaches between countries and prioritize addressing challenges faced by rich countries.