The India-UK FTA: India has set a target to achieve $1 trillion in goods exports by 2030. The UK too, after becoming ‘a newly independent trading nation for the first time in nearly half a century’ with Brexit, has a trade strategy that champions free trade and fights protectionism. The UK government’s ambition is to become a truly global Britain and secure free trade agreements with countries that account for 80% of its trade in 2022. The first such agreement was an FTA with Japan. It has also applied for joining the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, which is one of the world’s largest free trade agreements, representing 13% of the global domestic product in 2018.

The Indian government has remodelled its trade agreement policy and aims at signing several FTAs by the end of 2022 with Australia, Israel, the EU, Canada, and the UK. India did not sign a single FTA since the NDA government took over because of concerns over the experience of various pacts signed during in the first decade of the century.

As part of the common strategy, Prime Ministers Boris Johnson and Narendra Modi launched the India-UK Enhanced Trade Partnership (ETP) on May 4, 2021, laying out the roadmap for concluding a UK-India Free Trade Agreement. The negotiations for this were launched in New Delhi on January 13. The FTA is expected to facilitate the doubling of bilateral trade between India and the United Kingdom by 2030.

READ I Covid-19 crisis: CSR must supplement govt’s grassroots transformation efforts

Trends in global trade

Global trade in goods has increased substantially since the turn of the century, rising from about $10 trillion in 2005 to more than $18.5 trillion in 2014. It witnessed a fall before rebounding to $18.8 trillion in 2019. Services trade increased even faster between 2005 and 2019 from around $2.5 trillion to $6 trillion. In the present context, it would be relevant to mention that while the value of trade in goods is almost equally shared between developing and developed countries, developed nations accounted for about two-thirds of trade in services in 2019.

India, an emerging economy, has recorded the fastest growth in global trade in services, from $285.56 billion in 2014 to $381.69 billion in 2018. The UK is also among the top global trading nations in services with a total export and import of $375 billion and $204 billion respectively. In FY 2021-22, India’s total merchandise trade and total services trade was at $936 billion and $394.33 billion respectively. Though in 2021-22, India reached a new milestone of $420 billion in the export of goods, India’s overall trade balance (merchandise and services) during the same period was (-)$91 billion.

Bilateral trade and investment

Here are some facts regarding India’s bilateral trade with the UK:

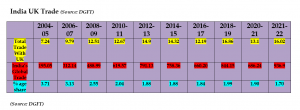

- India’s merchandise exports and imports with the UK during April 2021-January 2022 accounted for 2.52% and 1.19% of India’s global merchandise exports and imports respectively.

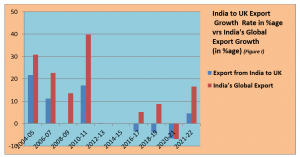

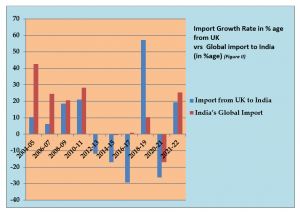

- The total merchandise trade with the UK is stagnant at around $14-16 billion since 2015-16.

- India’s trade with the UK increased by just 3.3% in 10 years to 2020-21, compared with the 10.8% overall growth in India’s global trade.

The bilateral trade in services between the two countries was worth $12.06 billion only with India having a trade surplus of $2.41 billion. - The stagnating value of exports over the last 10 years has raised concern, and the need to shift the focus from exporting low value-added products to high-value products is being felt.

India-UK investment flows

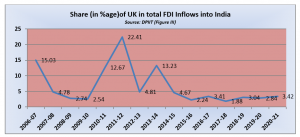

Close historical ties and common language have acted as a catalyst for greater bilateral investment flows between India and the UK. The UK’s foreign direct investment (FDI) holdings in India totalled $31.69 billion till December 2021, making the UK the sixth-largest investor with a 5.53% share. However, the investment flow from the UK has been declining since 2015 when it used to be the third-largest investor after Mauritius and Singapore. India continues to be one of the largest investors in the UK.

As shown in the figure above, not only has the percentage share of the UK in India’s annual global FDI inflows come down, the cumulative FDI inflows from the UK during 2015-20 were also much lesser at $6 billion compared to the $16.32 billion received during the preceding five years. Historical data reveals that UK companies predominantly prefer to invest in the US and EU countries compared with other regions.

Moreover, the uncertainty arising from Brexit has also affected the two-way investment flows between India and the UK. The proposed FTA with the UK will also cover investment as part of the comprehensive coverage and is expected to enhance the UK companies’ confidence in India’s investment climate. Incidentally, the UK was the first country with which India signed a bilateral investment treaty in 1994 which was allowed to be terminated in 2017.

Concerns of UK businesses

To address the issues raised by the businesses, a consultation between them and the government is considered critical to the FTA negotiations. On their part, the UK India Business Council (UKIBC) organised consultation roundtables in 2021, covering both SMEs and MNCs to understand their concerns. This report, titled ‘Road to a UK-India FTA’, mentioned the challenges in engaging in business with India, and their assessment of India’s business environment.

Despite these challenges, UK businesses accept the huge opportunities that India offers and want to be a part of the country’s growth journey. However, the following challenges as mentioned by UK businesses should be addressed as a priority for improving the business environment in India and enhancing the external engagement of the Indian economy:

EoDB issues: Most frequently cited obstacles are legal and regulatory barriers, taxation issues, corruption, and discrepancies between states on regulations, laws, and finding a suitable partner. Among the regulatory barriers, ensuring regulatory certainty and GST processes were mentioned as the most desirable reforms needed.

Self-Reliant India: While appreciating India’s aim to establish itself as a global manufacturing hub, UK businesses are concerned about protectionist measures, such as high tariffs on certain products for safeguarding domestic industry, which in fact, could deaccelerate India’s integration into global supply chains.

High tariffs: India’s tariffs rate is higher than the global average and is used not only to protect domestic industry but also as a tool to put pressure on foreign manufacturers/suppliers to invest and set up manufacturing capacity in India. The UK, in particular, is keen on tariff reduction on Scotch whisky and automotive products.

Data Transfer: The movement of non-personal data is vital for more flow of investments between the two countries. However, India does not have a law in place yet which puts limitations on this very critical aspect of the FTA and for some sort of an alignment of data regulations. The draft bill on data protection has strict provisions for data localization while the UK companies would be looking for easy access to data to get a better idea of the Indian market.

The UK has reached an agreement on data adequacy with the EU post-Brexit permitting personal data to flow freely between the UK and the EU. However, such an arrangement with India does not appear feasible given our strong stand on cross-border data flow. Early finalisation of the data protection law could help reach an alignment of data regulations paving the way for deeper engagement in research, innovation, and management of the digital supply chain.

Market share in the UK and challenges

Moving ahead, both sides must engage in constructive discussions and look at challenges with a positive outlook to overcome trade and investment issues during the FTA negotiations. Though the Indian export basket to the UK is quite diversified, the Indian negotiators need to pay serious attention to sectors such as textiles, leather, gems and jewellery, engineering goods, pharmaceutical products, and auto components for increasing our share in the UK market. The issues and prospects of expanding trade in some of such sectors are discussed hereunder:

Pharma products

The UK represents 2.3% of the global pharmaceutical market. In 2020, it imported $21 billion worth of pharmaceutical products from EU countries, which was 73% of all imports into the UK. Before Brexit, the imports from EU countries were higher at $26 billion. It is believed that the pharmaceutical imports from EU countries to the UK will be adversely affected by Brexit, thus creating a good opportunity for India to get a larger share in the UK market.

In 2020-21, India exported pharmaceutical products worth $618 million to the UK, representing just about 3.2% of its total pharma exports. However, penetrating a well-regulated pharma market like the UK will necessitate improving not only the quality and compliance levels in the Indian pharma sector, but also some other practical issues likely to be raised in FTA talks like the issue of price controls for patented pharmaceuticals and IPR enforcement in India which continues to be a concern for UK companies.

The Indian side has expressed hope that a mutual recognition agreement (MRA) between India and the UK could increase market access for Indian pharma products by eliminating duplicative testing and certification or inspection. However, experiences with such an arrangement between the US and EU do not support this view as MRAs have implementation issues, especially in highly regulated markets.

Instead, a fast-track approval process in the UK for generic pharma products already approved in the US or the EU could be a more convenient option. The UK will be looking for better market access in the Indian medical device market estimated at $10 billion and may seek the removal of tariffs under an FTA.

Readymade garments

India exports readymade garments of different types worth $20 billion annually out of which around $1.4 billion worth of garments is exported to the UK. In 2020, the UK imported apparel and other clothing accessories of the value of $20.5 billion with around 70% being sourced from non-EU countries.

The share of India in UK imports has shown a declining trend in the last three years. One of the reasons cited for India’s lagging is the absence of FTAs. However, an FTA alone is not the solution. For example, though China did not have an FTA with countries in North America or Europe and also faced higher tariffs than India or Bangladesh, it attracted many global brands which started sourcing from China due to its competitive rates.

Thus, besides FTA, it would also be helpful to study strategies adopted by high-end garment exporting countries like Hong Kong or Singapore to know their quality control strategies, marketing techniques, etc. Maintaining good growth in the export of garments requires a close watch on global fashion trends and the development of fabrics.

It would also be desirable to push the Indian garments industry towards manufacturing high-end apparel like sportswear, jackets, and jogging suits made of manmade fibre which command a global market share of around 75%. Moreover, this segment of the industry is generally less catered to by low labour cost economies like Bangladesh and African countries.

Leather and leather products

India exported leather and leather products including footwear worth $5.58 billion in 2019-20 with the UK having a share of around 11% of India’s global exports. The country has the most abundant cattle population in the world providing raw material for the industry which is also a highly employment-intensive industry providing jobs to more than 4 million people, mostly from the weaker sections of the society. However, despite a strong raw material base, India has a moderate share of 2.6% of global exports of leather goods.

The UK has a large market for these products and imported leather goods worth $3.84 billion in 2019. While watching the market trends in leather products, it is noticed that the leather footwear segment, though still the largest, has seen a declining demand trend in comparison to leather handbags and leather upholstery for luxury car applications. To capture a larger market share, the Indian leather products manufacturers must upgrade their facilities and manpower to align with the latest market demands of high value-added items and also need to comply with the environmental regulations standards which act as a non-tariff barrier in developed markets.

Movement of Indian professionals

India is seeking enhanced relaxations in regulations for Indian professionals to move and work in the UK, and the UK is facing shortages of workers in various services sectors which have become more critical post-Brexit. This is a sensitive issue and there is also political opposition in the UK over the issue of permitting professionals from other parts of the world to replace those from the EU.

It is quite likely that an early harvest trade deal may skip such sensitive issues. India needs to carefully weigh the pros and cons of such a quick ‘half deal’ covering only the trade of goods since the movement of professionals and increased investment along with technology transfer from the UK to India are no less critical than seeking greater market access for Indian pharmaceutical and agro-products in the UK.

India also needs to be careful and assertive about the scope and coverage of the agreement since the Indian government has recently undertaken several FDI reforms in the services sector, including liberalisation of retail and insurance services offering greater Mode 3 access in markets for foreign companies placing India in a better bargaining position.

India-UK FTA: Roadmap for long-term partnership

The Roadmap 2030 vision document issued by India and the UK in May 2021 expresses the commitment of both sides to elevate and strengthen the strategic relationship by synergising their respective strengths covering all aspects of our multi-faceted relations. The FTA proposed is an important component of the Enhanced Trade Partnership (ETP) and the vision document highlights the need for cooperation in removing trade and market access barriers. However, besides addressing specific challenges hindering bilateral trade and investment flows, two specific areas that require the close attention of the trade officials on the two sides are:

(i) The need to develop and expand cooperation in research and innovation including two-way mobility of researchers, mutual recognition of qualifications, and setting up joint centres for excellence in fields like climate change, automation in manufacturing, and renewable energy. The UK has a well-established innovation ecosystem consisting of a strong partnership between industry, academia, and research institutes which is reflected in the UK’s ranking of 4th in the Global Innovation Index (GII).

(ii) An early understanding of initiating consultations for signing a social security agreement between the two nations to ensure social and other benefits to the individual moving across borders for employment. This is an important necessity as India has emerged as a leading investor with several big M&A deals in the UK in recent years.

Krishna Kumar Sinha is an industrial policy and FDI expert based in New Delhi. His last assignment was as an industrial adviser in the department of industrial policy and promotion, DIPP, currently known as DPIIT, under the ministry of commerce and industry of the government of India.