The year 2021 marks 30 years of liberalisation of the Indian economy, a turning point in India’s history. The efforts of successive governments since then have been focused on achieving inclusive growth and self-sufficiency. The year, however, began in the backdrop of the Covid-19 pandemic that affected all sectors of the economy. As the economy started showing signs of recovery, the second wave of Covid hit the country, pushing many states into lockdowns and making recovery even harder.

To counter the adverse impact of the pandemic, the Union government announced the Atmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyaan in 2020 with a comprehensive package of Rs 20 trillion and launched several stimuli and incentive schemes to revive growth in Indian economy. As industrial development and broader societal goals share a close relation, the government took several measures to promote domestic manufacturing as it helps people move out of informal jobs and subsistence farming.

READ I Revisit industrial policy to transform Indian economy

Quality norms for domestic industry

One of the measures widely used since 2017 is the mandatory standards set by the Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS). The new BIS Act 2016 makes it easier for the government to notify specified standards as mandatory, often called “quality control orders”. The objective of quality control orders is to formulate technical regulations such as safety and quality standards for products to curb their imports.

Over the years, there has been an increase in the number of technical regulations across several sectors. The introduction of the compulsory registration scheme (CRS) for electronic and IT products in 2012 is cited as crucial in the use of technical regulations.

In 2020 and 2021, the DPIIT issued mandatory quality control orders covering products such as sheet glass, float glass, safety glass, toys, domestic pressure cooker, domestic gas stoves, plain copier paper, plugs, sockets, prepayment meters, bicycles, retro reflective devices, sewing machines, electrodes, spun iron pipes, air conditioners, refrigerating appliances, press tool- punches, butterfly valves, steel tubes, aluminium foil, cables, and rubber hose for LPG.

As per the orders, the notified items cannot be produced, imported, traded, and stocked unless they bear the BIS mark. To comply with these requirements, all manufacturers and importers of relevant products listed in Appendix III to the ITC (HS) of exports and imports must obtain a BIS license for using the standards mark on their products.

READ I Electronics manufacturing: Some practical steps to make India a global hub

During the last two years, 19 such quality control orders were issued against altogether 14 orders in the preceding 13 years to enhance the quality of domestic manufacturing. Similar orders were also issued by other ministries for products of their administrative controls under BIS Act, Essential Commodities Act, or Food and Safety Act. The decision was in response to the demand from domestic manufacturers for restrictions on imports given rising imports from countries like China.

The adherence to set quality norms is expected to help in making local producers more competitive globally. At the same time, these orders act as non-tariff barriers for import, protecting domestic producers from global suppliers. For an economy of India’s size and increasing external engagement, it would be prudent to review if the measures announced are helping local producers in achieving competitiveness worldwide as well as in their domain areas. Also, the additional compliance burden on companies worsen the ease of doing business.

Let see the impact of technical regulations on the import of toys where the dependence on China was near complete. As per DGCIS statistics, the total import value of toys covered under ITC HS 4 digit classification 9503 reached $304 million in 2018-19, out of which $261 million is from China. After the order on toys issued in February 2020, the import value of toys under the said classification came down to $130 million and $12.6 million during 2020-21 and 2021-22 (April-October) respectively. However, the share of China remained very high at around 86%.

It would be interesting to see how local manufacturers, especially MSME units, take the advantage of the gap in domestic demand and supply positions following the reduction in imports. The technical barrier in the import of toys has given a good scope for upscaling local production and looks like a fit case for a Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme for toys which is presently not among the 13 sectors chosen under the scheme. Interestingly, the overall import-export scenario with China does not indicate a change in the trend so far.

In addition, the government is also using public procurement by giving preference to domestically produced goods and services as part of the Make in India campaign, and also placed several products under the restrictive list for import under the Foreign Trade policy, thus requiring import licence.

READ I Union Budget 2022 may sidestep two-pillar solution

FDI norms can propel economic growth

Capital shortage has been among the major problems faced by the Indian economy. To overcome the deficiency, India uses FDI policy reforms as a tool to attract investments in various sectors of the economy including manufacturing. This offers multinational companies (MNCs) opportunities to re-examine their existing supply chains and reduce dependence on China. The year 2020-21 saw some more policy announcements aimed at liberalising the FDI policy framework:

- The defence industry was further liberalised in September 2020 to permit FDI up to 74% under automatic route and beyond 74%.

- In June 2021, foreign investment in the insurance sector was opened up with an enhanced equity cap of 74%, raising it from 49%.

- 100% FDI was permitted under automatic route in exploration activities of oil and natural gas fields, infrastructure related to marketing of petroleum products and natural gas, and marketing of natural gas and petroleum products.

- The limit of foreign investment in public sector refineries was also raised to 49% from 26% without any condition relating to any disinvestment or dilution of domestic equity in the existing PSUs.

- Indian companies operating in the telecom services sector were allowed to have 100% foreign equity under automatic route subject to licensing and security conditions.

The result of structured reforms carried out over the last decade has been positive with annual inflows rising from $34.8 billion in 2010-11 to $ 81.9 billion in 2020-21, putting India among the top five recipients of FDI inflows in the world. During the first six months of the current FY, the FDI inflows were at an impressive $42.8 billion. Besides recent reforms in FDI policy, improved ease of doing business, surging cross-border M&As, factors like low wage rate, robust banking system, and large market have been effective in attracting investments.

READ I Public health: Profit motive, state inaction dictate outcomes

Substantial growth in investment flows into India is considered creditable at a time when global FDI inflows have been badly hit by Covid-19, declining to $1 trillion in 2020-21 from $1.5 trillion a year ago. It is ,however, noted that despite sizeable growth in FDI inflows in recent years, India’s GDP growth which boomed in the years till 2016 has tapered off. Some features observed in the pattern of FDI inflows to India which underline the need for tweaking policy reforms are given below:

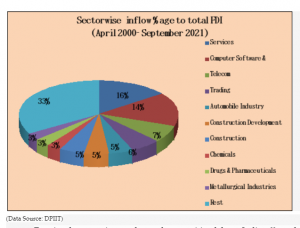

- Services sectors like financial banking, insurance, IT, telecom, trading and construction collected a bulk share of 68% of FDI received since April 2000. The rest amount of the FDI was shared among sectors like manufacturing, infrastructure, mining, etc.

- Sectors having huge potential of employment, requiring closely guarded technology, or having large imported inputs dependence like food processing, machine tools, electronics hardware, industrial machinery, textiles and medical appliances are not among the top recipients of investment.

- FDI from Japan, Germany, France, or South Korea remained static or declined. About 85% of total FDI inflows during the 24 months beginning in October 2019 were grabbed by Maharashtra, Gujarat, Karnataka, and Delhi. The next six states in that order, namely Tamil Nadu, Haryana, Telangana, Jharkhand, West Bengal, and Punjab had another 13% of the total FDI inflows, leaving the balance 2% for the rest. The huge gap in investors’ confidence across regions in the country needs to be analysed to check the ground-level reality of ease of doing business.

Despite the attractive market and competitive labour India offers, the large MNCs do not seem to be excited about making a long-term capital investment in India like those in a greenfield manufacturing plant or infrastructure creation. Domestic private investment has also not kept pace with expectations as they remain cautious to create new capacity for lack of demand. The recent exit of Ford Motors also suggests the same. A survey conducted by FICCI revealed that the overall capacity utilisation in manufacturing was at 72 % in the Q2 of the current FY.

The recently announced vehicle scrap policy is an important step for creating demand in the automobile sector. The PLI scheme is another right initiative and could help upscale local production. However, the government needs to look at other measures aimed at reducing raw materials cost and credit and logistics cost as impetus as well as EoDB measures like reducing compliance burden at the state level, avoiding frequent changes in the policy framework, and better coordination between different regulators to attract investment.

Foreign trade policy

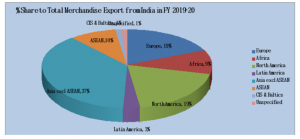

To address the problems of balance of payments, India needs to produce import substitute products or go for export promotion looking for new markets which need to be aided by a competitive and efficient manufacturing sector. Sustained efforts to create a manufacturing base and export promotion strategies by government agencies have resulted in an increase of India’s share in global merchandise exports from 1.62% in 2015 to 1.71 % in 2019. However, the trade deficit during the same period also increased from $126 billion to $155 billion.

In 2021, there are signs of recovery with exports reaching $323 billion in the first 10 months of the calendar year, raising hope of touching the $400 billion mark. The corresponding import figure for the first 10 months was at $462 billion and is estimated to reach $570 billion in the calendar year 2021. The current trends in export and import suggest a likely trade deficit of $170 billion in FY21-22. The current import-export scenario with China, India’s largest trade partner in 2020-21, does not indicate any major change in the trend witnessed in recent years so far.

Imports from China in the first seven months of the current FY were at $51 billion, thus signalling the annual import from China reaching the figure of $90 billion in FY21-22, the highest ever. Exports to China may reach $25 billion, also the highest so far, thereby causing a trade deficit of around $65 billion with China, almost 40% of India’s overall trade deficit expected during the current financial year.

While it could be early days to evaluate the impact of the PLI scheme and other incentives rolled out the current trends in external trade call for the need of overhauling our manufacturing ecosystem with a comprehensive reform rather than a selective approach in sectors.

A trade surplus contributes directly to economic gains like inclusive growth and in realizing other developmental objectives. The new Foreign Trade Policy expected to be announced in early 2022 would need to incorporate components to address challenges of increasing trade deficit, uncertainties arising from the pandemic-hit world, and also the arrival of e-commerce and digitisation on the trade mechanism and to ensure that the benefits of such digital platforms reach MSME units.

A re-look on the export basket is also called for in the light of changing consumer trends and emerging trade regimes post- COP26. Lastly, it must not be left aside that healthy growth in exports cannot be fully realized without a sound industrial and investment policy.

Foreign trade agreements

Bilateral, regional, and multilateral trade agreements have become strong tools globally for achieving market access and other economic objectives. After the initial hesitation, India is now a party to several regional trade agreements (RTAs) and preferential trade agreements (PTAs), with neighbouring countries and East Asian countries.

In addition, it has negotiated RTAs with several Latin American countries. After India’s last-minute withdrawal from RCEP, India is aiming to conclude separate investment and trade deals with the UK, Australia, Israel, and the EU, a welcome move as all of them have a transparent democratic system based on the rule of laws.

A trade negotiation between India and the UAE for a Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) is currently at the final stage and is expected to be concluded in early 2022. India has also expressed willingness to negotiate a trade agreement with the US in the spirit of reciprocity and equality.

Though India has been able to manage a trade surplus with the US, the large North American market remains largely untapped. India’s export basket to the US continues to be dominated by traditional products like tea, coffee, polished gems, textiles, carpets, and pharmaceutical products.

A fairly balanced trade agreement with the US can help in opening up the market for Indian manufacturers of engineering goods, chemicals, finished leather goods, steel, and toys, and in increasing India’s share in American imports, currently at 2%. The revival of the India-US Trade Policy Forum (TPF) in November this year and the establishment of the QUAD framework are encouraging signs, however more engagements at the official level on specific issues are needed to sort out hitches related to IPR, and other market access issues.

In 2022, India will have to embrace reforms with unorthodox measures for inclusive economic growth. Globalisation and easy trade flow have no alternatives and no country has realised prosperity in isolation. Engaging meaningfully with the rest of the world will show the path of long-term prosperity. It is high time the country did away with its incremental approach and took bold steps.

India can accomplish the task of increasing annual FDI inflows to $150 billion in the next five years with at least 40% of FDI flowing into the manufacturing sector through systemic reforms. The target of reaching the GDP milestone of $5 trillion must include an export target of $1 trillion since producing more for domestic consumption is no longer enough to propel India into the group of middle-income countries.

Krishna Kumar Sinha is an industrial policy and FDI expert based in New Delhi. His last assignment was as an industrial adviser in the department of industrial policy and promotion, DIPP, currently known as DPIIT, under the ministry of commerce and industry of the government of India.