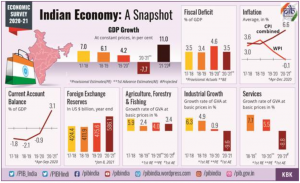

The Indian economy expanded 5.4% in the October-December quarter, much slower than in the previous two quarters, forcing the National Statistical Office to cut its growth forecast for the financial year ending March to 8.9% from the earlier projection of 9.2%.

While the economy has managed to notch up decent growth numbers, it is still troubled by slack demand and rising prices. The Reserve Bank of India had pegged GDP growth rate at 9.2% for the current financial year, while projecting a lower 7.8% for 2022-23. The RBI left key policy rates unchanged to support economic recovery despite inflation testing its tolerance limit. The economy grew 8.4% in the September quarter, sharply lower than the 20.1% in the June quarter.

READ I Timely action on inflation needed to avert hard landing, says Maurice Obstfeld

The NSO puts the real GDP for the current financial year (2011-12 prices) at Rs 147.72 lakh crore, compared with the first revised estimate of Rs 135.58 lakh crore. The GDP for the December quarter stood at Rs 38.22 lakh crore, compared with Rs 36.26 lakh crore in the same quarter of the previous year.

Slow growth to hurt Indian economy

Slow growth may hurt investment and employment creation in the economy. The biggest worry for the government is persistently low consumption demand which is yet to regain pre-pandemic levels. The pandemic and lockdown measures hit sectors such as travel, tourism, restaurants and small businesses, resulting in the loss of a large number of jobs.

Rising crude prices in the aftermath of the Russian invasion of Ukraine could further cause problems for the Indian economy. The country imports close to 80% of its oil needs. The rising prices of crude oil may fuel inflation and hit the rupee further. A 10% increase in crude prices could pare the growth rate by 0.2 percentage points.

READ I Easing of public debt burden will cause economic disruption

Inflation based on the Consumer Price Index stood at 6.01% in January 2022, higher than the 5.66% in the previous month. While the rate is just above the RBI’s comfort level, it masks the problem of rising food inflation which soared to 5.4% in January from sub-1% levels in October 2021. This spike is on account of a 24% increase in edible oil prices during the period, while costlier fruits, vegetables and cereals accentuated the problem.

Inflation in the category of cereals is perplexing. India’s foodgrain policy has contributed largely to this new phenomenon. The country’s foodgrain stock as of February 1 was 87 million tonne, more than four times the required buffer stock. By keeping such huge stocks in its godowns, India is stifling the availability of cereals in the domestic market, thus fuelling inflation.

Moody’s Investors Service had raised its growth projection for the financial year 2022-2023 to 8.4% from 7.9%, while cautioning of the rising oil prices and supply disruptions. Moody’s higher growth projection is based on the speed of the recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic. Fitch Ratings, however, kept its earlier projection of 10.3% unchanged.