The Covid-19 pandemic has adversely affected India’s informal sector. However, discussions on this adverse impact have suffered from a lack of essential evidence due to the absence of comprehensive data at the national level. Recently, the National Sample Survey Office of the ministry of statistics & programme implementation released the fact-sheet on the Annual Survey of Unincorporated Enterprises (ASUE) for 2021-22 and 2022-23.

The ASUE 2021-22 & 2022-23 fact-sheet provides aggregate-level statistics on non-agricultural enterprises in the informal sector. This is the first post-pandemic official survey data on informal sector enterprises. Prior to this, data was available for 2015-16 (73rd round of NSSO).

READ | Steel industry in race to forge a sustainable future

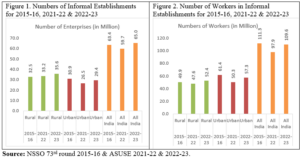

The role of the informal sector has been critically important for the Indian economy. Although often overshadowed by the formal sector, the informal sector absorbs a significant portion of the Indian labor force. According to the latest data on unincorporated sector enterprises (2022-23), there are an estimated 65 million informal establishments providing employment to 109.6 million workers, as per the ASUE fact-sheet. The informal sector in India is known for its flexible and diverse productive activities.

Additionally, this sector has been a significant support to the Indian formal sector. Conversely, informality puts workers at a higher risk of vulnerability and precariousness. The vulnerability of informal labor became particularly evident during the Covid-19 pandemic. According to the ILO (2020), more than 2 billion laborers engaged in the informal sector worldwide were severely affected by the pandemic as their livelihoods depended on daily earnings.

Establishments and workers: Urban areas bear the burden

The effects of Covid-19 on the Indian informal sector are evident from the latest fact-sheet. A comparison between the previous NSSO data of 2015-16 (73rd round) and the estimations of 2021-22 shows a significant decline in the estimated number of establishments from 63.4 million to 59.7 million. However, in the successive year of 2022-23, there has been a recovery with estimated numbers returning to 65.0 million.

Indian urban areas were the most affected, witnessing a decline in the estimated number of establishments from 30.9 million in 2015-16 to 26.5 million in 2021-22, the immediate post-pandemic year. This decline can be linked to the mass movement of migrants from urban to rural areas due to the slowdown of economic activities in urban regions.

Although the data reveals some recovery of the urban economy, with the number of establishments reaching 29.4 million in 2022-23, it has still not returned to pre-pandemic levels. Conversely, Indian rural areas have experienced a continuous rise in the estimated number of establishments from 2015-16 to 2021-22 and 2022-23. This may be attributed to the reverse migration of skilled workers from urban to rural areas, who started their economic activities in rural spaces and decided not to return to urban areas, as reported by PLFS 2020-21 data on migration.

The workforce engaged in the Indian informal sector has witnessed a more noticeable decline compared to the number of establishments. From 2015-16 to 2021-22, the number of workers declined by 13.4 million. While there was a recovery in 2022-23, the figures are still below the pre-pandemic level (2015-16). Urban areas have been the major source of this decline, losing as many as 11.2 million workers between 2015-16 and 2021-22. Conversely, the number of workers in rural areas was less affected than in urban areas during the pre- and post-Covid periods. However, in 2022-23, the estimated number of workers in rural areas increased by more than 2.5 million compared to 2015-16.

Two key implications

These trends convey two important implications. First, urban areas demonstrated sensitive vulnerability to unexpected external shocks like Covid-19. The significant decline in the number of establishments and workers in urban areas highlights this vulnerability, reflecting the harsh effects of economic disruptions on informalization. Second, besides Covid-19, the Indian informal sector has faced two major policy interventions, namely demonetization and the Goods and Services Tax (GST), as claimed by many. These policies likely placed direct stress on the informal sector, hindering its growth prospects. The collective impact of these major external disruptions caused near stagnation in the figures of the informal sector over the last 6-7 years.

Productivity rise: Preliminary evidence

A remarkable revelation of the ASUE 2022-23 is a substantial rise in the productivity of the informal sector, represented by the gross value added (GVA) per worker, observed from 2015-16 to 2022-23. The data shows that GVA per worker is at an all-time high for urban areas for all three time intervals. Specifically, the GVA per worker increased by 41.8 percent for all of India. The incremental trend was also witnessed in both rural and urban areas, though rural areas experienced significantly higher growth (51%) compared to urban areas (33.4%).

The main reason for this occurrence is the significant rise in GVA and the slow growth of employment. Moreover, these trends highlight the adaptability and resilience of the Indian informal sector. Despite facing major challenges over the past decade, such as demonetization, GST implementation, and the Covid-19 pandemic, the informal sector has managed to produce more with less labor.

These trends indicate that informal establishments are finding ways to increase productivity, possibly by improving their management practices, adopting grassroots innovations, and enhancing market integration. However, it is important to note that when calculating GVA at constant prices, the rise in productivity might not be as high. Furthermore, concluding a drastic rise in productivity based solely on GVA and the number of workers might be premature. A deeper analysis with more variables will be necessary once the full report and unit-level data are released by the NSSO.

Tareef Husain is assistant professor at economics department, Galgotias University, Greater Noida.

Puneet Kumar Shrivastav is assistant director, National Institute of Labour Economics Research & Development, Delhi.

Samar Kumar Mishra is assistant professor at Economics Department, Galgotias University, Greater Noida.