The last 30 years saw India emerging as a major economic power of global standing. Currently, it is one of the fastest growing major economies in the world. While it strives to become a $5 trillion economy, India has a major inequality problem. While the years since 1991 have been the best in terms of GDP growth, there has been a sharp increase in income inequality.

The World Inequality Report 2022 shows India as a very unequal country, where the poorer half of the population holds just 13% of the national income. The report says that the richest 10% of the population controls 57% of the GDP. The rich are getting richer while the poor are yet to have a good quality of life.

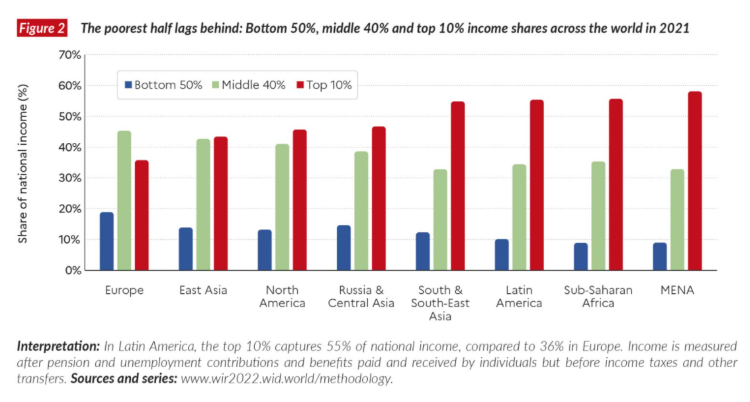

India is not alone in this predicament. Income inequality has been on the rise globally since the 1980s because of a series of liberalisation and globalisation measures. South Africa was the most unequal country in 2019 which means the benefits of growth are cornered by a few and do not trickle down to the poor majority of citizens. India is among the most unequal countries, featured at the top with a score of 0.832 along with Surinam, followed by The Bahamas (0.828).

READ I Universal health coverage makes sense – both in ethics and economics

Inequality on the rise globally

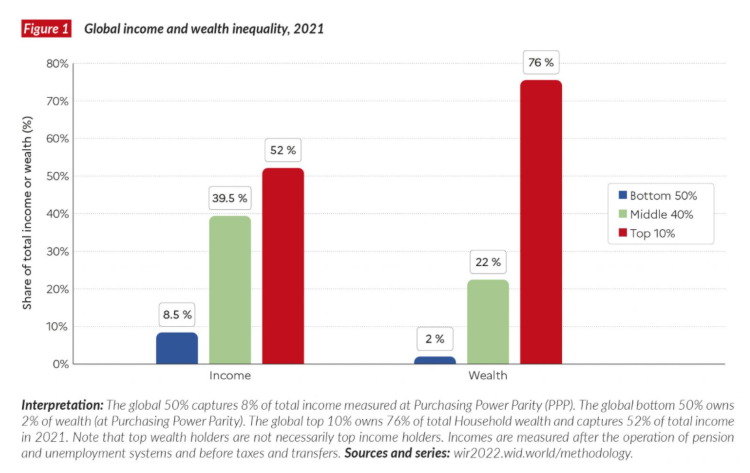

The easiest way to understand the rising inequality inequality is a study of the income distribution between governments and the private sector. While the countries became richer in the last 40 years, the share of income of the governments has shrunk. This has affected their capacity to tackle inequality. The rising inequalities also have a lot to do with the disproportionate share of wealth cornered by global multi-millionaires.

Inequality stems from the disparity in growth rates between the richest and poorest segments of the population. The richest saw their wealth growing at 6-9% annually since 1995, while average wealth grew at 3.2%. For India, a global power with a population of 1.3 billion, this is a huge concern. It leads to poor performance in the world poverty index. India does have a plethora of schemes for social protection. It is important to understand that social protection is the right of a citizen which helps them climb the equity graph.

READ I Covid-19 comes back to push world economy to the brink

Indian billionaires became richer by 35% during the lockdown announced by the government to curb the spread of Covid-19, says The Inequality Virus, the India supplement of Oxfam’s inequality report. The report says the added wealth of the richest 11 Indians during the pandemic could fund the health ministry for 10 years. In contrast, 92 million jobs were lost during the same time, roughly three-fourths of the total jobs in the country.

Oxfam ranks countries based on their policies and actions in public services (health, education and social protection), taxation and workers’ rights. India is ranked 129 among 158 countries on these parameters. Such damning reports call for introspection. India needs to have a better targeted delivery of social protection using social registries such as SAMAGRA , a common household database used by several states. SAMAGRA captures all the government assistance, effecting a shift in thought process from welfare to entitlement.

SAMAGRA can also document India’s informal sector in real time. The population data indicates high fertility rates in Bihar, UP and Jharkhand. These are the states that contribute most to the inequality index. The high rank in taxation (19th) and low rank in public services (141st) clearly indicate poor targeting of social protection measures. The aggregated number of achievements may sound good, but it is not an indicator of the success of welfare measures.

India has no option but to improve its targeting mechanisms for its programmers and availability of funds is not an issue. Policy makers need real time data to improve the country’s equality rankings. High inequality is a time bomb waiting to explode. India needs to end economic exploitation of masses, and ensure that the needy have access entitlements.

Dr Aruna Sharma is a New Delhi-based development economist. She is a 1982-batch Indian Administrative Service officer. She retired as steel secretary in 2018.