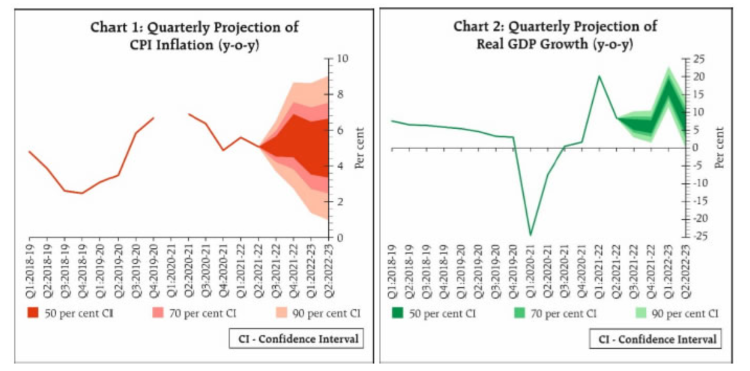

The Reserve Bank of India’s monetary policy committee meeting earlier this week left the repo rate and the accommodative policy stance unchanged, while forecasting benign inflation for the rest of this year as well as the next. The central bank has projected the inflation to cool down to 5.3% in the current financial year and further ease to 4-4.3% by the end of the next financial year.

The inflation forecast made by the RBI in its monetary policy statement does not look very convincing as the rise in prices is expected to stay in the near-term because of high input costs and supply chain disruptions. High raw material prices, transportation costs, shipping delays and supply chain disruptions have led to cost-push inflation. These conditions are showing no signs of abating at least in the short- and medium-term. Moreover, high inflation in most world economies is likely to be reflected in India as well.

READ I Cryptocurrency: India set to chart middle path between ban and free trading

Retail inflation ended the declining trend and rose to 4.5% in October from 4.3% in the previous month on high vegetable prices due to crop damage from heavy rains. The sharp increase in vegetable prices is expected to ease with winter arrivals. Sowing in rabi season is expected to top last year’s acreage. The government has managed to stop the pass-through of high international edible oil prices.

Fuel inflation triggered by globally high prices of liquefied petroleum gas and kerosene rose to an all-time high of 14.3%. Core inflation remained high at 5.9% in September and October, pushed by high prices of clothing, footwear, health, transportation and communication. One of the reasons why RBI projections sound unconvincing is that high inflation in India is not a post-Covid phenomenon. India was already under the grip of inflation when the pandemic struck. Retail inflation was above RBI’s comfort zone of 2-6% for most part of 2020.

READ I Farm laws must widen MSP coverage, ensure profitability

High inflation in US, Eurozone

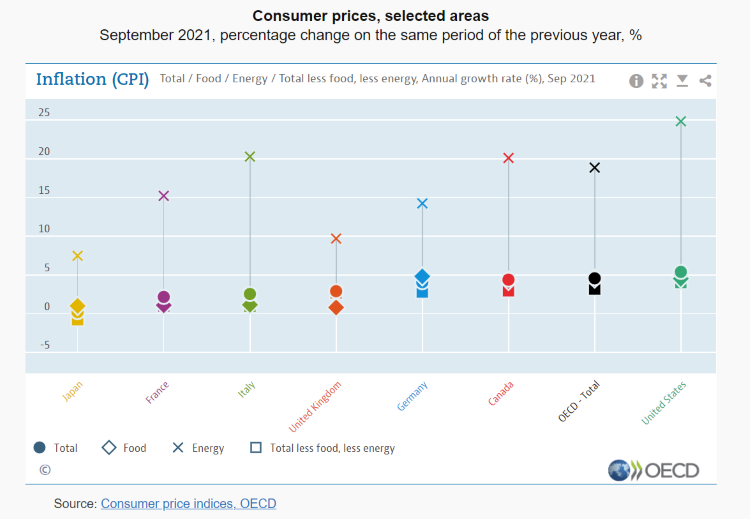

Moreover, some of India’s important trading partners such as the US and Eurozone are also experiencing high inflation that will reflect in the country’s inflation numbers. The US is expecting a 4.9% annual increase in November CPI. Federal Reserve chairman Jerome Powell had said last week that the central bank must brace for the possibility that inflation may not come down in the second half of 2022. The consumer price index for November is expected to have shot up 6.8% compared with 6.2% in October, which itself was the highest in 31 years.

Inflation in OECD countries rose to 4.6% in September 2021, compared with 1.3% in September 2020. The annual inflation rose sharply to 3.4% in September in the Eurozone, from minus 0.3% in the same month last year. But the figure was much lower than in the OECD area and in the United States where inflation shot up to 5.4% in September.

Energy prices rose 18.9% in the OECD area in the last one year, the highest rise since September 2008. Food inflation rose to 4.5%, compared with 3.5% in August. If food and energy components are taken out, OECD annual inflation was higher by 3.2%, the highest rate since April 2002.

The RBI’s decisions to keep the repo rate unchanged and retain the accommodative policy stance were on expected lines as higher policy rates could have affected the Indian economy’s fragile post-Covid recovery. The central bank expects the economy to grow 9.5% in the fiscal year ending March 2022 unless a third wave of Covid-19 causes a resurgence in Covid-19 cases. The Indian economy grew 8.8% in the second quarter in September, while the growth rate was 20.1% in the first quarter.

“The domestic recovery is gaining traction, but activity is just about catching up with pre-pandemic levels and will have to be assiduously nurtured by conducive policy settings till it takes root and becomes self-sustaining,” RBI said in its policy document.

The repo rate or the rate at which RBI lends to commercial banks is currently 4%, while the reverse repo rate at which the central bank borrows from banks is 3.35%. High commodity prices and a flareup in vegetable prices saw inflation ruling high in October and November despite interventions by the government to keep prices under control.

The biggest worry is private consumption which still remains below pre-pandemic levels, while the government doesn’t have enough elbow room to push public spending. A possible third wave of Covid-19 and the fast-spreading omicron variant could threaten the current recovery, the statement said.