India’s decision not to join the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership in 2019 has been one of the most hotly debated topics within and outside the country. The World Bank’s India Development Update released on Tuesday, has urged India to reconsider its stance on the RCEP, reigniting this conversation. As India pursues an ambitious target of achieving $1 trillion in exports by 2030, the jury is out on whether the country should join RCEP. While there are clear potential economic gains, there are also significant risks that could harm the country’s long-term economic goals.

RCEP is a free trade agreement among 15 countries, including the 10 ASEAN nations and five key trading partners — China, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand. Signed in November 2020, RCEP seeks to reduce tariffs and trade barriers across the region, harmonising rules of origin, e-commerce regulations, and intellectual property protections. The agreement covers nearly 30% of the world’s population and economy, making it the largest trade bloc globally.

READ | Achieving resilience: The new boardroom mandate

Potential benefits of joining RCEP

India’s participation in the RCEP would open up markets across the 15-member trade bloc, which includes ASEAN countries, China, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand. Joining would potentially allow Indian businesses greater access to these large consumer bases. Given the trade bloc’s size, India could benefit from lower tariffs and increased export opportunities.

One of the World Bank’s key arguments is the potential for India to integrate more deeply into global value chains. RCEP member countries are significant players in these value chains, and India could leverage this to boost its manufacturing and services sectors. As global companies move toward ‘China Plus One’ strategies, India could position itself as a strong alternative, offering a stable and diverse market for foreign investments.

Various studies estimate that India could gain as much as $60 billion in income by 2030 if it joins RCEP. Even though the methodology of these studies has been criticised, the underlying argument remains — joining a major trade bloc could stimulate trade and investment flows, contributing to economic growth. Additionally, in an interconnected world where trade is often seen as a driver of growth, being part of RCEP would send a signal of India’s commitment to regional economic integration.

The economic and strategic concerns

India’s trade imbalance is one of the most critical arguments against joining RCEP. According to trade policy think tank GTRI, many RCEP member countries, including Japan, South Korea, and ASEAN members, have seen their trade deficits with China balloon since joining the bloc. India already has a substantial trade deficit with China, exceeding $85 billion in FY2024. Joining RCEP, which involves zero-tariff access to Chinese goods, could exacerbate this problem, undermining India’s domestic manufacturing and Atmanirbhar Bharat initiative.

India’s cautious approach to trade with China has been validated by the pandemic, which exposed the risks of overreliance on China-centric supply chains. By staying out of RCEP, India has been able to diversify its trade partnerships, an approach that aligns with global efforts to reduce dependence on a single country for essential goods. In this context, joining RCEP could potentially reverse these gains and tie India closer to Chinese supply chains at a time when strategic decoupling from China is a priority for many global economies.

While supporters of RCEP argue that India could benefit from increased trade in services, trade data suggests that the actual gains would be modest. Moreover, the primary benefit projected from joining RCEP would come from an increase in imports rather than exports, especially in highly subsidised sectors like agriculture and manufacturing. Such an outcome could severely undermine India’s self-reliance goals and negatively impact its small and medium enterprises (SMEs), which are already struggling with payment delays and competition from cheaper imports.

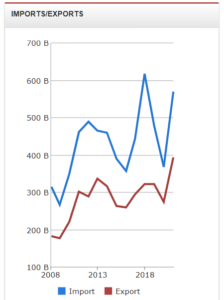

India already has Free Trade Agreements with 13 of the 15 RCEP members, including ASEAN, South Korea, and Japan. Despite these agreements, India’s trade deficits with these countries have steadily increased. For instance, between 2007-09 and 2020-22, the trade deficit with ASEAN grew by 302.9%, with South Korea by 164.1%, and with Japan by 138.2%. The rise in these deficits suggests that any further tariff concessions under RCEP could lead to more harm than good, particularly in sectors where India is already at a competitive disadvantage.

Strategic balance in trade

India’s decision not to join RCEP was not just about economic calculations — it was also a strategic move. By opting out, India has been able to negotiate better trade terms with key partners on its own terms. The country has successfully signed FTAs with Australia, the UAE, and is negotiating with the UK and the EU, ensuring that these agreements are tailored to India’s specific needs, including the protection of vulnerable sectors like agriculture and dairy.

Moreover, the global geopolitical landscape is shifting. The rise of new trade frameworks, such as the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF), offers India alternative platforms to engage with the global economy without being bound by the terms of RCEP. These platforms can provide India with access to new markets and investments while maintaining its strategic autonomy.

While there are undeniable advantages to India joining RCEP, the potential downsides—such as large trade deficits, increased dependence on China, and limited gains for key sectors—cannot be ignored. The World Bank’s suggestion to reconsider the decision does raise important questions about India’s regional integration strategy. However, India must continue to prioritise its long-term economic goals, particularly in terms of self-reliance, job creation, and strategic autonomy.

Rather than joining RCEP, India may be better served by strengthening bilateral and regional trade agreements, enhancing its competitiveness in global value chains, and focusing on strategic sectors like pharmaceuticals, digital trade, and green technologies. In a world where economic alliances are constantly evolving, India’s cautious, data-driven approach to trade may well be its strongest asset in navigating the complex global landscape.

Anil Nair is Founder and Editor, Policy Circle.