Temporary roadblocks to India-UK FTA: The multilateral trade guard-rails that once kept tariff spats in check are buckling. Earlier this month the World Trade Organisation trimmed its forecast for 2025 merchandise-trade volumes from modest growth to a 0.2% contraction, warning that President Trump’s blanket reciprocal duties could lop an additional full percentage point off global commerce if retaliation spreads.

Against that backdrop, capitals are speed-dating for FTA partners. Britain has just slipped into the trans-Pacific CPTPP club and is scouting new pacts to offset its post-Brexit losses, while Asia-Pacific and Latin American blocs race to ring-fence supply chains.

For India, clinching an accord with the UK would lock in tariff certainty before Europe’s looming carbon border levies and any fresh shocks from the White House redraw the rules again.

READ I India’s high-stakes gamble in higher education

India-UK FTA: Warm words, cold reality

Commerce and industry minister Piyush Goyal landed in London this week for a 48-hour push he hoped would “co-create the next chapter” in India-UK economic relations. Over two days he toured Downing Street, Lancaster House and boardrooms packed with CEOs from Revolut to De Beers, talking up India’s fintech boom and diamond hub ambitions. Foreign secretary David Lammy and business and trade secretary Jonathan Reynolds repaid the charm with fulsome praise and an invitation-only reception. Yet every public statement skirted the one acronym the audience was waiting to hear: FTA.

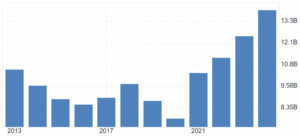

India imports from UK

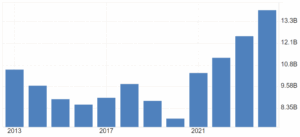

Indian exports to the UK

Behind closed doors negotiators tried—unsuccessfully—to sew up the 26-chapter agreement. A formal signing ceremony had even been tentatively blocked on diaries, but talks broke with four or five issues still unresolved, according to officials familiar with the discussions. No new timetable was announced. For the moment, India’s annual trade with the UK remains stuck around £41 billion.

The stubborn sticking points

Officials will not list the final roadblocks, but business groups on both shores point to the usual suspects. Rules of origin still dictate how much imported content a product may contain before it counts as Indian or British—vital for complex auto and electronics supply chains. Short-term service visas, once Delhi’s marquee demand, remain politically toxic in Westminster; London’s latest offer reportedly adds barely 100 extra permits a year. Meanwhile Indian whisky distillers want the UK’s three-year maturation rule relaxed, and British carmakers want India’s 100 per cent tariff on imported vehicles brought closer to ASEAN levels.

Time is not on negotiators’ side. The UK is working with Brussels to link carbon markets and align its own Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism by 2027—a move that could slap new charges on Indian steel, aluminium and cement unless a waiver is hard-wired into the FTA.

On the services front, Delhi has already blinked. Reports indicate it now accepts only minor tweaks to Britain’s visa regime, surrendering much of the leverage its formidable IT industry had hoped to wield. That concession places even greater weight on tariff wins for labour-intensive exports such as textiles, which currently face duties of up to 10 per cent in the UK.

Britain, for its part, wants deep cuts on Scotch (now taxed at 150 per cent) and a phased glide-path to lower car duties—ideally before its first CPTPP tariff reductions kick in this December. Any failure to move the dial on manufactured exports risks undercutting London’s narrative that post-Brexit trade can deliver quick, visible gains.

What a deal could deliver

Both governments still tout the prospective gains. Treasury models suggest zero duties on Scotch, wine and premium autos could boost UK exports by £1 billion a year; Delhi counters that cheaper machinery and medical devices from Britain will widen India’s investment pipeline. Yet the asymmetry is stark: average UK duty on Indian goods is just 4.2%, while India’s average tariff on British products is 14.6%. In other words, most of the headline liberalisation will occur on the Indian side.

For India the calculation is strategic as much as economic. An agreement with a G7 power strengthens its claim to be a rule-shaper rather than a rule-taker—useful as New Delhi pursues parallel talks with the EU and the Gulf Cooperation Council. For Britain, fresh proof it can still sign meaningful trade deals underpins Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s push to pivot from Brexit wrangling to growth.

The failure to land the deal this week does not doom it. Goyal heads next to Norway and Brussels, while Reynolds will keep his team on standby for remote drafting sessions. But the window is narrowing: India gears up for crucial state elections in July, and the UK will soon enter its autumn budget season.

Outside, the trade weather is deteriorating—tariffs rising in Washington, carbon walls sprouting in Europe and America, supply chains re-shoring in fits and starts. In that environment an FTA may not be a panacea, but it is a lifeboat. The longer Delhi and London take to climb aboard, the rougher the seas will become.