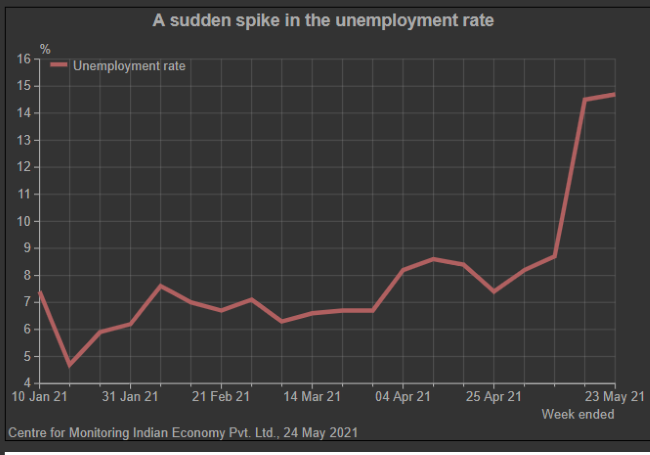

The second wave of Covid-19 is leading India to an unprecedented unemployment crisis. The jobless rate jumped to 11.9% in May from 7.97% in April. According to CMIE data for May, unemployment rate is 14.73% in urban areas and 10.63% in rural areas, the highest since May last year. Santosh Mehrotra, visiting professor at Centre for Development, University of Bath, UK, is known for his work in areas such as labour, employment, and skill development. He spoke to Policy Circle’s Anil Nair on the Indian economy and the unfolding unemployment crisis in the country. Edited excerpts:

Do available numbers reflect the current level of unemployment in the country? Is it possible to draw reliable unemployment data from other sources?

The current employment numbers are coming from CMIE, which is a reliable source. NSS numbers are available, but they are published with a massive delay. CMIE data is reliable for the following reasons. One, the sample size is larger than the NSS. Two, it covers both organised and unorganised sector. Three, it covers both rural and urban areas. Fourth, the panel goes back to the same people every three months.

Finally, they have a fast turnaround because they collect the data on a tablet. So that turnaround is immediate. Which is the reason why when Mahesh Vyas writes, he can give you data on a weekly basis. First of all, no element of doubt when he reports a major increase in unemployment in April and May, which is hardly surprising. The lockdown has been in place and workers have gone back to the villages.

READ I Worst over; GDP growth will recover faster than forecasts in FY22: Arvind Virmani

What is the state of rural employment at present? Can agriculture absorb a major chunk of newly unemployed people?

So, let’s turn to the rural employment situation. Let’s look at this historically. Until 2004-05, for over 50 years, the absolute number of workers in agriculture was increasing. This is terrible because it is the opposite of what should be happening if a country was transforming itself structurally. For the first time, growth was so rapid after 2003 that millions of workers started moving out of agriculture.

There was always rural to urban migration, but the numbers were not enough to reduce the absolute number of workers in agriculture. This decline happened for the first time in India’s history post 2004-05. And that has continued since then for15 years, but at a slow pace in the last seven-eight years. More important point is that now post-Covid, since April last year, the absolute number of workers in agriculture has increased sharply. What we are seeing is a reversal of what was happening for 15 years.

So, let’s come to the second part of your question. Can agriculture absorb these people? Of course, it cannot. Which is what is showing up again in rising open unemployment in April and May 2021. But the more important point is that we should not focus only on unemployment or open unemployment. You have to appreciate how unemployment is defined. Someone has to be looking for work and not finding it to be unemployed. But what if people after looking for work and not finding it drop out of the labour force and stop looking for work. And that is called the labour force participation rate, which is defined on the denominator of working age population.

READ I Monetary policy must keep rates unchanged, lower FY22 growth projection, says Abheek Barua

If the young population is going out of the labour force, what will happen to the demographic dividend India enjoys at present?

The demographic dividend happens when the working age population is rising and the dependent population, meaning those under 15 and those over 60, is falling. In other words, it is a very good period in the life of a nation. It comes once in the life of a nation. But what we are seeing since 2012, because of the mismanagement of the economy, the labour force participation rate is falling.

You mean to say that India is losing this window of opportunity?

Yes. We are in the process of losing it. Non-farm jobs are not growing at the rate at which young people are entering the labour since this government came to power. And non-farm jobs are not growing because the economy has slowed down because of the economic mismanagement. Unemployment rising in a poor country is a serious development because it is happening on a fall in labour force participation rate, especially among women.

Secondly, it is happening in a country where young people are getting better and better educated. In the last 15 years, this is a transformation that has happened across the country. It doesn’t matter whether you’re in Kerala or in UP. This is a transformation which has swept across the whole country. This means that these young people will not work in agriculture. Earlier generations have dropped out of school and ended up working in agriculture.

If you look at Kerala, unemployment rate is very high. You will be shocked to know that that the open unemployment rate was 18% in 2012 in Kerala, which was among the highest even then. But it has shot up to 36% in 2018-19. This is youth unemployment, between the ages 15 and 29 years of age. It is highest in Kerala as young people are better educated than in the rest of the country. But it is bad enough in the rest of the country too. I’m talking about pre-Covid period. Imagine how serious the situation may be right now.

READ I Monetary policy: Growth, jobs bigger concerns for RBI than inflation

You look at the following scenario. You have a rising share of young people in the population and a major share of these young people are better educated. You have overall jobs rising on a lower rate. Before Covid, unemployment rate had risen to a 45-year-high. When the pandemic broke, even after lockdown was lifted, unemployment was worse than it was pre-pandemic. And on top of that, post pandemic unlock, those who are employed are actually working fewer hours. For instance, people in organized sector, who have lost jobs have become self-employed. This is tragic because in self-employment your earnings maybe actually lower.

Wages that had been rising till 2012, were stagnant till 2019, or falling. Since the increase in joblessness during and post-pandemic, wage have fallen for regular and casual workers, and for self-employed earnings have declined. The end result is a rise in the number of poor people. The CMIE data is showing very clearly that those who are self-employed are working fewer hours. They’re not working the full eight hours and their earnings are lower.

There’s yet another phenomenon going on that when millions of people return to rural areas from urban locations, then the open labour market wages tend to fall as there are more workers and not as much jobs. This is what is the general crisis that has gone on for a whole year since the Covid outbreak. But there was a saving grace in the first wave of the pandemic, which is not present in the second wave. And that is the rural spread of Covid was much less. Now the rural spread is much more severe.

READ I Legends of the fall: Govt, RBI must clarify on cryptocurrencies

What are the prospects of economic recovery? Indian economy is expected to have a V-shaped recovery post-Covid…

The implication is that in 2020, if you ask any government supporter or government bureaucrat or BJP spokesman, they would tell you there is a V-shaped recovery happening post lockdown. And they would say that the agriculture sector is bouncing back because of the good monsoon; that held true last year. Good monsoon will hold true this year also.

The bad news this year that three things will happen. One, pandemic has spread to rural areas. When BJP spokesmen say that agriculture will do well even this year because the monsoon is good, they’re not accounting for the following facts. One that the pandemic has spread to the rural areas, and there will be fewer workers available because they are sick.

Two, cultivators themselves would have become sick and therefore will not be able to work. And three, for these reasons demand will fall even more. Millions of labourers have gone back to rural areas last year and some will be back to rural areas in the second wave. That means things are back to square one in terms of supply of workers while labour demand will drop (as I explained above). As a result, the open market wages are going to fall in rural areas like last year.

The overall impact of this is that aggregate demand in the economy will be impacted as 65% of India lives in rural area. This means that the entire organized sector will also be impacted. This is going to play out in FY22. So, the expectations of 10% growth that the government was talking about in FY22, which was going to offset the 10% contraction in the economy in FY21, will not materialise. GDP in FY22 will still be lower than in 2019-20. Per capita income will be even lower in FY22 than it was in FY20. And in any case, the government was underestimating how badly the unorganised sector and MSMEs are faring.

But independent agencies such as IMF and World Bank back the government numbers. The CSO estimate for GDP growth is in sync with the IMF projection…

That is because international agencies rely completely on government data for their forecast. They don’t have separate estimates and this has always been the case. The situation is definitely grim. The language that the government has been using so far has been aggressively optimistic; this is part of the ‘Positivity Unlimited’ agenda launched last month by the RSS chief.

Unfortunately, they don’t seem to recognise the enormity of the crisis. They are always in denial. About a month ago, the chief economic advisor said that the impact of the second wave OF Covid-19 is not going to be very large, which was shocking even then; he repeated it when the latest GDP numbers were announced a few days ago.

What’s the state of India’s manufacturing and services? Will these sectors be able to absorb the young people who will enter the job market?

Let’s look at services. All contact-based services have been impacted badly. Also, all manufacturing that requires physical presence of workers have been impacted adversely. Now this has to be qualified by saying that there are certain services, which of course did extremely well. So, eCommerce did extremely well in the whole period. IT and BPO services are not particularly impacted because you can continue to work from home.

It’s another matter that the rich countries themselves have contracted in 2020, but they put in place substantial fiscal stimulus last year. The vaccination program also proceeded well in those countries. So, they are going to bounce back. India is among the countries that will suffer as the situation last year was managed badly. Plus, India injected a smaller fiscal stimulus than even other emerging market economies, despite the fact that our economy contracted worse than any other G20 country. The result will be long-term damage to both jobs and GDP growth into the future.

The government has put the contraction figure at 7.3%…

The government has underestimated the impact on the unorganized sector. If the estimation is correct, we wouldn’t be seeing such massive unemployment. The labour force participation also has declined. People have got discouraged after looking for work and not finding it. Many of them have dropped out of the labour force. In other words, they stopped looking for jobs. On top of that, you have open unemployment, leading to falling wages. The number of people looking for jobs are much greater than the jobs that are on offer.

The government is reporting great GST numbers month after month…

That’s because of the organised sector. The organised sector consists of companies listed on BSE and NSE, as well as the unlisted ones. The latter are mostly smally and medium enterprises. Let’s remember that manufacturing bounced back post the first lockdown. Many of the organised sector employees could work from home. The point I’m making is that the listed companies were able to function. The result was that they have made good profits.

Listed companies (CMIE reported) made extraordinary profits in the quarter ended March 2021. This would be the third consecutive quarter of superlative profits. Profits sank in the March and June 2020 quarters but in the quarter ended September 2020, 4,406 listed companies reported a net profit of Rs.1.52 trillion. This was 30 per cent higher than the highest profit earned anytime in the past. In the quarter ended December 2020, the profits scaled up further to Rs.1.53 trillion. In the March 2021 quarter, just 935 companies booked a profit of Rs.1.58 trillion.

Also, please appreciate that the organized sector companies cut their worker strength, and in some cases effected salary cuts. More than 15 million organized sector jobs were lost last year. And many of those who didn’t lose jobs were being paid lower salaries. So, listed companies made profits on the back of cost cuts. This is one of the reasons, not the only reason why Nifty and Sensex are doing well. There are two other reasons for the booming capital market. One is that the central banks in rich countries pumped liquidity into the system. So, international banks that are flush with funds invested in India for the arbitrage between returns in India and returns back home.

In the West, a large number of middle class and upper middle-class people (as well as in India) who are working from home were spending less. They’re not spending in restaurants, not traveling, and not going on holidays. So, they have increased savings that they are investing individually. Indian retail Investor numbers were rising in 2021 by 1 million per month. So, individual retail investors are also coming in with their additional savings.

Because of these reasons, there is a disconnect between the upswing in the capital market and the real economy. The CMIE numbers show that 7 million jobs were lost in April alone, almost half of which was in the unorganised sector.

What is the condition of MSMEs? How badly are they affected?

Over 15 million jobs were lost during May 2021. May 2021 is also the fourth consecutive month of a fall in employment. The cumulative fall in employment since January 2021 is 25.3 million. Employment in January 2021 was 400.7 million. This has dropped to 375.5 million.

CMIE’s Household Survey shows that the impact during these two months, particularly in May 2021 was severe on daily wage workers. Of the total 22.3 million jobs lost during April-May, 17.2 million were of daily wage earners. Business persons lost 5.7 million jobs during these two months and salaried employees lost 3.2 million.

MSMEs offer regular jobs to millions of people. They are losing jobs because there is no demand. The aggregate demand has collapsed across the economy. The government should have put in a much bigger fiscal stimulus… and put money in people’s pockets. It should have borrowed more than it did. And, and its fiscal stimulus was barely 2.2% of the GDP in FY21 when the stimulus put in place by rich countries was of the order of 9-10% of the GDP. Forget about rich countries, even emerging market economies put in place a fiscal stimulus of 4.7% of the GDP while India put just 2.2%. We made a massive mistake.

Who advised the government on stimulus? What was the thinking behind not coming up with a large stimulus?

Their thinking is simple-minded. This government thinking is not even sophisticated for a neoliberal government. They genuinely don’t have economists among those taking decisions. The government is run by bureaucrats, not economists. They don’t understand macroeconomics. They pumped liquidity into banks that were already doing badly. The problem is credit growth that they expected did not happen. Viable credit growth cannot happen when aggregate demand is collapsing.

The drivers of economic growth are four-fold: private consumption, investment, exports and government spending. First, domestic private consumption, which accounts for nearly 58% of GDP. That has been shrinking, because as I said jobs and earnings have been falling for several years, and even more since the pandemic. Second, investment to GDP was 31% when current government came to power; it is 27.1% in 2020-21. Third, merchandise exports stood at $315 bn in 2013-14; they never exceeded that number in any year since.

By contrast, exports had risen every prior since 2000. In 2020-21 they are still lower than they were in 2013-14. Finally, government revenues have been impacted by falling growth, so govt expenditure did not make up for the fall. There was a silent fiscal crisis already by 2019, which was out in the open by 2020. The result is the deepest contraction in India’s GDP in independent India.

In other words, the government should have borrowed and come up with a larger fiscal stimulus. The UPA government which was in power put in a fiscal stimulus amounting to 3.5% of the GDP in 2008, during the global economic crisis. And what does this government do in a crisis that was much bigger shock to the Indian economy? It put in place 2.2% of GDP.

So, the MSMEs went on closing. Larger companies have bought some of them out. So, there is greater concentration of wealth taking place. The profits of large companies were rising already. When you are saying that the GST collection is rising, why are you surprised? The profits of larger companies are growing. That means higher tax collection.

There’s a question mark over the students entering the job market. What will happen to them?

They won’t find jobs. This is a serious crisis. The organized sector jobs are being scrapped. The new generation of job seekers are better educated, but most do not possess work-oriented skills. When the economy begins to pick up, they will find that they are not qualified. Massive unemployment will lead to increasing inequality in society and deepen social conflicts.

Anil Nair is Founder and Editor, Policy Circle.