India’s foreign exchange reserves surpassed $600 billion in the week ended June, leading to jubilation among of some economy watchers. With the global economy struck by the Covid-19 pandemic even before recovering fully from the financial crisis of 2007, the steadily increasing forex reserves may seem paradoxical and unbelievable. This also comes in the backdrop of the economy posting a current account surplus after a gap of 17 years, boosted by net capital inflows, both in the form of portfolio inflows and direct foreign investment. Do the foreign exchange reserves and the current account deficit indicate that the Indian economy, especially its external sector, is in the pink of health, or are there any unseen risk lurking behind these numbers?

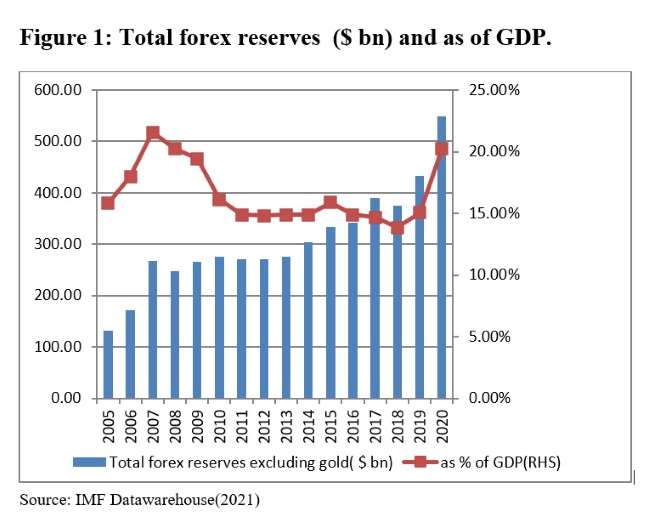

The forex reserves have been witnessing a steep increase due to the rising inflows on the FDI and PFI front on the capital and financial account. There has been a steep increase in India’s forex reserves in the last two years (Figure 1). At $600 billion, the forex reserves are now around 22% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP). But the positive signals from the current account front should be seen in the context of falling overall imports and a sagging Indian economy. In fact, the investment downturn in the Indian economy that started 10 years ago is yet to show any sign of reversal.

READ I G7 to launch ‘green belt and road’ plan to counter China

Remittances, service exports dominate inflows

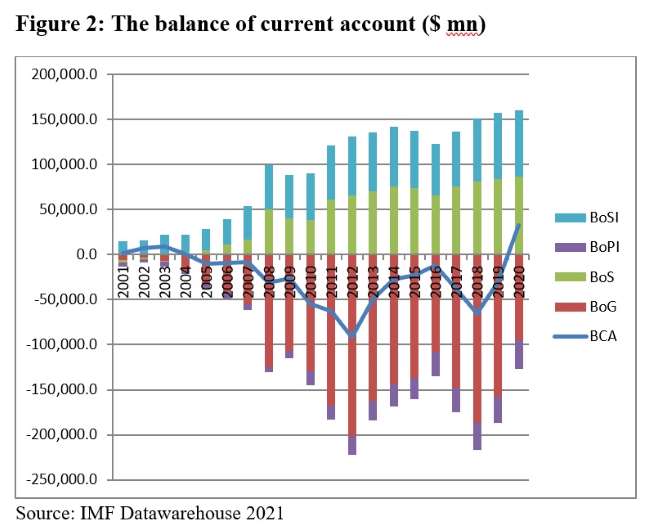

A quick analysis of the balance of payment disaggregates of the last 20 years would be in order. Indian economy saw current account deficits in most years between 2000 and 2020, except for four years (Figure 2). Throughout the period, India had a merchandise trade deficit, but the remittances inflow provided some cushion on the current account front. With more than 17.5 million Indians working abroad (the World Migration Report 2020), India is the top recipient of remittances ($83.3 bn) in the world.

On the invisibles front, i.e., balance on services, India is possibly one of the few developing economies that enjoys a surplus. Despite huge remittances and service exports, India has had a current account deficit because of its huge merchandise trade deficit and net outflows of investment income. In other words, much of the foreign exchange reserves has not been on account of the current account surpluses. There have been a few years like the current one where the levels of imports grew at a slow pace due to low rates of economic growth.

READ I Global minimum tax explained: Abuse of tax havens to end, big tech to come under tax net

Capital inflows boost foreign exchange reserves

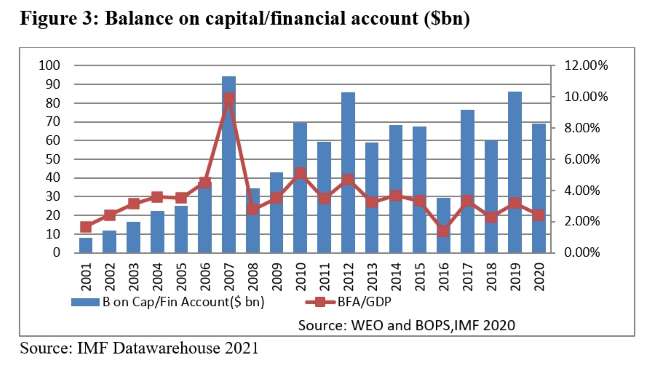

The accumulation of foreign exchange reserves has been on account of the net capital inflows on the capital/ financial account. Other than in the last two years when foreign direct and portfolio investments have been the important contributors to the capital account, external commercial borrowings comprised bulk of the inflows. Non-financial corporations in emerging market economies including India have increased their borrowings from the international market to benefit from the interest rate differential.

None of the last 20 years saw net outflows on the capital account. In 2007, the net capital inflows were as high as $94 bn (9.4% of the GDP), far higher than required to bridge India’s current account deficit. All these years of net capital inflows have been adding to the foreign exchange reserves, as well as to the stock of external debt of the country.

In other words, in contrast to economies like China where the net capital inflows were only supplementing the current account surpluses in adding to their foreign exchange kitty, ours is largely based on the accumulated liabilities over time. In fact, while we have the fifth largest foreign exchange reserves in the world next only to China, Japan, Switzerland and Russia, all these economies have consistently had a positive current account, whereas ours has been largely made out of financial account surpluses.

READ I Climate change tipping points warn against slow progress

One would ask what’s wrong with mobilising financial resources from the rest of the world, particularly when the interest rates are very low? The Economic Survey 2020-21 will help one understand the situation. Of the total stock of external debt of $558.2 billion, 19.1% is of short-term debt of less than one year maturity and 42.4% is of residual maturity. In other words, 61% of India’s external debt (i.e., more than $300 billion) is purely of short-term nature and will mature in the course of the year.

If the economy is able to roll over these liabilities on maturity, there isn’t any threat. But that is only one possibility. Given that the international rates of interest are set to firm up with the vaccination rounds complete in the US and Europe and the green shoots of growth showing up, the interest rate differential that helps India attract capital inflows would cease to exist. In that eventuality, India might be in for a big problem on the external front. It is because of the volatile nature of the short-term loans in its debt portfolio that many countries have resorted to capital controls in a big way, to which India has not been open.

Let’s put the discussion on India’s foreign exchange reserves in perspective. As per the Economic Survey, the overall international financial liabilities (both debt and non-debt) of India are more than twice (210%) its reserves. Therefore, even when the country basks in the glory of the $600 bn forex reserves, a taper tantrum moment like the one witnessed in 2013 could test its quality and sustainability.

(Krishnakumar S teaches economics at Sri Venkateswara College, University of Delhi.)

Krishnakumar S is a New Delhi-based economist. He teaches economics at Sri Venkateswara College, University of Delhi.