The narrative of Environmental, Social, and Governance investments as a panacea for the world’s environmental and social challenges has captivated the investment community and the public alike. However, beneath the surface of this investment trend lies a complex and often misunderstood reality. It is crucial to study ESG investing to understand its limitations in effecting real-world change.

At its core, ESG investing involves incorporating environmental, social, and governance factors into investment decisions. The rationale is that companies mindful of these factors are likely to be more sustainable and, potentially, better long-term investments. While this premise is attractive, the implementation and impact of ESG investing are fraught with complexities and contradictions.

READ I The Arctic standoff: Implications of new western sanctions on Russia

Profit vs planet

A fundamental issue with ESG investments is the concept of materiality used in ESG ratings. These ratings assess how global changes like climate risks and social trends may impact a company’s financial performance, rather than how the company affects the world. This single materiality approach prioritises financial returns over environmental or social impact, leading to a situation where the investment does not necessarily contribute to broader sustainability goals. For instance, an ESG fund may include companies like Exxon, Chevron, and ConocoPhillips, which, despite their contributions to carbon emissions, might score well on certain ESG metrics due to their financial robustness or governance structures.

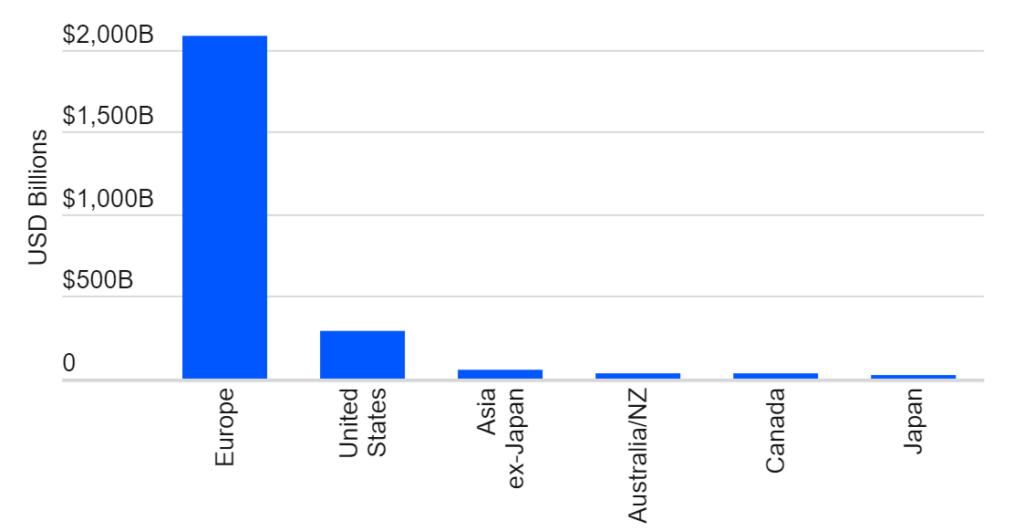

Global ESG fund assets in 2022

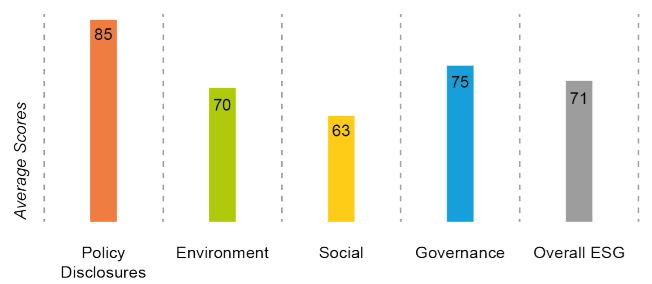

Average score of Indian companies on ESG factors

Consumer and investor activism has emerged as a powerful force in pushing companies towards more sustainable and ethical practices. Activists can influence corporate behaviour by demanding greater transparency, accountability, and commitment to ESG principles. This pressure can lead to tangible changes in corporate strategies, including increased investment in sustainable technologies, improved labour practices, and enhanced corporate governance. Highlighting the role of activism, we can underscore the potential for individuals and collective groups to drive systemic change, complementing the efforts of ESG investing.

The marketing of ESG funds often suggests that they contribute significantly to environmental and social objectives. However, the reality is that most ESG investments are in secondary markets, meaning they buy and sell existing shares rather than funding new environmental or social initiatives. This secondary trading does little to directly finance green technologies or social projects. The actual impact, or additionality, of these investments—meaning the extent to which they enable outcomes that would not have occurred otherwise—is questionable. For example, purchasing shares in a green energy company on the secondary market does not provide that company with new capital to expand its operations or innovate.

Financial performance and ESG investing

The belief that ESG investing can lead to superior financial returns is another contentious point. While many studies show a positive correlation between high ESG ratings and financial performance, establishing a causal link is more complex. The performance of ESG investments often mirrors broader market trends, and when adjusted for factors like company size, growth, and profitability, the supposed ESG premium diminishes. Moreover, the additional fees associated with ESG funds raise questions about their value proposition, especially when these funds closely track conventional benchmarks like Sensex and Nifty.

ESG investing’s popularity has increased pressure on regulators to mandate more comprehensive sustainability reporting and clarify what constitutes a genuine ESG investment. However, progress is slow, and the current regulatory system remains a patchwork of voluntary guidelines and inconsistent reporting standards. The regulatory ambiguity has allowed some market players to engage in greenwashing, where they exaggerate their ESG credentials to attract investment without making significant environmental or social contributions.

The effectiveness of ESG investing is also hampered by the lack of global cooperation and standardised frameworks. Environmental and social challenges are global in nature and require coordinated efforts across borders. The current landscape of ESG investing is marked by disparate standards, metrics, and reporting practices, making it difficult to compare and evaluate ESG performance across different regions and sectors. Advancing global cooperation to establish universal ESG standards and principles could enhance the consistency and comparability of ESG data, thereby improving the credibility and impact of ESG investing.

The way ahead

Recognising that ESG investing is not a silver bullet for global sustainability issues is the first step. While ESG metrics can provide valuable insights into a company’s risk management and long-term prospects, they should not be mistaken for direct measures of environmental or social impact.

Regulatory bodies and investors must demand greater transparency and consistency in ESG reporting and ratings. Additionally, to truly drive change, investments must be channelled into initiatives that directly contribute to sustainability goals, such as renewable energy projects, sustainable agriculture, and social enterprises.

Understanding ESG investing is crucial, but should not be aimed at dismissing the value of ESG considerations – it is about recognising their limitations and pushing for a more integrated and impactful approach to investing in a sustainable future. The progress towards a sustainable world is complex and requires more than just reshuffling investment portfolios—it demands concerted action, innovation, and a commitment to real change.