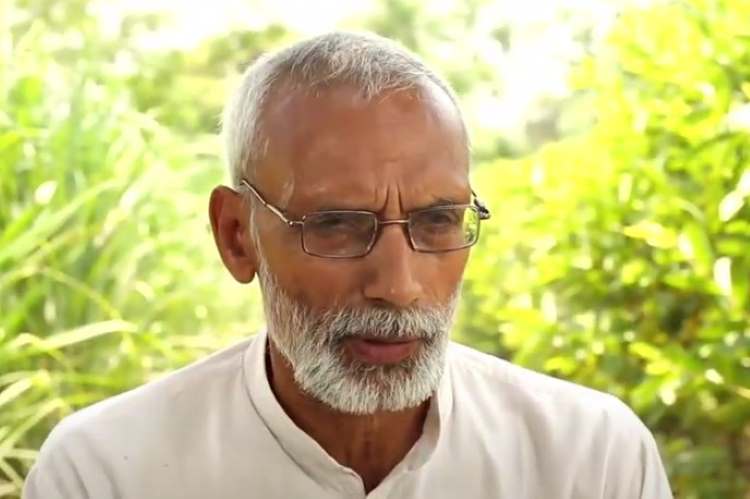

Farmer scientist Dr Bharat Bhushan Tyagi, a Padmashree awardee for his extensive work in agriculture, explains the complexities of policy making and the transformative potential of farmer-centric initiatives in this interview. He underscores the necessity of a unified policy approach that encompasses the vital aspects of nature, economy, nutrition, health, environment, and resource conservation. Dr Tyagi is worried about the lack of cohesive action among different government departments. Edited excerpts of his interaction with Yatish Rajawat, CEO, Centre for Innovation in Public Policy (CIPP).

We are fortunate to have with us Dr Bharat Bhushan Tyagi who has practiced and taught agriculture for more than 30 years. Our first question to you Dr Tyagi is how diverse are the novel methods such as organic farming, natural farming, regenerated farming, multi-cropping, and multi-layer farming.

There is a lack of clarity that can lead to widespread confusion while planning for the future. We explored the agricultural economy in 1987 when we were practicing modern farming. It became clear that all farming inputs come from the market. The means of selling produce, determining prices, processing, branding, packaging, and distributing are all market-driven.

We found that farming is susceptible to economic imbalance. There were fears that if farmers continued in this manner, it would cause significant harm to both the land and human health. In our search for alternative methods, we discovered living farming, organic farming, natural farming, cow-based farming, agnihotra, constellation agriculture, bio-dynamic farming, and more.

After experimenting with these methods, we realised they were simply different ways to reduce farmers’ production costs and escape from chemicals. I spent years debating which method to adopt. By 1997, we began to realise that these were all just methods, and there’s a huge difference between understanding and methods.

READ I Monsoon delay could impact rural consumption, economic growth

But can’t a system be established? A farmer can adopt a method or system according to their needs. We can call this traditional farming. There’s a paramparik kheti scheme which suggests farming should be done as it was done 200-250 years ago.

This brings about another contradiction. Reflecting on old farming methods raises several questions. Farming of the past was geared towards the family, whereas today’s farming is heavily influenced by societal factors. Now, farming also carries the significant responsibility of maintaining the economic balance. In this context, we don’t refer to old farming as paramparik kheti.

Paramparik kheti refers to practices that can be passed down and accepted by future generations. How do we maintain soil health? How do we preserve the seed tradition of trees and plants? How do we continue the lineage of animals and birds? These aren’t just methods; they form the basis of policies. The policies lie within the context of a system. It’s a natural production system where each participant has a defined role where the behaviour of the units is set. All creatures and plants on earth coexist without conflict. We fail to see the system of nature. If we genuinely want to effect significant change, we must focus our research on the system of nature.

We cannot completely detach from the market since we must sell our produce. Isn’t that the essence of family-centered farming, where you produce for your own family? The market isn’t inherently detrimental, but we must strive to achieve balance within it.

You’ve perfectly echoed my sentiments. My argument is that while we continue to operate within the market, we must also maintain a balance with nature’s system.

Can you tell me what policies the government has implemented to maintain this balance between the market and nature, and how these have impacted or not impacted the situation on the ground?

The most significant initiative the government has taken is its commitment to augment farmers’ income. The government has identified a natural imbalance, an economic imbalance, and a production imbalance. Furthermore, there’s been a societal imbalance with farming not being perceived positively. The government looks to rectify these issues in a manner that not only enhances the farmers’ income but also elevates the esteem of farming and ensures its economic stability. Policy decisions have been made to address this balance.

When scientists undertake research, they first study the system. They are introduced to a western or industrial agriculture system, yet the system of natural farming is often overlooked. Is this a flaw in our approach?

No, the issue cropped up after the green revolution. The surge in production and the euphoria had a lasting impact. A victory, once achieved, tends to linger. Many researchers have come to realise that the soil has been depleted and the environment adversely affected. The Indian Agricultural Research Institute is now grappling with the concepts of carbon credits and natural farming. There are indications of change, but progress is slow. This sluggishness can be attributed to a lack of unified dialogue.

Everyone champions their own method as superior which only fuels discord. The pressing need is to establish nationwide standards for organic farming. When natural farming emerged, standards for it should have been set along with international standards. This is a monumental task. There is a need to develop a universal standard applicable to natural, organic, or any other emerging methods, so that policies can be formulated, quality standards can be set, and every method can find success.

Are you suggesting that regardless of the system, technique, or approach, the focus should be on maintaining a balance with nature? Can this be done irrespective of concerns about research, education, the MSP policy, or other incentives?

Yes, my point is that we need a common dialogue across all systems related to the agriculture sector in this country at all levels. Have we been able to define a policy? Do we have a unified agricultural plan to maintain production balance? Have we been able to provide a robust programme for farmers at the state government level? We definitely have small schemes, we allocate budgets. There’s activity across the country, but what we lack is cohesive policy.

Let us discuss the multi-layered or multi-crop farming method that you’ve been practicing and advocating for many years. How can we grow different crops and trees together to make the best use of land, water, and sun, without excessive use of chemicals?

True that many people are caught up in the specifics of terminology. I have focused on understanding the laws of nature. I wouldn’t give it a specific name and claim ownership over it. I have observed, understood, and practiced a system which has been broken down into three steps: understanding, learning, and implementing. We study and apply these principles, and explain them to farmers who readily grasp these natural laws. For example, what governs soil fertility? Does the soil produce its own nutrients, or do we need to add them? Should I create compost, or understand how the soil fertilises itself?

The primary insight is that the soil’s fertility and richness can’t be maintained with a single crop, as diversity is a law of nature. The soil requires a variety of nutrients, which it acquires through the roots and remains of plants. The by-products of plants become the soil’s nourishment. Nationally, we need to avoid imposing methods and costs on farmers from a purely business perspective. Remember, maximum yield can’t be obtained from a single crop; to increase production, we need to diversify.

The model implemented in your farm has been thoughtfully designed. But every farmer will have to tailor this diversification or multicropping model to their own needs. This model is ideal for small-scale farmers with one to five acres. What incentives could the government provide to make this model more popular?

A: We really need to modify our national programmes. With the number of small and marginal farmers exceeding 80% of the total, we need to change our farming machinery, production processes, and all methods regarding which seeds are used where, in which season, which machinery is used, and what resources are necessary. If we want to adopt a cluster approach, we must consider how to reduce costs and foster cooperation. We need a nationwide policy shift that takes us from inputs to production and post-harvest management, recognising that large machines are not necessary for small farmers.

For instance, a big tractor… it can’t even turn in a one-acre field. It needs at least five to 10 acres for a complete rotation. Why are these tractors being manufactured and promoted when 90% of farmers can’t fully utilise them?

The government has taken note of this. The present administration has done commendable work through the farm machinery bank and custom hiring centers, so that small farmers can also access machinery including post-harvest management machines. However, my request to the government is to give priority to smaller machines as well. In areas with small clusters, the Farm Machinery Bank should consider the farmers’ affordability. How large is the cluster? Which machine should they receive? How will the machine be used? What kind of pests are present? We need to keep all these factors in mind.

The national budget that we allocate to farming is substantial. Not only can we get more done with this budget, but we can also shift from input to post-harvest management. This is also the government’s intention. Hence, if we have a robust agricultural policy, the budget can be used more effectively.

The takeaway from today’s discussion is the need for an agricultural policy that focuses on small farm multi-cropping in harmony with nature. So far, our policies have been centered on either production or single-crop systems. All our research centers are crop-specific. We have institutes for millet research, potato research, and so on. The Indian Agricultural Research Institute is also part of this structure, but even it doesn’t primarily focus on natural systems. Instead, it leans more towards industrialisation.

You have hit the nail on the head. Our current approach is heavily skewed towards business and markets, with little room for the natural order. We argue that markets will always exist, but we need to incorporate nature’s system into them. For example, this year has been declared the year of millet, meaning millet will be the main topic of discussion.

But how can we integrate millet into an integrated crop management system in the sugarcane belt? How can we incorporate millet into organic agriculture? And how can we introduce millet to the mountains? If we don’t consider all these aspects and our farming system is incomplete, we will swing from focusing on millet to potatoes to sugarcane without a comprehensive plan.

It seems that for a century, we’ve been chasing specific crops and their genetic advancements. Recently, the focus has been shifted to nano chemicals which are expected to boost farmers’ income or reduce costs. Could you elaborate on the impact of nano chemicals on our land?

This is a serious topic that needs thorough research. When we initiate a transformation, the effects within this shift intensify rapidly as we move from large to minute quantities. Nature doesn’t operate this way. This is a concern also for corporate traders. IFFCO first implemented nano, and I was at that programme. It seems we are shifting from large to small quantities, but the consequences of this need to be understood.

Another contentious point is our attempt to systemise farmers. Much like the corporate structure in the economic world, we’ve tried to establish Farmer Producer Organisations (FPOs) over the past decade. Despite thousands of FPOs being created and dissolved every year, NABARD continues to propose new FPOs. What is the real impact of this cycle of FPOs at the grassroots level?

It is indeed a great programme. However, just as we failed to provide proper agricultural training to farmers and kept promoting our own methods, it seems we’re repeating this with Farmer Producer Companies. I believe our focus shouldn’t be on mistakes but rather on opportunities. It was critical to enhance the capabilities of all business organisations in the country. While their economic valuation was done, we didn’t assess them on their capabilities – do they understand society? How will farmers work together? Can they resist political pressure?

The final question. The Union government outlines numerous agricultural policies. These are implemented through a cascading system, from the state government, to the district level, and finally to the panchayat. In light of this, what changes, absences, or impacts have you observed in these policies or their systems over the last 50 years?

This question ties into a comprehensive overview of agriculture. We embraced the Green Revolution due to specific circumstances. Today, however, those circumstances have evolved, which necessitates us to proceed with an updated approach. Our primary apparatus for this involves both the Union and state governments. The Union government is responsible for establishing policy uniformity, ensuring balances in nature, economy, nutrition, health, environment, earth, and water. The question is, how can we guarantee the appropriate utilisation and preservation of these elements for future generations. That’s the underlying principle of agricultural policy.

The state governments are tasked with policy implementation. They look to maintain a production equilibrium in a holistic agricultural work plan. But there’s a pervasive issue; each department within these state governments operates independently. There’s no integration. Hence, state governments should adhere to a unified agricultural work plan in alignment with the national agricultural policy. This strategy would ensure both production balance and quality.

Maintaining a production balance helps us secure our food supply and prepare for national and international exports. Currently, farmers cultivate crops based on market whims. If a crop’s price surges, they plant it; if it drops, they abandon it. No government can control this production balance at the farmer level. Therefore, it’s crucial to foster coordination between central and state governments to establish a system that maintains a regulated production balance.

We must tie the budget to policy definitions to empower farmers, instead of enticing them with grants. If we view these grants as incentives, then the government should focus more on developing their basic infrastructure. I applaud the government for investing heavily in agricultural infrastructure and in the fund for successful farmer producer companies. If these systems become successful and a model is established at a village level, the future of agriculture will take a new turn.

Watch the full interview with Dr Bharat Bhushan Tyagi.