Pension reforms have been a hot topic for debate in India for a long period. An article published in the RBI’s September Bulletin throws light on the fiscal implications of returning to the Old Pension Scheme, which many Indian states are now contemplating.

At the outset, it is crucial to understand why the National Pension System (NPS) was introduced. The older Defined Benefit (DB) system, of which the OPS was a part, was not sustainable in the long term. The pensions under this scheme were paid from the current revenue of the government, creating a heavy financial burden as the life expectancy of citizens increased. With global life expectancy on the rise, it is projected that by 2050, the percentage of the global population aged 65 years or above will increase by 6%. Such statistics suggest the unsustainability of the OPS in the long run.

The NPS, introduced in 2004, was a defined contribution scheme that aimed to replace the burdensome OPS. It ensured that both the employee and the employer contribute to the pension, which is then invested to create a corpus for the employee’s retirement. In essence, NPS was introduced to relieve the government of excessive future pension liabilities.

READ I Can IMEC counter China’s belt and road initiative

Old pension scheme on comeback trail

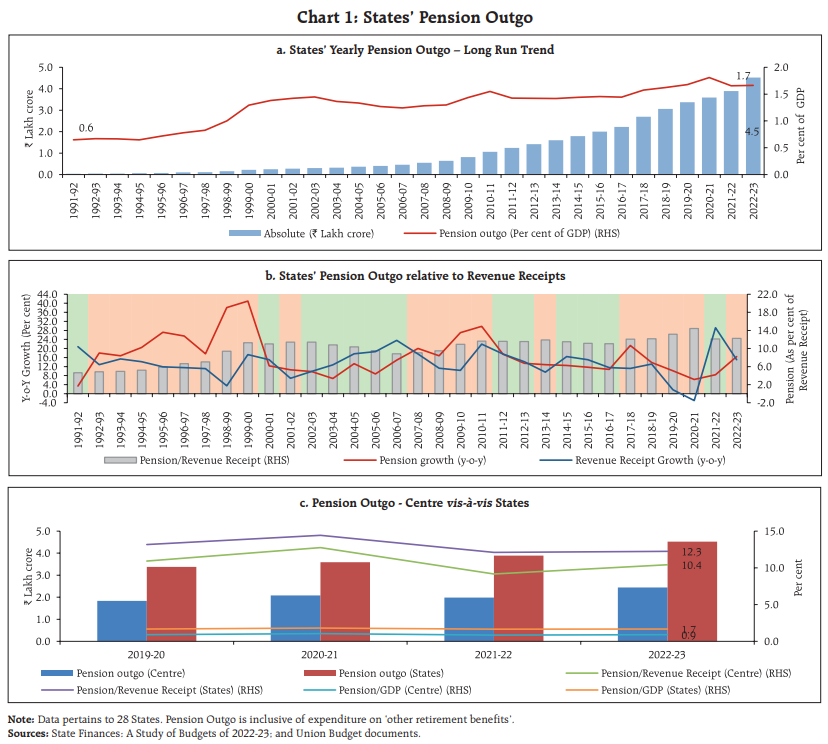

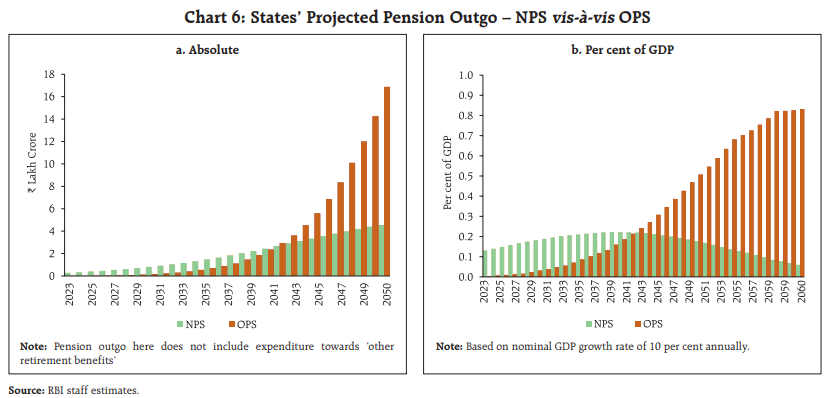

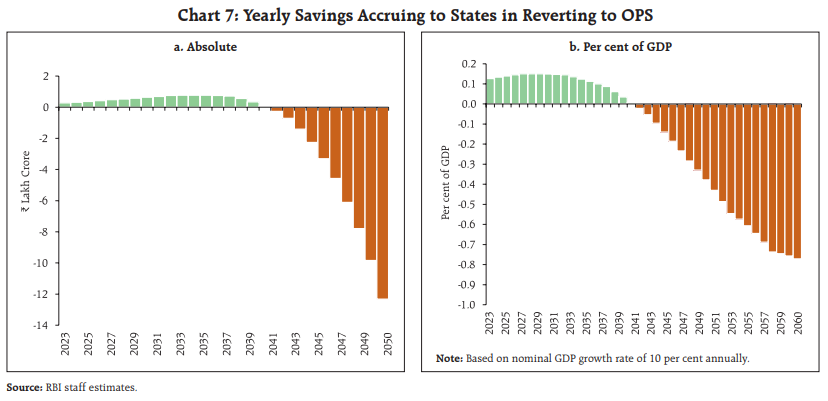

Recently, states like Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Punjab, and Himachal Pradesh have contemplated reverting to the OPS. While this may provide short-term fiscal relief by eliminating the current NPS contributions, the long-term implications are daunting. The research estimates that the cumulative fiscal burden of the OPS could soar to 4.5 times that of the NPS. By 2060, this could translate to an additional burden of 0.9% of GDP annually. These numbers are not mere statistics; they represent the possible fiscal derailment that could jeopardise the economic stability of states.

The trajectory of the OPS fiscal burden is further aggravated by projected increases in life expectancy and moderations in GDP growth. For instance, even a 1% fall in the average growth rate could amplify the outgo from 0.9% to a whopping 1.3% of the GDP by early 2060s.

What is even more worrying is the variation of this pension burden across states. States like Bihar, Kerala, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, and West Bengal already exceed a pension outgo of 25% of their own revenue receipts. If these states decide to revert to the OPS, their fiscal burden will inevitably skyrocket, affecting their economic growth and stability.

Furthermore, a considerable pension outgo could force states to curtail their capital expenditures, which could stunt long-term economic growth prospects. As pensions are committed expenditures, they remain largely unaffected by economic cycles, making it even more critical for states to make judicious decisions regarding pension schemes.

The NPS was introduced to ensure fiscal stability and sustainability. By reverting to the OPS, states might be stepping backward, jeopardising their fiscal health and, in the process, the well-being of their citizens. While the allure of short-term gains is hard to resist, states must view pension reforms in light of long-term implications. The numbers speak for themselves, and if states choose the path of immediate relief over future sustainability, they might be saddling themselves with insurmountable economic challenges in the decades to come.

The pension landscape in India underwent a significant transformation in 2004 with the introduction of the National Pension System (NPS), a response to the escalating fiscal pressures from the Old Pension Scheme (OPS). This was, in essence, a move from an unfunded ‘pay-as-you-go’ system to a more sustainable, defined contribution system, which aligned with global best practices and responded to demographic challenges and macroeconomic demands.

The fiscal burden of OPS

The recent trend of certain states reverting to the OPS poses significant risks, both in the immediate and long-term fiscal horizons. The article, written by Rachit Solanki, Somnath Sharma, RK Sinha, Samir Ranjan Behera, and Atri Mukherjee, offers some compelling insights into these risks:

Immediate gains but long-term fiscal stresses: While there is an evident immediate reduction in states’ pension expenses upon reverting to OPS, this is highly deceptive. Such states would be encumbering themselves with future unfunded pension liabilities that could escalate up to 4.5 times the fiscal burden compared to the NPS. Simply put, today’s savings may translate into tomorrow’s massive debts.

Projected growth scenarios: Any slight moderation in GDP growth can drastically raise the financial burden on states. With an assumed nominal GDP growth of 10%, the pension outgo could be 0.9% of the GDP by 2060. A fall in this growth rate by even 1-2 percentage points could skyrocket this outgo to 1.3% to 1.9% of the GDP. The looming uncertainty of global and domestic economic cycles makes this a real concern.

Understanding the cumulative burden: The ratio of the present value of total OPS burden to the present value of total NPS burden starkly highlights the imprudence of switching back to OPS. An average increase of around 4.5 times in the overall pension burden over six decades is an onerous fiscal strain, raising questions about sustainability and prudent fiscal management.

Demographic concerns: With global life expectancy projected to grow and the percentage of senior citizens in the population expected to rise, the unfunded OPS would undeniably lead to escalating public expenditure. A growing aging population implies that more individuals will draw from the pension system, thereby magnifying the financial implications for states reverting to OPS.

Impact on broader macroeconomic health: The temptation to revert to the OPS, as suggested by the study, has the potential to negatively influence various macroeconomic parameters, including labour markets, savings and investments, and capital market development. States taking this route may inadvertently be undermining their medium-term economic outlook.

Strategic national implications: Pensions, though seen as a state subject, have broader national implications. Unfunded pension liabilities in multiple states could have ripple effects on national fiscal health, credit ratings, and investor perceptions, possibly hindering national growth prospects.

The decision by some states to revert to the OPS from the NPS is fraught with substantial fiscal implications. It is crucial for policymakers to weigh the short-term gains against the profound long-term financial commitments. Sustainable fiscal management is not just about immediate budgets but ensuring that states remain resilient, economically robust, and equipped to handle future challenges. The adoption of NPS was a step forward in that direction; reverting to OPS could be many steps backward.