India’s Unified Payment Interface has come a long way since Google recommended it to the US Federal Reserve in 2019. Payment apps using UPI are already accepted in Bhutan, Singapore and UAE, and several other countries including France are set to link up with it. The interface’s unique success is taking it in an interesting direction — one that will make it adaptable and useful across the world.

Going by the RBI’s latest moves, the UPI architecture will become a global payment gateway. Inter-currency exchange and settlement requires central bank digital currencies (CBDC), at least for global trade and wholesale transactions. On September 20, RBI Governor Shaktikanta Das, flanked by NPCI advisor Nandan Nilekani and chairman Biswamohan Mahapatra, announced the three building blocks for making UPI adaptable across the world.

Speaking at the Global Fintech Fest 2022, Das launched three key initiatives — RuPay Credit Card, UPI LITE, and Bharat BillPay cross-border bill payments system. RuPay Credit Card on UPI opens up an interesting opportunity for Indian banks to offer credit cards in all the counties that deploy UPI. It will make space for Indian banks to take their credit disbursement global.

READ I Global payments: Can India present UPI as alternative to SWIFT

UPI going global

A number of countries are contemplating or already deploying UPI. If Indian banks find it difficult to offer RuPay credit cards globally, Indian fintechs can move into this space. CRED and others might be thinking about it already. In a way, a digital infrastructure is being created for them. This is why rapid deployment of UPI across the world should lead to a redefinition of its purpose from just being digital public good to a digital public infrastructure.

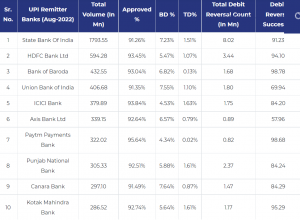

Top 10 UPI parner banks

The deployment of RuPay credit cards will facilitate micro payments across the world. This would change the merchant to buyer payment interface, not only in Asia but also in Africa. This will also reduce the cost of transaction across the credit-starved societies of Asia and Africa. This will offer National Payments Corporation of India, which runs UPI, an enormous global fintech opportunity. This is where UPI lite would play a major role as it needs less digital space and low bandwidth.

All these developments bring us to a critical decision point — something that the RBI triggered with a paper on August 17 on the introduction of the charges on UPI transactions. The discussion paper by RBI provides a transparent approach towards an issue of public interest. This is a better way of handling a contentious policy issue that has implications beyond UPI and the Indian banking industry.

READ I Interest rates: RBI should go easy on monetary tightening

A case for keeping UPI free

The debate is around whether UPI should charge a fee for transactions on its platform. This not only defines the most successful digital public good, but will also affect the contours of other DPGs and digital public infrastructure. The launch of the three products by the RBI governor on September 20 also has a bearing on the charges, not only in India but also in countries that propose to adopt UPI.

A public park is a public good as the state does not charge directly for using it. Local or national taxes may be used for making the park, but it remains free to use for all people, not just the taxpayers or citizens. Similarly, UPI is a public good. NPCI, the organisation that owns it, should not charge a fee from users. It does not cost NPCI anything to make this public good as it was built by volunteers.

There is a cost of hosting and maintaining it, but it is a pittance compared with the savings it offers to the economy. By reducing the cost of transactions to zero, it has been able to bring in many more transactions into its fold. Thus, it doesn’t make sense to change these transactions.

This brings us to another question. Who wants to charge fees for UPI transactions? Is it NPCI, or the merchants, payment wallets, credit cards and banks that want to levy a fee for transactions. These are all service providers and if they are asking NPCI/ RBI that they want to charge these transactions, is it not odd? They did not pay for building UPI infrastructure directly. They can justify that their taxes funded it, but that analogy is weak from the public goods perspective.

The only justification for a charge is if value addition is done in the process of the transaction. Certain payment wallets charge for say school fees payment, utility payments, and others. This is done by companies that are monopoly providers of the service. This is fine to the extent that a facilitation or service exists over and above the UPI transaction being provided.

For instance, an ice cream vendor inside a park can charge for the ice cream he is selling but should not charge a premium to consumers for selling in a public park. UPI cannot be made into a toll highway where a charge is levied for usage.

Even a small flat charge will discourage small transactions and will affect small merchants and micro entrepreneurs who are expected to benefit the most from this DPG. An ad-valorem charge will also ultimately affect the volume of transactions on the system and that is not the goal of the DPG.

UPI is a global success story and it should not be derailed by global lobbies that have a vested interest in this platform becoming a private product comparable with their own platforms. There can be a paid parking for cars near a public park, similarly if there is a value addition on any end of transaction that can be charged by the service provider. But the charge should be transparent.

If credit is provided to the merchant or consumer, it can be charged. But it should not be opaque, or merged into the pricing of the transaction itself. This is what UPI can bring to the global payment industry.

The lobbies are aware that UPI can be a gamechanger in the global payments industry. The FED wants to grow up to be a UPI. The UAE, Brazil and Spain are all trying to emulate or recreate UPI. The RBI must respect that UPI is now influencing the global payment industry and this is good for all stakeholders — not just the consumers, but also banks and merchants, globally. The biggest gain for India in the process would be the soft power it achieves in the global payments industry.

(K Yatish Rajawat works at Centre for Innovation in Public Policy, a Delhi-based think tank studying public policy and economic growth. Views expressed are personal.)