The Union ministry for health and family welfare recently published a new drugs Bill- New Drugs, Cosmetics and Medical Devices Bill, to replace the colonial-era Drugs and Cosmetics Act, 1940. The legislation received flak from the medical fraternity and analysts who criticised the lax new rules. While the new Bill retains the spirit of the old legislation, it also contains some new provisions that make it easier to pass clinical tests as it presumes that a drug will work even if it fails on certain quality parameters.

The Bill follows the trend of decriminalisation of offences observed in other recent legislation brought in by the Narendra Modi-led NDA government in an effort to improve the ease of doing business in the country.

ALSO READ: Merchant Shipping Act: Govt to replace imprisonment provisions with penal fines

Provisions of the new drugs bill

The draft legislation proposes new definitions for clinical trials, over-the-counter drugs, manufacturers, medical devices, and new drugs, while proposing regulation of online pharmacies and medical devices. It proposes imprisonment and compensations in the cases of injury or death during clinical trials. The proposed Bill was written by a drafting committee of eight bureaucrats led by the Drug Controller General of India (DCGI).

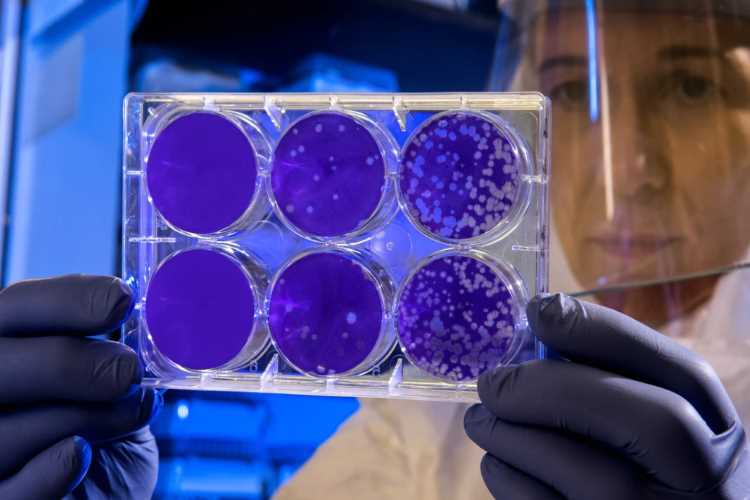

The watered-down provisions in the new Bill may impact the quality of drugs in India which is anyway infamous for lax regulation.

Historically, drugs failing quality tests made the manufacturer liable for minimum imprisonment of one year and maximum imprisonment of two years and fines up to Rs 20,000 with some exceptions. The rules have been tight for simple reasons — one cannot play with health of citizens unlike the case with other products. Quality issues in drug manufacturing are sure to have direct implications on the health of citizens. Thus, the same attracts criminal punishment.

The new bill, however, has accommodated the pharmaceutical industry’s demand to decriminalise some of the offences under the existing law.

The government has also proposed the reduction in punishment for NSQ drugs. NSQ drugs are those which fail quality tests due to any of the 43 defects listed in the fourth schedule of the Bill. For such defects, manufacturers are liable for lower imprisonment of one year and a fine of Rs 2 lakh, while for defects that do not fall within the fourth schedule, the manufacturer is liable for a tougher punishment of up to two years imprisonment and a fine of Rs 5 lakh.

Other than softening of various punishments, the definition of clinical trials under the proposed law is far too vague, according to sector analysts. They say that the new definition deviates from the guidelines set by the World Health Organisation (WHO).

ALSO READ: Climate change: India sets tough emission targets for 2030

Among the more serious consequences of the new Bill is lower punishments for fourth schedule defects is also likely to serve the interests of the pharmaceutical industry as it allows for the compounding of a class of offences. Compounding allows prosecuting of the drug controller to waive a trial, and prison term if the accused pharmaceutical company agrees to pay the fine. The section 58 of the Bill gives the government the power to expand the list of exceptions in the fourth schedule. The financial muscle of the pharmaceutical industry may lead to inclusion of more exemptions over the existing 43, making the new Bill a dream-come-true for the pharma industry.

For instance, the fourth schedule lists defects including the presence of “particulate contamination/ foreign matter” and “heavy metals”. The new Bill says even if a drug is found to be contaminated with glass particles, fungus or heavy metals, the manufacturer will get reduced or no prison term. Such provisions make the new Bill heavily loaded in favour of the pharma industry.

Instead of taking a route that suits the interests of businesses, the government must find a balance between the interests of the pharma industry and the provisions needed to ensure the well-being of the common people. This becomes especially pertinent in a country where laws are not stringent, and even if they are, the execution has never been practical. The policymakers must also take stakeholders in confidence before finalising the bill, instead of giving in to demands of the pharma business.