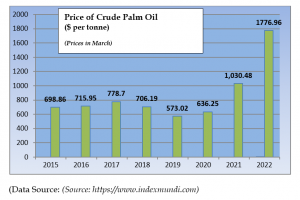

Soaring palm oil prices trigger inflation spiral: Indonesia’s ban on palm oil exports sent shock waves across importing countries, already struggling to contain runaway food prices. The world is grappling with the shortage of wheat and sunflower oil, caused by disruptions in supply from Russia and Ukraine. The largest producer of palm oil in the world announced the ban in March 2022 without any time limit to address the ongoing shortage and the resultant price rise in the domestic market.

It was subsequently clarified by the Indonesian authorities that the export ban would be limited to refined, bleached, and deodorized (RBD) palmolein used for frying purposes and not crude palm oil. It is feared that the decision could have serious consequences in terms of price and supply since palm oil finds applications in a range of products from cooking oil to chocolates to cosmetics. In March 2022, the Indonesian government had announced an increase the limit of domestic sales from 20% to 30%, which led to a fall in export volumes.

READ I Interest rate hike: Can RBI avert a hard landing

Rising demand for palm oil

The surge in demand for vegetable oils is the result of rising requirements from both food and industrial markets. Global demand for palm oil, soya oil, olive oil, canola, sunflower, and coconut oil have been rising due to growing population, rising income in developing countries, growth of food processing and cosmetic industries. Palm oil, in particular, has varied applications and is used in a range of products:

- Food Products: Around 68% is used in foods ranging from margarine to chocolate, pizzas, bread, and cooking oils;

- Industrial use: 27% is used in the production of soaps, detergents, cosmetics, and cleaning agents;

- Bioenergy: the balance 5% is used as a component of biofuels for transportation purposes.

In the food segment, palm oil has become the most widely consumed vegetable oil in the world with a share of 36% of the total global consumption. One of the reasons for its widespread acceptance in the last 50 years is its high productivity. By using less than 9% of croplands devoted to oilseed production it produces 36% of total vegetable oil produced globally.

Its high productivity can also be judged by the fact that it needs approximately 3%, 12%, and 25% of the land area required for cultivation to produce the same amount of oil from sesame seed oil, sunflower oil, and olive oil. Thus, apart from wider applications, the use of palm oil helps us in saving the land used for the cultivation of oilseeds. If switching over to alternative oil crop cultivation is planned it would mean the use of more farmland, which comes with an environmental cost as it would lead to deforestation.

READ I Timely action on inflation needed to avert hard landing

The global production of vegetable oils which was at 90.5 million tonne in 2000 reached 213 million tonne in 2021 (Source: statista.com) whereas the production of palm oil has increased from 22 million tonne to 70 million tonne in the same period, thus outpacing the growth rate in the overall vegetable oil sector. Indonesia and Malaysia dominate the global market with a combined share of 84% in the production of palm oil with an individual share of 57% and 27% respectively in global production.

On the consumer side, besides Indonesia, the Republic of China, the European Union (EU), and India are the largest consumers of palm oil. A market report on the global vegetable oil industry by Report Linker has forecasted that while the market for vegetable oil will grow at a CAGR of 4.4% till 2026, the expected CAGR in palm oil segment would be higher at 5.2%.

Dependence on imported edible oil

India is facing high retail inflation rate that touched 6.95% in March due to high prices of petrol and diesel. It is likely to be affected in the coming months by the increase in palm oil prices. According to The Solvent Extractors Association of India (SEA), the country consumes around 13% of the global production of palm oil and the annual local production of CPO is only 0.3 million tonne while the imports are at 7.5 million tonnes/year.

The country has been meeting 80% of its requirement for refined palm oil and up to 70% of the CPO requirements from Indonesia in recent years. Thus, the increase in the price of Indonesian palm oil is likely reflect across the FMCG sector. The increasing cost of imported CPO in the last two years was visible in the import bill. Despite a fall of 47% in the imported quantity of palm oil from Indonesia in 2021-22 (11 months) compared with 2020-21, the corresponding fall in the import bill was only 16.5%.

READ I Easing of public debt burden will cause economic disruption

Malaysia increased the palm oil exports to India in 2021-22 (11 months) by around 4.6%. This resulted in an increase in cost by 64%. The price of Malaysian CPO too increased in the last two years due to labour shortage as it is heavily dependent on foreign labour from Indonesia and Bangladesh which got stuck due to Covid restrictions. The value of imported CPO and refined palm oil in 2021-22 is expected to exceed $10 billion compared with $5.67 billion in 2020-21, an increase of 77%.

With an import dependency of more than 60% in the vegetable oil sector, the surge in the import bill is likely to continue. Even before the Indonesian ban, the global cooking oil prices have been rising since the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, causing procurement and transportation issues as well as labour shortages. New mandates by countries for increasing the use of vegetable oil in biofuel also add to the cost. The weather in the major edible oil-producing countries also played the spoilsport, adding to the demand-supply imbalances. Currently, the landed cost of imported CPO, soya oil, and sunflower oil is stated to be around $1,900 per tonne, $1,998 per tonne, and $2,100 per tonne.

Domestic production not in sync with global consumption

Despite impressive growth in domestic oilseeds production in India, it is not able to match the galloping per capita consumption which has grown from 3 kg in 1950 to 19.7 kg in 2020-21, driven by the increasing population and income. The supply crunch and the subsequent price rise is not limited to palm oil, but also in other edible oils like sunflower oil and soya oil,

Sunflower Oil: Like CPO, India is the largest importer of sunflower oil with a share of 23.5% in the global import of around $2.1 billion. The supply of this commodity has witnessed uncertainty due to the war between Ukraine and Russia pushing its price upwards. These two countries together supply about 90% of the total import of sunflower oil into India with Ukraine having a larger share of 73%. In the case of crude sunflower oil also, imports into India during the 2021-22(11 months) witnessed a substantial increase of 27%, despite an 18% fall in quantity.

Soya oil: India produced about 1.7 million tonne of soybean oil in 2021 out of a total of 59.4 million tonne global production. Although a major producer of soybeans, the country meets 25% of its annual requirements through imports. In this sector also, a substantial price rise in the international markets was seen as a result of the loss of production of soybean production in Argentina and Brazil due to drought and frost. Argentina, the largest exporter of soya oil, had to deal with a nationwide protest of truckers who carry 85% of their crops and products.

Then, speculation of a likely increase in export tariff by the Argentinean government from 31% and the attempt by the Chinese government to stockpile soya oil fuelled the international price. As per data available with the department of commerce, in the 11 months of 2021-22, the import bill of crude soya oil increased by 57% despite a reduction in import quantity by 4.5% compared to the 12 months of the previous year.

In such a scenario, the export ban order by the Indonesian government is likely to cause a huge imbalance in the demand-supply position and cost increase across the entire range of edible oils leading to an enhanced foreign exchange burden on India for import. The table below shows the trend as seen during 2021-22 compared to preceding years:

Government initiatives

To reduce the impact of increased international prices, the government in October 2021 took initiatives like cut in import duty on soybeans oil, sunflower oil, and palm oil (a reduction from 2.5% to zero), removal of refined palm oil from restricted category to “free” category under foreign trade policy, imposed stock limits on edible oils and oilseeds to prevent hoarding, and suspended futures trading on mustard oil and oilseeds on the NCDEX to help moderate the domestic retail price of edible oil which nearly doubled during the preceding period.

In February this year, the government brought down the effective duty on crude palm oil import to 5.5% from 8.25% by reducing the agri infra development cess to 5% from 7.5% as a measure to control cooking oil prices and support domestic processing companies. However, these short-term measures are expected to have only limited impact.

National mission on edible oils

Domestic edible oil production has not been able to keep pace with the growth in consumption which has reached around 25 million tonnes per annum and the per capita consumption of 19 kg. The total domestic production of edible oil is around 12 million tonne only. This has resulted in India becoming the largest importer of vegetable oils in the world followed by China and the US. Of all the edible oils imported into India, the share of palm oil is the largest at 60 %, followed by soya and sunflower oil with a respective share of 25% and 12%.

To address the issue of increasing import bill, the government rolled out the national mission on edible oils – oil palm (NMEO-OP) in 2021. The scheme envisages increasing crude palm oil production by bringing additional land under palm plantations. The Rs 11,000 crore mission has the target to raise the domestic production of crude palm oil (CPO) from 0.27 lakh tonne in 2019-20 to 11.20 lakh tonne by 2025-26 and 28 lakh tonne by 2028-29.

The area under palm plantation is to be increased to 10 lakh hectares by 2025-26 from 3.5 lakh hectares as of 2019-20 . Under this mission, farmers who opt for palm oil cultivation will receive price assurance from the government which will hedge the farmers from price volatility.

It may be too early to assess the likely impact of the scheme on the availability of palm oil in the years to come. However, the NMEO-OP has very specific targets in the short and medium terms and is being monitored both at the central and state level. While the scheme offers incentives to encourage farmers to take up palm plantations to enhance domestic availability and reduce import dependency on palm oil, a more holistic approach based on a comprehensive policy for the development of the edible oil sectors is needed. Some of these issues/challenges not adequately covered under the scheme are being discussed here.

- Increasing plantation area for palm cultivation could result in clearing of forests and cutting trees as seen in Indonesia and Malaysia with serious environmental impact. In India, the focus areas identified for the implementation of the scheme include those from North-Eastern India. The deforestation risk in those environmentally sensitive areas for clearing areas for palm cultivation has to be closely monitored to ensure it is sustainable.

- A long-term plan should also look at and study the emerging changes in the consumption pattern of different edible oils with a focus on the habits of the young generations. In the last 50 years, the consumption pattern has seen a shift towards the palm, peanut, and sunflower oils vis-à-vis soya oil, though soya oil retains a good share in the global vegetable oil market. In the Indian context, olive oil consumption is considered healthy and its market in India has witnessed considerable growth in recent years due to a rise in health-conscious young consumers. It is reflected in the increasing value of imported olive oil and its different fractions in India from US$ 12.6 million in 2009-10 to US$ 286 million in 2021-22(11 months). In addition, enhanced disposable income of the middle-class has provided an upswing to the olive oil industry since apart from the food sector, it is also consumed by the personal care, pharmaceutical, and beverage industry.

- The productivity level of several oilseeds has not seen any substantial improvement over the years suggesting a need for dedicated application of technology. For example, in soybean farming, the productivity level in India is stagnated at around 1100 kg/hectares which is one-third of average productivity in the USA, Brazil, and Argentina, and 40% of the global average. Besides hesitation in the adoption of technology by farmers and the use of the certified seed, the other major reasons for low productivity are irrigation management and soil nutrients management. Proven technologies are available, but it does not reach the farmer.

- The use of genetically modified(GM) oilseeds is being debated in the country for quite some time and has the potential to increase the yield by 300-400%. An early decision to end uncertainties about the use of GM seeds would be in the overall interest of food security.

- The local refiners of edible oils have been complaining about the underutilization of their capacity by as much as 40%. India could also turn the Indonesian ban order into an opportunity by resorting to more imports of crude oil and thus increase the capacity utilization of installed domestic oil refining capacity.

- The per capita consumption of edible or vegetable oils in India has sharply gone up which could be attributed to the general enhancement in affordability. Some may see this piece of data as a positive signal for the economy. However, it is also known that excessive consumption of oil is not good for health. These oils contain fats, especially saturated fats, which are known to increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases.Studies have shown that an annual vegetable oil intake of 10.5kg per person p.a. is sufficient to meet the nutritional requirements of Indians while the per capita consumption has already exceeded 19 kg per person per annum. The excess oil consumption thus has both economic and health implications for the country. It is therefore desirable to reduce the consumption of vegetable oils by raising awareness among the consumers about healthy oil consumption habits, thus moderating the rising demand curve for the edible oils.

Krishna Kumar Sinha is an industrial policy and FDI expert based in New Delhi. His last assignment was as an industrial adviser in the department of industrial policy and promotion, DIPP, currently known as DPIIT, under the ministry of commerce and industry of the government of India.