India’s unemployment crisis: The Indian economy grew 8.5% in the second quarter of 2021-22, according to official data. The GDP growth rate for the quarter is higher than the 7.3% recorded in the corresponding period in the last financial year. This is clearly an indication of a recovery from the economic slowdown triggered by the Covid-19 pandemic, but the country’s workforce is in bad shape. The Periodic Labour Force Survey for the period October-December 2020 revealed a rise in own-account workers, helpers in household enterprises, self-employed people and casual labour.

Since the lockdown was announced, the share of own-account workers went up from 30.4% to 32.9%, household helpers from 5.1% to 5.6%, self-employed people from 38.3% to 39.3% and casual workers from 11.2% to 12.7%. The only category of employment that saw a fall is regular wage/salaried employees. Their share fell from 50.5% to 48.1%.

From the sectoral perspective, informal agriculture experienced a rise from 5.1% in 2020 to 5.9% in 2021 (as this urban employment survey shows, the share of agriculture is low). The secondary sector (mining, manufacturing, part of construction) also witnessed an increase, though relatively smaller, from 32.5% to 32.7%. Tertiary (services) sector, which has a larger presence of informal workers, witnessed a fall from 62.4% to 61.4%.

READ I Labour codes implementation to face delays as states struggle to frame rules

Informalisation of labour

These figures confirm the trend of informalisation of the labour force. Agriculture is the end option of the job-seekers who cannot be absorbed in the manufacturing and service sectors. There was a fall in the number of persons engaged in agriculture in absolute terms during the year 2009-12, but the trend could not be sustained beyond that.

The last annual PLFS of 2019-20 also showed the share of agriculture going up from 42.5% in 2018-19 to 45.6% in 2019-20, while manufacturing went down from 12.1% to 11.2%. A study by Azim Premji University shows that during the pandemic years of 20-21 informalisation increased and led to a severe decline in earnings for the majority of workers.

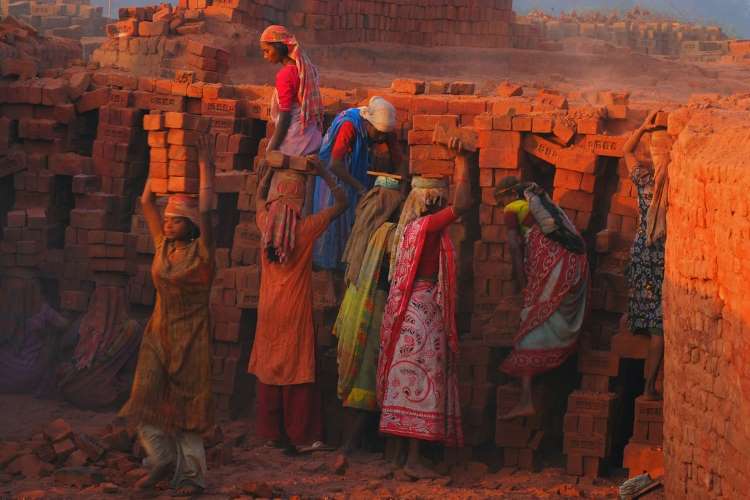

India has a high share of informal labour compared with the global average. About 90% of India’s workforce is informal. They do not have access to institutional social security. This share is 70% in emerging developing countries whereas in developed countries this share is 18%. India’s workers are also among the lowest-paid in all workers. In India, we have a phenomenon known as ‘working poor’, that is, people work but they remain poor.

READ I Post-Covid labour market needs policy intervention, income support for vulnerable sections

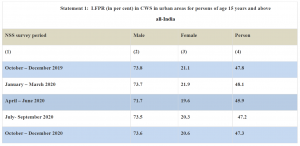

As for the working population, the latest NSO Survey (January-March 2021) puts labour force participation rate (LFPR) — which combines those working or seeking work in the age group 15-59 years of the population — at 47.5% in urban areas, down from 48.1% in January-March 2020 [pre-pandemic]. The annual PLFS of 2019-20 shows the overall LFPR at 40.1%. In comparison, the OECD average for 2020 (15 years and above) was 59.5%.

Unemployment and pessimism

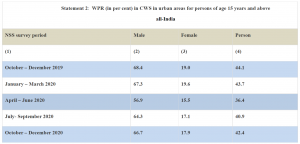

The above phenomenon is further strengthened if we look at the Work Participation Rate. WPR is the percentage of people in the age group of 15 to 59 years who are working. According to the PLFS of 2019-20, India’s WPR was 50.9% in 2019-20, compared with the OECD average of 66.1%. Low average LFPR and WPR for India implies a high rate of unemployment and underemployment among the working-age population. Also, the expectation of getting a job is very bleak among job-seekers. This manifests a very depressed labour market dynamic in India.

Because a large proportion of the working-age population is outside the active labour market, overall aggregate demand also suffers. This is also evident as private consumption expenditure (PFCE) in Q2 FY21-22 (at constant prices) was lower than the corresponding quarter of FY19-20 (₹19.5 lakh crore against ₹20.2 lakh crore), even when the overall GDP was marginally higher (₹35.7 lakh crore against ₹35.6 lakh crore).

READ I Out of coverage: Labour Codes must ensure basic rights to gig and platform workers

The vicious circle

The PFCE’s share in GDP fell to 54.5% from 55.4% in the pre-pandemic quarter of Q1 FY20-21 (https://www.fortuneindia.com/opinion/rising-informal-employment-eclipses-gdp-recovery/106338). Low aggregate demand leads to lower investment and production leading to low demand for labour. Low demand for labour means widespread unemployment. The unemployment situation was worsening even before the pandemic struck.

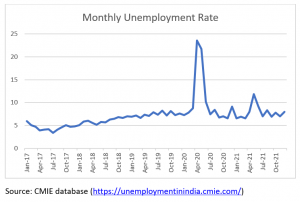

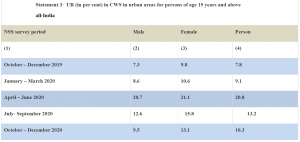

The unemployment rate rose to 7.9% in December 2021. It was 7% in November. A year ago, in December 2020, the unemployment rate was higher at 9.1%. The unemployment rate in India is elevated compared to levels experienced in the recent past. In 2018-19, the unemployment rate was 6.3% per cent and in 2017-18 it was 4.7%. The following graph depicts the unemployment situation in the recent past (pre- and post-pandemic).

The unemployment situation can only improve if aggregate demand increases, but aggregate demand is low because of widespread under-employment and unemployment. The situation was worsening before the pandemic but the pandemic and subsequent lockdown further aggravated the situation. The financial package announced in the middle of 2020 stressed the easy availability of loans and easing of restrictions. However, loan intake failed to register significant growth as the product market remain depressed except for certain sectors.

A judicious policy option would be to take initiatives to raise aggregate demand. Interventions so far mostly hinge on the supply side but the problem remains with the demand side. There is an urgent need to raise aggregate demand by putting more money in hands of the poorer sections of the population. There can be debates on how things can be done. Budget 2022 should find a way to improve the purchasing power of the poor.

Dr Kingshuk Sarkar is an associate professor at the Goa Institute of Management. He has worked as a labour administrator with the government of West Bengal. He earlier served as a faculty member at VV Giri National Labour Institute, Noida and NIRD, Hyderabad. Views expressed are personal.