Rising healthcare spending in India: The issue of fiscal sustainability is an emerging area of policy debate across the world and is not limited to underdeveloped or emerging market economies. This concern has been primarily stirred by mounting population pressure, high debt-gdp ratio, rapid urbanisation, industrialisation and migration, along with fragile capital markets, expanding public sector, and limited physical, natural and financial resources.

It has been often said that the government has failed to meet the budgetary requirements in the social sector, especially in health and education. This claim is being debated by economists and policymakers. Further, the Covid-19 pandemic resulted in a massive surge in demand for health services reflecting shortfall in the health infrastructure as well as health manpower across nations, particularly in developing and least developing countries.

The upcoming trends accentuated the need for huge allocation of funds in the health sector and also led to demands for sustainable budgeting. The term sustainable budgeting is meant to be comprehended as a contract assigning resources for activities, establishing links among various stakeholders, keeping in view the needs of the present and the future generations. Further, sustainable budgeting should aim at digital transformation of services and a rise in remote delivery of services both within and across borders.

READ I Budget 2022 fails to build on govt’s public health initiatives

Given this backdrop, this article attempts to examine the trends in health sector outcomes as well as spending in India, especially during the pandemic period, in relation to sustainable budgeting.

Trends in health sector outcomes

So far as the trends in health sector outcomes in India are concerned, a significant improvement has been seen in vital indicators such as life expectancy, birth rate, death rate, maternal mortality rate, incidence of tuberculosis, and immunisation coverage both in rural and urban areas.

Improvement in life expectancy at 69 years is a noticeable achievement on the health front in India and is also above the world average. The MMR at 130 per 100,000 live births is almost double the 2030 Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) target of 70. Ranked 94 in the Global Hunger Index 2020, India performed satisfactorily among 107 countries. Some other remarkable achievements include improvement in sex ratio from 933 in 2001 to 943 in 2011, decline in birth rate from 25.8 per thousand population in 2001 to 20.4 per thousand population in 2011, decline in death rate from 8.5 per thousand population to 6.4 per thousand population during the same period. In addition, a decline in malarial death rate from 0.10 deaths per lakh population in 2001 to 0.02 deaths per lakh population in 2018 has been reported. Significant improvement in achieving immunisation coverage and achievement of millennium development goals of reversing the incidences of tuberculosis is also noteworthy.

Despite this, certain challenges still persist as India still lags behind many advanced nations with respect to key health indicators. It has been evident that childhood stunting rate of 38% is among the highest in the world. In addition, data on nutritional outcomes also raised a concern as 35.8% of children are underweight and 58.6% are anaemic. (Source: XVFC Vol. 1). Apart from this, wide inter-state disparities persist in health outcomes which are also highlighted in the NITI Aayog report, Healthy States, Progressive India, 2019-20. The overall score in the index of the best-performing state among the larger states was more than two and half times that of the overall score of the least-performing state. Variations in progress among states towards achieving the SDGs persist.

READ I Social security for gig workers of Uber, Ola still a distant dream

Further, surge in out-of-pocket medical expenses is also a major short-coming in the health sector in India since about 60 million people are driven towards poverty due to this. This indicates obstacles in the provision of sound financial risk protection. With the onset of the pandemic, all these vulnerabilities magnified, with long-lasting impacts on learning and nutritional abilities and child and maternal health, thereby, increasing regional inequalities.

Given this, there is widespread concern over sustainable budgeting in the health sector since the Governments at all tiers faced a loss of tax base, and revenue, albeit of different scales.

Trends in government expenditure on health

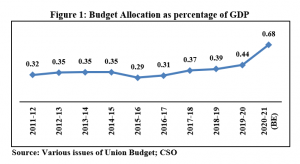

In order to understand the fiscal sustainability of government budget, it is imperative to study the trends in government expenditure in health sector. A glance at fund allocation and expenditure shows that most of the allocation of funds to the health sector is made directly from the ministry of health and family welfare under central sector schemes/ projects and centrally sponsored schemes. A part of the allocation is also made to the department of health and research. The figure below shows budgetary allocations to the health sector as percentage of the GDP which increased from 0.32% during 2011-12 to 0.68% in 2020-21 (BE).

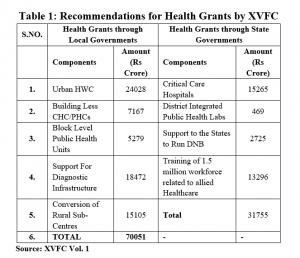

So far as the pattern of expenditure on the health sector is concerned, an enormous rise in government spending has been witnessed during the recent times. The total budgetary expenditure on the health sector by the government (Centre and state governments combined) mounted from Rs 24,355 crore in 2011-12 to Rs 71,269 crore in 2020-21 (BE). In addition to the above, health sector grants are divided into two parts: (i) grants aggregating to Rs 70,051 crore through local governments and (ii) sectoral grants aggregating to Rs 31,755 crore to states (Source: XVFC Vol. 1).

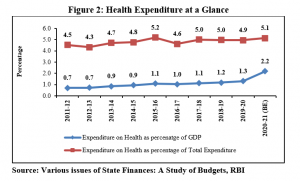

The figure below clearly depicts an upward trend in the healthcare spending of the state governments. It is evident that health expenditure as a percentage of the GDP has substantially mounted to 5.1% in 2020-21 (BE) as against 4.65% in 2011-12. On the other hand, a rise in health expenditure as a percentage of total expenditure from 0.7% in 2011-12 to 2.2% in 2020-21 (BE) has been noticed.

A surge in health expenditure as percentage to GDP and total expenditure reflects the relative importance of health sector in government budgets over the period of time. The above data shows that due consideration has been given to the health sector through various measures to promote the welfare of people.

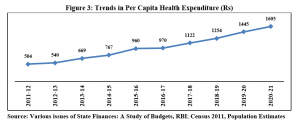

With the objective of providing a comparable level of public services and mitigating regional disparities, infusion of resources by the government has increased per capita health expenditure over a span of 10 years. Per capita health expenditure has increased over the period from Rs 504 to Rs 1,605. Figure 2 clearly shows an upward trend in the per capita health expenditure in India.

It is important to note that the schematic transfers from the Union government to state governments in the form of centrally sponsored schemes (CSS) and central sector schemes amounted to 12.81% of the gross revenue receipts of the Union government during the award period of the FC-XIV (2015-16 to 2019-20). It may also be noted that with an increase in revenue deficit grants by Rs 44,340 crore in the additional supplementary demand for grants announced by the centre in September 2020 on top of the budgeted Rs 30,000 crore on February 1, 2020, it has released the full quantity of revenue deficit grants as recommended by the Fifteenth Finance Commission (FC-XV). Accordingly, the revenue deficit grants in 2020-21 are more than double the average of the previous few years.

This shows that substantial efforts have been made to boost public health spending in the health sector by the government.

Challenges to higher healthcare spending

Certain alarming challenges such as the low level of public healthcare spending, poor health infrastructure in terms of PHCs/CHCs, insufficient focus on core public health functions, shortcomings in the quality of care, weak local governance and lack of accountability in the service delivery model still persist, a fact which has been highlighted in pandemic times. Also, a significant bottleneck in terms of transfers to states has been witnessed through an increase in cash balances of all states from Rs 1.91 lakh crore during 2016 to Rs 1.94 lakh crore by March end in 2019 and Rs 1.88 lakh crore in September 2020, in the form of intermediate treasury bills (ITBs) and auction treasury bills (ATBs) (Source: XVFC Vol. 1). Excessive balances entail costs both in terms of interest payments and lower capital expenditure.

The state governments have demanded substantial funds to invest in health infrastructure through a large number of supplementary memoranda after the onset of the pandemic. Since the responsibility for providing public health service delivery is with them, the need for more financial resources with sustainability issue in the mainstream was seen from the workings of the government during this period of time.

Measures to combat effects of Covid-19 pandemic

In response to the present crisis, an economic stimulus package worth Rs 20 lakh crore (10% of India’s GDP) for Aatmanirbhar Bharat to revive the economy was announced in May 2020. A series of government measures were taken to prioritise the health sector including Covid-19 Emergency Response and Health Systems Preparedness Package of Rs 15,000 crore which included components such as development and operations of dedicated Covid facilities with isolation wards and ICUs, training of health professionals, augmenting testing capacity, procurement of personal protective equipment (PPEs), N-95 masks, ventilators, testing kits and drugs, conversion of railway coaches as Covid care centres, strengthening surveillance units and untied funds to the districts for emergency response (Source: XVFC Vol. 1).

Further, the fifth tranche of Aatmanirbhar Bharat package proposed to increase public health expenditure by investing in grassroot health institutions and ramping up health and wellness centres (HWCs) in rural and urban areas, setting up critical care hospital blocks in all districts, and strengthening and integrating by integrated public health laboratories in all districts, blocks and public health units (Source: XVFC Vol. 1).

In addition to the above, state governments have also been proactive in undertaking policy measures to contain the impact of the pandemic alongside the Union government. Measures such as financial support in the form of insurance cover for doctors and the nurses, purchase of medical equipment and tools, hospital arrangements with a sufficient number of beds for Covid-19 patients, providing food free of cost, cash for those who are not availing of any government schemes, cash for registered construction workers, remitting a fixed sum for those trapped abroad in other states, and advance salary and pension payments were adopted on priority basis. An example has been laid down by Kerala with the involvement of local self-governments in the fight against the pandemic through infusion of resources and transformation of public services.

The above discussion shows that a number of discrete steps have been taken up the government to boost the health sector and promote health service delivery in India over the period of time through various means despite persistent adversities during the pandemic.

Conclusion and policy recommendations

It can be concluded that in order to achieve the desirable amount of sustainable budgeting, there is a need for considerable infusion of resources by the government, which will not only help achieve the target of health outcomes but also help in realising the objective of sustainable budgeting.

In this context, a number of policy recommendations have been put forth by the Fifteenth Finance Commission to serve as a catalyst to combat the adversities of the pandemic and health sector vulnerabilities ranging from better public health service delivery to enhancement in health sector grants. The details of these have been summarised below:

The Fifteenth Finance Commission has also given certain policy recommendations which are indirectly related to sustainable budgeting. These are:

- Increase in health sector spending by the states up to 8% by 2022 as against the earlier recommendation of 6%.

- Increase in primary health expenditure to two-thirds of the total health expenditure by 2022.

- Increase in public health expenditure of the Union and state governments together to 2.5% of the GDP by 2022.

- Flexible CSS to allow states to adapt and innovate.

- Shift of focus of inter-governmental fiscal health financing from inputs to outcomes.

The policy measures also have a framework designed to contain the adversities in the health sector and ensure sustainable budgeting. In addition, a multi-sectoral integrated approach is required to improve the efficiency mechanism at all tiers of the government, combined with clear demarcations of the health indicators and outcomes, and attain public healthcare spending of about 6% of the GDP in alignment with fiscal sustainability.

(Dr Shelly Dahiya is a young professional at NITI Aayog.)

References:

Jena, Pratap Ranjan & Sikdar, Satadru (2019). Budget Credibility in India: Assessment through PEFA framework. NIPFP Working Paper Series. Working Paper No. 283.New Delhi.

Fifteenth Finance Commission (2020). Finance Commission in Covid Times Report for 2021-26. Vol 1. New Delhi.

RBI. State Finances: A Study of Budgets. Various Issues.

Union Budget. Various Issues.

Central Statistical Organisation. GSDP. New Delhi.

Census 2011. Population Tables.

Dr Badri Narayanan Gopalakrishnan is Fellow, NITI Aayog. Views expressed are personal.