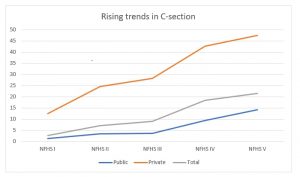

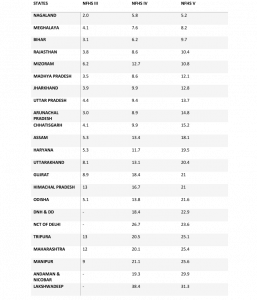

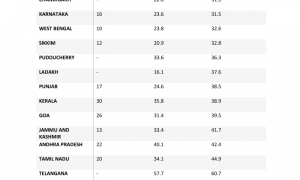

The robustness of a country’s healthcare system is gauged by its ability to manage maternal mortality which indubitably influences infant outcomes. An alarming increase in C-section numbers in India is a major cause for concern. The national average of C-sections has touched a new high at 26%, crossing the 10-15% range recommended by the World Health Organisation for better maternal and neonatal outcomes. Major contributors to the higher rates are private facilities. The increase is most noticeable in the southern states, which are economically prosperous.

There are a number of reasons for the spurt in C-section numbers. These range from maternal factors (age, education, experience) to provider-related factors (convenience, fear of litigation), but monetary benefits are the most important among them. The concerns over the surge are due to its adverse effects on neonatal and maternal health outcomes. C-sections are meant to replace vaginal delivery only during emergencies or complications and are associated with decreased perinatal morbidity. Thus, WHO has recommended 10–15% as the optimal range for C-sections to yield optimal health outcomes.

READ I Budget 2022 fails to build on govt’s public health initiatives

Denying benefits of normal delivery

As they say, too much of anything is good for nothing. The rising C-section numbers is adversely affecting the health outcomes of mothers and children. As babies delivered through C-sections are not exposed of the vaginal bacterial flora, the immune system of the child can be affected, leaving them susceptible to autoimmune diseases. Various outcomes pertaining to the development of cognitive and motor skills in the first year of life were studied in babies delivered through normal methods. Neonatal outcomes with an increased risk of neonates facing respiratory issues were also associated with C-sections.

This is because babies acclimatise to breathing during parturition in the procedure of vaginal delivery, which is unlikely to occur otherwise. Due to the type of anaesthetic used, C-sections also pose a hindrance to the early breastfeeding of infants. In the case of C-sections used in true emergencies, regional anaesthesia is given so the mother is aware and awake to bond with and feed the infant, which is not feasible with C-sections. It equally affects maternal health. The postpartum quality of life is also deemed to be affected by the C-section. This adds to the complications a woman is subjected to when opting for a C-section when it is not medically recommended.

Reasons behind rising C-section rate

The factors contributing to the rise in C-section numbers are majorly provider-related. One major provider-related factor is profiteering, but the question remains if the demand is always supplier-induced. Inadequate resources, management and guidelines, fear of litigation and violence, patient choice and convenience, time and financial constraints, and the lack of effective technical assistance during surgery also play a role in the rise in the rate.

The consumer-provider relationship including the maternal demand also adds to it. This demand is influenced by past experiences, fear of pain, level of education, increased autonomy, and better socio-economic status. This explains the higher C-section numbers in the southern and economically well-off states.

The increase in adversities and morbidities with the rising number of C-sections is putting maternal and child health in jeopardy and putting future public health outcomes at stake. This is due to the potential course of life cycle that these adversities set, putting the health of the population at risk. The government of India set up a body to regulate C-section numbers in every region when MP KC Ramamurthy raised this question in Parliament. It is high time that the government took the matter into its own hands and implemented stringent guidelines to curb the rampant use of C-sections which exposes mothers and children to the adversities of ill-advised C-sections.

Maternal-related factors can be curbed by conducting counselling sessions during every antenatal visit to help prepare the mother to undergo vaginal childbirth, provided no potential complications are associated with labour. IEC of women during antenatal care visits pertaining to information about the future risk that is associated with voluntarily opting for C-section or painless delivery methods can enable them to make informed choices. Accessibility and logistical failure are major impediments to a complication-free delivery, particularly in rural areas where the facility is located in remote locations.

Failure to access skilled professionals and hospitals increases the chances of complications, thus indicating a C-section. Maintenance of records and regular follow-ups of mothers, especially those with closer due dates, training ASHAs, and developing midwifery skills can further alleviate ill effects. Though these functions are covered under various programmes under NRHM, emphasis should be laid on implementing outreach strategies to extend reach and coverage. Provider-related factors are crucial to bringing down the rates.

To limit the monetary benefits incurred by patients, capping the rates of both the procedure and provisioning uniform remuneration for both the methods of delivery must be considered. This will curb the profit-making motives of the care providers, preventing looting of patients. As the government has constituted a body to regulate rising C-section numbers, it must also work on formulating basic common guidelines that ensure uniformity among practitioners, prevent chaos, and ensure active management of labour.

This must be in addition to strengthening the skills of the workforce under obstetricians, nurses, and midwives to implement shared practice rather than solo practice wherein the doctor has the sole pressure and accountability for handling the dynamics of labour amid unskilled assistants. This can be curbed by increasing the doctor-patient ratio.

Collaborative efforts and stringent regulation of C-sections are the ways to calm the chaos. Healthcare has become a business and is treated as a commodity rather than a right. So, this market for healthcare is influenced by consumers too. If the population is well informed of the adverse effects, the situation will soon shift from supplier-induced demand to consumer-driven demand. The C-sections have financial repercussions, pushing the uninformed and destitute into poverty. Thus, considering the wrath it brings, regulating C-section numbers and maintaining them within the range recommended by WHO to yield improved maternal and child health outcomes is the need of the hour.

(Sharyu Mhamane & Dr Vanisree Ramanathan are from School of Public Health, MIT-World Peace University, Pune. Views expressed are personal.)