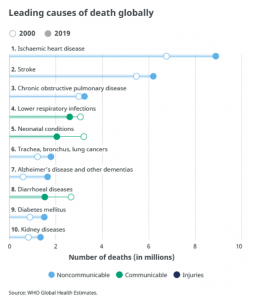

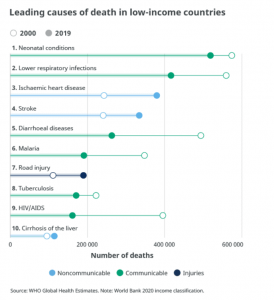

Noncommunicable diseases kill 41 million people each year, accounting for 71% of all deaths globally. Each year, more than 15 million people between ages 30 and 69 years die of NCDs. At least 85% of these premature deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries. Around 77% of all NCD deaths are in low- and middle-income countries.

Cardiovascular diseases account for 17.9 million deaths annually, cancers 9.3 million, respiratory diseases 4.1 million, and diabetes 1.5 million. These four groups of diseases account for more than 80% of all premature NCD deaths. Detection, screening, treatment, and palliative care are critical components of the response to NCDs (WHO 2021).

WHO’s analysis of the four NCD groups, risk factors and responses does not present the whole story. Because of the substantial costs, it is difficult to treat the NCD epidemic (Buse et al., 2017). Instead, more effective prevention strategies are needed to reduce the risk factors associated with these diseases.

READ I Universal health coverage makes sense – both in ethics and economics

Public health action to prevent NCDs has primarily focused on metabolic (e.g., hypertension, hyperlipidaemia) and modifiable behavioural risk factors (tobacco use, harmful alcohol use, unhealthy diets and physical inactivity). As a result, as Horton describes, progress has been inadequate and disappointingly slow. An advocacy strategy based on four groups and their risk factors seems increasingly out of touch with the wider determinants of health (Horton, 2017).

A transdisciplinary approach is enabling public health students to unpack the complexity of determinants of health. There is a growing body of knowledge on how corporations’ commercial decisions and collusion with or through the lapse of state action determine the population’s health.

It appears that the current public health models do not adequately frame public health problems and solutions in ways that illuminate the role that large corporations play in shaping the broader environment and individual behaviours and population health outcomes (Maani et al., 2020).

There are critical public health studies and data is emerging on the impact of the corporate sector on unhealthy commodities, industrial epidemics, profit-driven diseases, corporate practices harmful to health and the commercial sector as a structural driver of inequalities in health and well-being.

READ I Universal health insurance a distant dream without healthcare reforms

Industrial epidemic and public health

The concept of an industrial epidemic applies public health concepts and shifts the policy focus from the ‘agent’ (i.e., alcohol) or the ‘host’ (e.g., the problem drinker) to the ‘disease vector’ (i.e., the alcohol industry and its associates), which in many ways is responsible for the exposure of vulnerable populations to the risks of alcohol.

The concept of industrial epidemics applies to tobacco and nicotine addiction, food additives and obesity, automobile accidents, lead poisoning, diseases caused by exposure to asbestos, polyvinyl chloride and other chlorinated hydrocarbon plastics, beryllium, and diesel engine fumes (Jahiel RI, 2007).

According to Mialon, the term corporation refer to individuals and organisations involved in the production, distribution and marketing of commodities: manufacturers, wholesalers, retailers, distributors, service providers, and producers of raw material, as well as organisations acting on their behalf, such as trade associations, public relations firms, philanthropic organisations, and research institutions. (Mialon, 2020 )

Kickbusch and colleagues defined Commercial determinants of health as strategies and approaches used by the private sector to promote products and choices that are detrimental to health. (Ilona Kickbusch, 2016)

WHO further defined commercial determinants of health are corporate actors’ conditions, actions, and omissions that affect health. They may operate within or outside the regulatory framework of the government. Commercial determinants arise in providing goods or services for payment and include commercial activities and the environment where commerce occurs. They can have beneficial or detrimental impacts on health. (WHO, 2021)

Mialon further identified the commercial determinants of health, covering three areas. First, they relate to unhealthy commodities that are contributing to ill-health. Secondly, they include business, market and political practices harmful to health and used to sell these commodities and secure a favourable policy environment. Finally, they include the global drivers of ill-health, such as market-driven economies and, that have facilitated the use of such harmful practices. (Mialon, 2020 )

Many corporations also make positive contributions through their primary activities, such as discovering and developing medicines, promoting affordable generic medicines, philanthropic activities, improving the worker’s health and health-related public-private partnerships.

READ I Sustainable development: Climate change, Covid force changes in economic priorities

Use of marketing, lobbying

Corporate influence in public health is exerted through marketing, lobbying, corporate social responsibility strategies, and the management of supply chains. In some settings, the state role is merged with the role of corporates and influence public health through state’s failure in protecting the best – health interest of the population. While some analysts focus on individual ‘lifestyles’ as the determinants of diseases, marketing—an essential commercial determinant— which shapes the lifestyles is very rarely mentioned in their analysis.

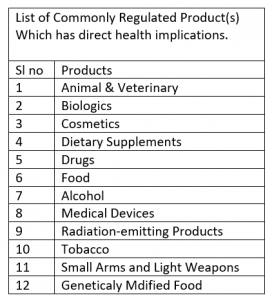

The food and beverage industry, pharmaceutical industry, private health care industry, health insurance industry, transport industry, sports industry, the tobacco industry, media, including social media, small arms and light weapons industry can determine and influence a great deal of health and well-being.

There are specific pathways through with corporates determine the health and wellbeing of the population. Marketing is used to enhance the desirability and acceptability of unhealthy commodities. State also could be a marketing party bi-directionally, as a direct corporate agent and failure to regulate unhealthy marketing strategies. Corporates are actively involved in lobbying, which can impede policy barriers such as plain packaging of tobacco products, labelling of the contents in food packets, minimum drinking age and promotion of alcohol.

Corporate social responsibility strategies are increasingly used to deflect attention and polish corporations’ public health reputations. Many corporates have extensive supply chains, often better than the public health supply chains, which amplify company influence around the globe. These channels boost corporate reach and magnify the health impact of commercial enterprise. As the breadth and depth of corporate influence expand, more people are reached with ever more consumption choices with catastrophic health consequences.

The state has a critical role in consumer protection activities, focusing on regulatory and compliance actions. In addition, the State may address the broader economic factors impacting health and health equity through regulations on trade and health and health and development. It also could promote fiscal instruments, including taxation policies, to invest in fundamental health research and improve health outcomes.

State guidance on food fortification is an example of state action on commercial determinants of health. Food fortification adds vitamins and minerals to commonly consumed foods during processing to increase their nutritional value. It is a proven, safe and cost-effective strategy for improving diets and preventing and controlling micronutrient deficiencies.

The policies should reduce exposure to toxic elements in foods commonly eaten by babies and young children to the lowest possible levels. State mediated food safety measures ensure reduction and control of the longstanding problem of foodborne illness. Despite campaigns encouraging healthy eating, children living in deprived areas are now more than twice as likely to have obesity than those living in the least deprived areas.

While various factors could be responsible, such as poorer areas usually having a more significant number of fast-food outlets than their counterparts, the root of some of the disparities can start as early as birth. Many states are introducing sugar taxes and enforcing the ban on junk food advertising. They are actions in the right direction.

Equally important, though perhaps less understood, is the role of state activities or its absence of the generic drug review process, which support public health by ensuring that essential medical products are available and accessible to people who need them. For example, the Covid19 pandemic resulted in severe shortages of critical drugs, devices and biologics.

Making these products’ supply chains robust, reliable and redundant is a state responsibility. In addition, state has a critical role in the safety and availability of the blood supply, ensuring the safety, effectiveness, and availability of vaccines, overall monitoring the safety of human and animal food and ensuring the quality and safety of medical products on the market.

Many states are also gradually catching up with commercial entities’ genetically modified organisms. As a result, states are introducing national schemes for regulating genetically modified organisms to protect the health and safety of the populations. The States needs to identify risks posed by or due to gene technology and manage those risks by regulating dealings with genetically modified organisms.

Protecting the public from medical product fraud is a critical role of state. Fake online pharmacies and miracle cures are two common forms of medical fraud. Both involve the sale of medical products which may be dangerous or ineffective.

The state has to constantly modernise the processes and digital systems and keep pace with evolving science and technology. In addition, the state needs to promote the development of new and innovative products—drugs, biologics, medical devices, and medical foods—that demonstrate significant promise for the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of rare diseases or conditions.

The ability of the state apparatus to adapt quickly and identify solutions in real-time to ensure new health products are monitored and regulated. Rare diseases are difficult to study and offer fewer economic incentives for product development. The State need to develop programs intended to help advance treatments for these conditions.

This includes emergency responses to many different types of challenges within the broad spectrum of regulated health products, including foodborne illnesses, product tampering issues, human-made and natural disasters, and emergencies affecting public health, staff, systems, and facilities.

As Maanie et al. (2020) observed that public health urgently requires rapid evolution of existing social and structural determinants of health and thinking to extend the core concepts to more fully consider the commercial determinants of health. It also requires health policymakers and public health practitioners to hold powerful commercial actors, state inaction or collusion to account for their actions.

In the absence of this, current public health conceptual frameworks may risk framing public health problems and solutions in ways that inadvertently obscure the role that the private sector, particularly large transnational companies, plays in shaping the broader environment, individual behaviours, and population health outcomes.

References

Buse, Kent, Sonja Tanaka, and Sarah Hawkes. (2017). “Healthy People and Healthy Profits? Elaborating a Conceptual Framework for Governing the Commercial Determinants of Noncommunicable Diseases and Identifying Options for Reducing Risk Exposure. Global Health. 2017; 13: 34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-017-0255-3.

Horton, R. (2017). Comment: NCDs – why are we failing? Lancet, 390: 346. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(17)31919-0/fulltext.

Jahiel RI, Babor TF (2007). Industrial epidemics, public health advocacy and the alcohol industry: lessons from other fields. Addiction. 2007 Sep;102(9):1335-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01900.x. PMID: 17697267

Nason Maani, Jeff Collin, Sharon Friel, Anna B Gilmore, Jim McCambridge, Lindsay Robertson, Mark P Petticrew (2020), Bringing the commercial determinants of health out of the shadows: a review of how the commercial determinants are represented in conceptual frameworks, European Journal of Public Health, Volume 30, Issue 4, August 2020, Pages 660–664, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckz197

WHO (2021) Commercial Determinants of Health. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/commercial-determinants-of-health

Ilona Kickbusch, Luke Allen, Christian Franz (2016). The commercial determinants of health. The Lancet Global Health. Vol 4, Issue 12, E895-E896, December 01, 2016. December, 2016DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30217-0

Dr Joe Thomas is Global Public Health Chair at Sustainable Policy Solutions Foundation, a policy think tank based in New Delhi. He is also Professor of Public Health at Institute of Health and Management, Victoria, Australia. Opinions expressed in this article are personal.