India’s internal migration: With the possibility of migrant workers from North India leaving Tamil Nadu looming large, manufacturers in the southern state are in a panic mode as reverse migration is bound to have a huge economic cost. The workers are expected to leave the state after videos of Hindi-speaking men being assaulted surfaced over the internet. However, the state government has been quick to reject them as fake. Nonetheless, the panic in the hearts of migrant workers is real.

That Tamil Nadu will bear huge economic cost from the exodus can be asserted from the fact that a large-scale reverse migration of workers to their home states during the Covid-19 lockdown three years ago had seriously disrupted economic activity. Tamil Nadu has nearly 10 lakh migrant workers. According to the latest available data with the government, the number of internal migrants in India stood at 45.36 crore. However, the number is not reliable since it is a decade old data from the 2011 census. Going by the available numbers, every third person in the country is a migrant. This number is inclusive of both inter-state migrants and migrants within each state.

READ | Public procurement: Periodic review of preferential treatment can ensure cost effectiveness

It goes without saying that the biggest cities in India see the highest influx of migrants within the country with Gurugram, Delhi, and Mumbai topping the list. These cities are economic hubs, making them highly attractive for migrant workers. Other cities with high numbers of migrants are Indore and Bhopal (Madhya Pradesh); Bengaluru (Karnataka); and Thiruvallur, Chennai, Kancheepuram, Erode, and Coimbatore (Tamil Nadu), according to migration data in the Economic Survey for 2016-17.

What causes internal migration

India’s internal migration is driven by a combination of economic, social, and political factors. The most important reason for workers leaving their homes is better employment opportunities which may be lacking at their own places. Many people migrate from rural to urban areas in search of better job prospects and higher wages. Urban areas offer a range of employment opportunities, including manufacturing, services, and construction. Poverty and lack of access to basic amenities like water, sanitation, and healthcare is also a chief driver of internal migration.

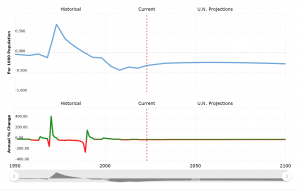

India net migration rate 1950-2023

India is a divided nation in terms of caste and creed and such discrimination can also lead to migration. Political instability and conflict can also drive people to migrate, particularly in regions that are affected by ethnic or religious tensions.

India’s migration hotspots

There are several regions in the country which continue to report high outflow of workers. This includes Muzaffarnagar, Bijnor, Moradabad, Rampur, Kaushambi, Faizabad, and 33 other districts of Uttar Pradesh. Uttarakhand’s cities including Uttarkashi, Chamoli, RudraPrayag, Tehri Garhwal, Pauri Garhwal, Pithoragarh, Bageshwar, Almora, and Champawat also report heavy outflow of migrants. Among other states with high numbers of migration are Rajasthan, Bihar, and Jharkhand.

In fact, 17 districts combined accounted for a quarter of India’s total male out-migration, according to the report of the Working Group on Migration, 2017. Ten of these districts are in UP, six in Bihar, and one in Odisha. Relatively less developed states such as Bihar and Uttar Pradesh have high net out-migration while relatively developed states such as Goa, Delhi, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Karnataka take positive CMM (Cohort-based Migration Metric) values reflecting net immigration.

However, despite leaving their homeland, the workers may still be subjected to discrimination as is alleged in the case of Tamil Nadu. There are other challenges to migrant workers especially in terms of infrastructure which may be lacking in urban areas at times. This lack of sufficient infrastructure, including housing, water, sanitation, and healthcare, can become even more challenging for outstation workers.

Further, workers who come from other states may often find themselves at mercy of their employers, brokers, or landlords, who may take advantage of their lack of local knowledge. According to reports on the health of migrant workers, it is also found at times that they feel socially isolated and disconnected from their families and communities.

READ | Clipping the wings: Is India sabotaging its telecom sector

Among other challenges faced by migrant workers, those who are seasonal workers are often employed in low-paying, hazardous and informal market jobs, according to the World Economic Forum. Key sectors in urban destinations in which these workers find jobs are construction, hotel, textile, manufacturing, transportation, services, domestic work etc. With poor access to health services, they often have poor occupational health. A large number of migrants find work as unskilled labourers since they enter the job market at a very early age.

Migrants are often deemed the responsibility of their government, but the internally displaced can neither be refugees, nor migrants from another country. Yet, many of the needs and circumstances for the internally displaced can be very similar to those of refugees. Theirs is actually a paradox of being both a citizen of a country and a migrant within it at the same time. While the Indian government is bound by commitments to safeguard the human rights of citizens and non-citizens alike, it is not doing so.

To help migrant workers, the existing legal machinery must be made stronger to protect their interests. At present, the legislature is not sensitive to the nature of legal disputes in the unorganised sector, according to the WEF. Many informal sector disputes never make their way to labour courts or keep languishing in courts for lack of proof.