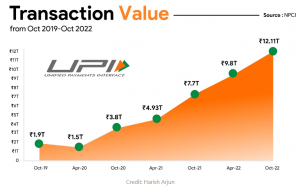

Economists at the State Bank of India made a startling discovery during Diwali. In the festival week, cash in circulation in the country fell for the first time in 20 years. The season generally sees an increase in cash circulation as shopping hits its annual peak. It is not that markets were quiet and consumers did not buy stuff this year. It’s just that they were paying for their purchases electronically.

“The Indian economy is going through a structural transformation,” SBI’s Ecowrap report said. “The small retail payments done through UPI/e-wallets holds around 11%-12% in the payment industry.” Digital transfers now form over 80% of all transactions, up from 11% in 2016.

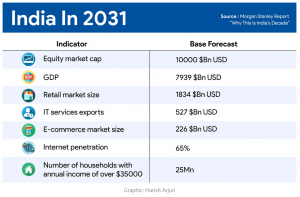

This structural shift is set to power India’s economy in the next few years as its heavy public investment in digital infrastructure is about to pay off. Digitisation of the economy, along with energy transmission and offshoring, supported by a government veering away from redistribution to profits will drive India’s growth in the next decade, according to Morgan Stanley. “These will make it the world’s third-largest economy and stock market before the end of the decade,” the US financial services giant forecast in a report titled Why This Is India’s Decade. Underpinning it will be the global trends of demographics, digitisation, decarbonisation, and deglobalisation.

READ I Slow GDP growth no big concern amid global recession fears

Flashback: BRICs and Indian economy

Morgan Stanley’s prediction comes 20 years after another US superbank, Goldman Sachs, slotted India with a fast-growing bunch of emerging economies that would shift the global economic power away from the US and Europe. Those were the days immediately after the spectre of international terrorism visited the US with all its force. Aeroplanes not only brought the twin WTC towers crashing down on 9/11, but also devastated markets all over the world, and as the US prepared for vengeance, sowed doubts about growth prospects.

Weeks later, in November 2001, Goldman Sachs’ global head of economic research, Jim O’Neill, proposed the reordering of international economic policymaking, which was dominated by the Group of Seven countries, or G7, to accommodate emerging economies. “It is time for better global economic BRICs,” O’Neill wrote in his eponymously titled paper. The relative weight of Brazil, Russia, India and China (BRICs) in the global economy was set to rise from 8% to 14.2% in 10 years. They were already 23.3% of global GDP measured by purchasing power parity, he wrote.

It was an unmistakable pointer to global investors that it was time they headed to new markets. Emerging markets, especially those in Asia, were poised for the next phase of value creation. The paper unambiguously recognised the rising clout of China even if it was more ambivalent about the other three, especially India. But it recognised the collective potential of the group. A follow-up paper two years later forecast that BRICs would be collectively bigger than the G6—the US, Japan, the UK, France, Germany and Italy—in less than 40 years. It said China would overtake the US in 2041 and India would pass Japan’s economy in 2032.

READ I Digital Rupee explained: Retail CBDC offers savings for RBI, anonymity for customers

The formulation so captured policymakers’ imagination that leaders of BRICS (including South Africa) nations instituted an annual summit and even established a bank.

True to the forecast, China is now the second-largest economy and India recently surpassed the UK as the fifth largest. Among the four, India, it said, would sustain the highest average growth rate (over 5%) for a long period of time. Between 2001 and 2021, India grew at an average annual growth rate of 6.08%, as per World Bank data.

The key, Goldman Sachs suggested, was to focus on skilling a young workforce to reap the demographic dividend and keeping India open to trade and foreign investment. But like many countries, except China, India seemed to founder after the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-09. It was because the country turned to welfare and redistribution, says Morgan Stanley.

READ I India’s economy from Nehru to Modi – a conversation with Pulapre Balakrishnan

Profits over redistribution

The conditions now are similar to that in the early 2000s. Asia was coming out of a currency crisis that gripped the region in the late 1990s. India cleaned up its balance sheet and put policies in place that pushed private investment, leading to the high growth phase of 2003-2007.

The foundation of the country’s growth in the next few years would be the government, which has, beginning 2019, shifted focus from redistribution to profits. India’s growth slowed down because the share of profits in GDP peaked in 2007, a year after the rural job guarantee scheme MGNREGA (short for Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act) was introduced. Structurally, raising wages does not work for India. “For India, a policy to boost profits—and then investments that create jobs and wages—appears to be a more reliable approach to generating higher real growth,” the report said.

The policy choice between redistribution and fast growth was also the centrepiece of an intense debate between two stalwart economists, Nobel laureate Amartya Sen and Columbia University professor Jagdish Bhagwati, in 2013. It was also pitted as a contest between the Kerala and Gujarat models of development, Sen rooting for the former and Bhagwati backing the latter. Although it remained inconclusive then, Bhagwati seems to have eventually won over Indian policymakers.

Economists believe that a country’s growth depends on what is known as total factor productivity (TFP). It is a measure of output against the input of capital and labour. If output rises at a rate faster than the rate of incremental capital employed and labour deployed, it means productivity is increasing. Technological improvements and innovations often help the same number of workers produce more and cut costs raising productivity. It is known as Solow residual and is based on Nobel Prize-winning economist Robert Solow’s work. In short, rising TFP helps fuel growth.

Until now, China’s TFP at 4.1% was double that of India. But that is set to change as investments and employment rise. India will begin averaging a TFP of 3.4%, while China’s will drop to 1.2%, the report said.

India has invested heavily in publicly funded and owned digital infrastructure. Morgan Stanley says Aadhaar, India Stack, the Open Network for Digital Commerce (ONDC) and the Open Credit Enablement Network (OCEN) would be key drivers of productivity and economic activity. The country’s transition to green energy will be yet another factor. Combined, these will bring supply chains to India. But crucial to these structural components of the new Indian economy is the base of government policy.

Infosys founder and Aadhaar architect Nandan Nilekani has said that India was moving from a prepaid to a postpaid economy as digitisation will make it easier for lenders and sellers to assess the paying capacity of borrowers and buyers. Nilekani said that while the internet private sector, comprising companies such as Google and Facebook, was built on advertising revenue, India will build its companies based on transactions. It will drive the consumption cycle, he said.

Lower corporate tax rates, government support such as the Productivity-Linked Incentive scheme, and changes to legal frameworks will help improve private-sector profits and attract capital. Indian economy will be among the top three in the world that will add $500 billion annually to its output to become a nearly $8 trillion economy by 2031, Morgan Stanley forecasts. Acche din, anyone?

(This article was first published in The Intersection by The Signal.)