The recent G20 summit reignited global conversation on climate action, with India leading the way for the Global South. However, translating climate action targets into outcomes depends on securing adequate funds. While adaptation discourse is often overshadowed by the growing focus on net-zero targets and mitigation strategies, financing for this domain has become a significant concern. Renewable energy and green mobility have historically attracted most global funds, with little attention paid to the adaptation finance gap. There is an urgent need to address this issue with policy focus.

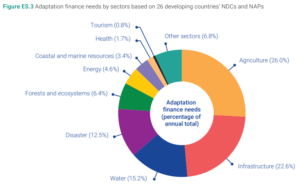

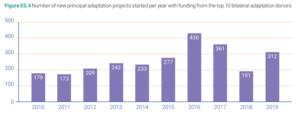

In 2020, the estimated cost of adaptation stood at $349 billion, yet only $5 billion was invested. One reason is the limited and inconsistent availability of international and multilateral adaptation funds. Additionally, the failure of developed nations to deliver promised bilateral finance and the Green Climate Fund’s (GCF) cap of $10 million per country further restricts India’s access to necessary funds. The bureaucratic complexities associated with the GCF also pose significant hurdles, impeding timely and effective fund allocation. As a result, vulnerable sectors like agriculture and fishing, crucial for India’s economy and food security, struggle to build resilience against climate shocks.

READ I Modi 3.0: Bold reforms needed to unleash demographic dividend

India faces adaptation finance gap

India’s adaptation financing efforts reveal a heavy reliance on domestic sources, which accounted for 94% of total adaptation finance in 2019-2020, while international funding constituted a mere 6%. Although the Union government spending on adaptation as a percentage of the GDP has shown steady growth from 1.45% in 2000-01 to 5.60% in 2021-22, this increase is insufficient to bridge the substantial finance gap. Moreover, state governments’ low contribution to adaptation finance, coupled with their reliance on Union budget, fosters a competitive rather than collaborative approach, further complicating the allocation of necessary resources.

Mobilising private investment for climate adaptation remains difficult. Unlike mitigation projects which offer clear profit-generation opportunities, adaptation projects are perceived as less lucrative. Currently, less than 0.1% of adaptation finance comes from the private sector, compared with 53% in the mitigation sector. While some private players are involved in providing agri-services like weather and market information, the overall market for private adaptation finance is nascent and fragmented.

A slew of institutional and governance issues further complicate adaptation finance in India. The lack of a clear definition and standardised tracking of adaptation finance leads to overlapping projects and ambiguities, making it difficult to monitor and evaluate progress. Moreover, weak governance structures and a lack of inter-ministerial coordination delay fund disbursement and approval. The silo culture within ministries, where climate change issues are narrowly viewed as the responsibility of the ministry of environment, forest and climate change, leads to mismatched leadership and insufficient engagement from the ministry of finance which is crucial for budget allocation.

Strategic interventions needed

The decision of global financing for an adaptation project goes beyond the vulnerability of the country, and relies more on the suitability of the institutional arrangements for absorbing the funds. Therefore, India needs better coordination and collaborative efforts from different departments and active leadership from the ministry of finance in adaptation financing. An autonomous government body, similar to the National Adaptation Fund for Climate Change, can be set up to review and monitor adaptation governance in India. This body can also be responsible for formally tracking finances and maintaining a database. The scope of work can be extended to preparing and managing an empirical database for informed adaptation financing to mobilise private capital.

Union budget alone cannot narrow the adaptation finance gap, implying an immediate need for private investment. There should be efforts and suitable policies from the government to channel private funds. The private sector’s primary concern is the risk associated with any adaptation project. Public finance should intervene in the primary risk area to incentivise private investment.

Consequential risk, the most challenging part, can be addressed by sovereign or public resources, such as insurance and weather derivatives. Raising awareness about business opportunities in the adaptation domain and providing better access to technical support for businesses to bear the risk and grow are essential to foster private capital in adaptation. Clear guidelines for private financing in adaptation, ensuring community benefits, are needed to prevent the misallocation of funds.

Along with private capital, the government needs to recognise the potential role of corporate social responsibility (CSR) funds in adaptation financing. Currently, only 5-8% of CSR funds are dedicated to environmental sustainability, which requires more attention to improve the share.

Developing countries have become a new marketplace for philanthropic funds, leading to a new form of dependency on the developed world. Enabling local governments and engaging civil society organisations through capacity-building programmes and training is essential for grassroots stakeholders to manage the complexities of adaptation finance, make global finance accessible, and facilitate a fair power balance.

India’s ambitious adaptation goals and its current financing deficit reveal a dissonance that demands urgent attention. To effectively bridge the adaptation finance gap, India needs a multifaceted approach encompassing better institutional coordination, strategic use of public and private funds, and robust community engagement.

The G20 summit’s emphasis on public-private partnerships is a step in the right direction, but without concrete measures to ensure equitable access and grassroots involvement, India’s adaptation efforts may fall short. Climate adaptation is not just a technical challenge but a moral imperative to protect the most vulnerable communities. As India navigates its climate journey, strong political will and strategic interventions will be crucial in transforming its adaptation finance landscape and securing a resilient future for all.

(The author is a research associate at CUTS international, an India-based global policy think tank and advocacy group.)