The dollar has held a dominant position in the global economy in the last 80 years as a widely accepted medium of exchange and store of value. Dedollarisation refers to the process of reducing reliance on the dollar by countries for transactions, unit of account, and reserve currency purposes. Dedollarisation aims at making the dollar less indispensable in international trade, gradually substituting it with other currencies, gold, or alternative arrangements.

The dollar gained global prominence by displacing the pound sterling as the international reserve currency in the 1920s after the First World War and the heavy inflow of wartime gold. The Bretton Woods Agreement of 1944 further strengthened the position of the dollar by fixing the value of gold at $35 per ounce. Over time, the scarcity of gold limited its use, leading to the emergence of a few reserve currencies including the dollar and the pound. The Great Depression and the Second World War eroded the strength of the British economy, forcing it to abandon the gold standard, resulting in it losing its power in global transactions.

READ I Shadow Banks: Navigating the complex landscape of NBFCs

Since 1944, the global economy was dollarised to address economic instability, high inflation, and the desire to protect assets from fluctuations in currency value. Dollarised economies benefited from increased confidence among global investors, lower interest rate spreads on international borrowing, reduced fiscal costs, and enhanced investment and growth. The suitability of dollarisation as an exchange rate regime for developing countries depends on their unique characteristics.

Maintaining the fixed exchange rate of $35 per ounce of gold within a narrow range became increasingly challenging for the US, especially due to growing demand for international liquidity. The US resorted to printing more currency to address the shortage of dollars which led to the collapse of the Bretton Woods system. In 1971, the Smithsonian Agreement allowed for a flexible exchange rate regime, with occasional interventions termed as managed floating exchange rates.

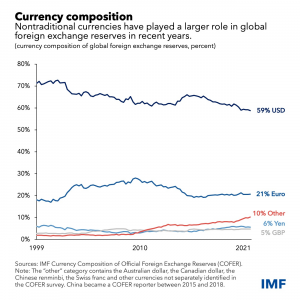

The dollar continued to serve as a strong reserve currency in international trade and investment. Reserve currencies are held by central banks as foreign exchange reserves, facilitating international payments and acting as a buffer for contingencies. The dominance of the dollar allowed the US to impose unilateral sanctions on actions between other countries. The dollar’s share of global reserves was around 72.93% in 1965 and reached its peak at nearly 85% in 1970 and 1975. By 2022, its share decreased to 58.3%, while other currencies like the euro, Japanese yen, pound sterling, Chinese renminbi, Canadian dollar, and Australian dollar gained some ground.

Dedollarisation has gained momentum with countries seeking to reduce their dependence on the dollar. Trade and transactions are increasingly conducted in local currencies, gold, and other resources. Central banks started adding more gold to their reserves since 1987 and the process gained momentum after the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine war. The war led to the freezing of Russian foreign currency reserves and the expulsion of Russian banks from the SWIFT international payment system. India has allowed invoicing of exports and imports in Indian rupee, setting up a rupee trade settlement mechanism to attract other countries.

Why countries eye dedollarisation

Countries have various motivations for dedollarisation. One reason is to minimise their vulnerability to economic and political risks associated with the US. For instance, if the US economy enters a recession, the value of the dollar could decline, negatively affecting countries holding substantial amounts of US currency.

Another objective of dedollarisation is to foster economic autonomy. By reducing reliance on the dollar, countries gain greater control over their own monetary policies and financial systems. This is particularly crucial for nations concerned about potential US sanctions or other forms of economic pressure.

There are different approaches countries can take to dedollarise their economies. One approach is to decrease their holdings of the dollar. Another strategy involves increasing the use of their own currencies in international trade and investment. Some countries may encourage the adoption of alternative reserve currencies such as the euro or the yuan.

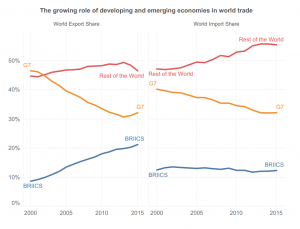

Several countries have already initiated measures towards dedollarisation. China has been actively promoting dedollarisation, utilising the yuan for trade in oil, coal, and metals with Russia. China has made agreements with 48 countries to use its currency in cross-border transactions, and the Yuan’s share in global transactions has risen to 7%. BRICS countries are also considering developing a common currency to compete with the dollar. Moscow and Beijing are leading the change toward dedollarisation. Iran has been trying to reduce its exposure to US sanctions by reducing the use of its own currency in international trade.

As dedollarisation of an economy will involve a complex network of exporters, importers, currency traders, debt issuers, and lenders, the process is still in its early stages. The US remains a most powerful economy, accounting for 11.5% of world trade and 24% of global GDP. While increased transactions in other currencies may make some progress in dedollarisation, the available evidence suggests that the dollar’s importance is likely to remain significant in the short term. However, this depends on whether the US restrains from further weaponisation of the dollar.

(The author is an economist based in Kochi. He was the head of the Departmentt of Economics, Central University of Kerala, Kasaragod.)

Dr Ravindran AM is an economist based in Kochi. He has more than three decades of academic and research experience with institutions such as CUSAT, Central University of Kerala, Cabinet Secretariat - New Delhi, and Directorate of Higher Education Pondicherry.