By Krishna Kumar Sinha

Indo-US trade relations: Kamala Harris’s ascendency to the vice-presidency of the United States mirrors the rise of Indian Americans as a successful ethnic group in the US. The recent trend of greater presence of Indian diaspora in the US public administration and corporates have given rise to the hope that this will result in better understanding between the two countries for all-round advancement of bilateral relations.

It was the reforms initiated in 1991 that heralded a major role of the US in India’s newly liberated economy in terms of increasing trade and foreign investment. The growing market, availability of IT-trained manpower and proficiency in English helped upscaling of the economic and trade ties between the two countries. In 2005, the relationship was enhanced to the level of strategic partnership during the presidency of George W. Bush, enlarging the field of cooperation to cover defence, nuclear energy, space, and high technology trade. The following 15 years witnessed increased high-level political visits at regular intervals and the beginning of wide-ranging dialogue across subjects of mutual interests, including those on economic and trade issues.

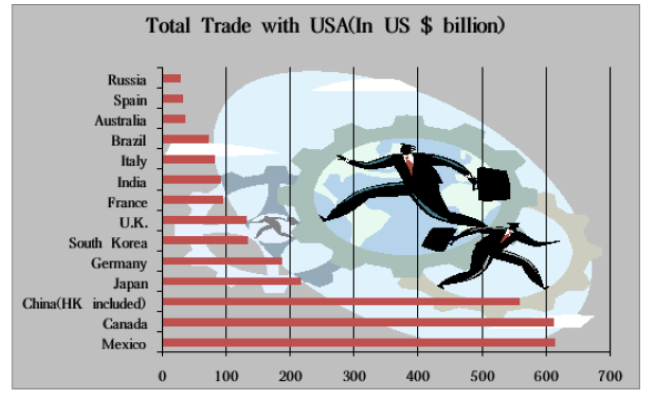

It was in this background that the two sides committed to work for increasing the annual bilateral trade in goods and services to $500 billion during the Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to the US in September 2014. The optimism on the bilateral trade front was backed by the 400% growth achieved during 2004-14 period to cross the milestone of $100 billion. However, six years later, the bilateral trade in goods and services is still around $146 billion which corresponds to a modest growth rate. Achieving the target of $500 billion trade does not seem an easy task even by 2025.

READ I PLI Scheme: Is the electronics industry’s window of opportunity closing?

Current status Indo-US trade and investment

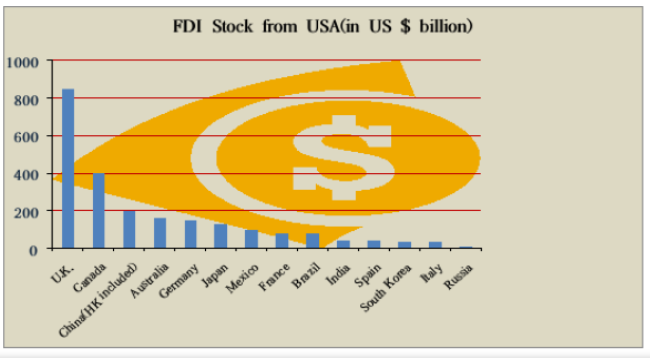

In 2019, the US became India’s largest trading partner. However, the total annual trade value with the US represents around 10% of our global trade and this has almost remained static since 2015-16. In terms of investment relations also, the US-based investors, the biggest source of capital and technology globally, have followed a limited and bit hesitant approach in the Indian equity market despite a much-touted large market, competitive labour and established rule of law in India.

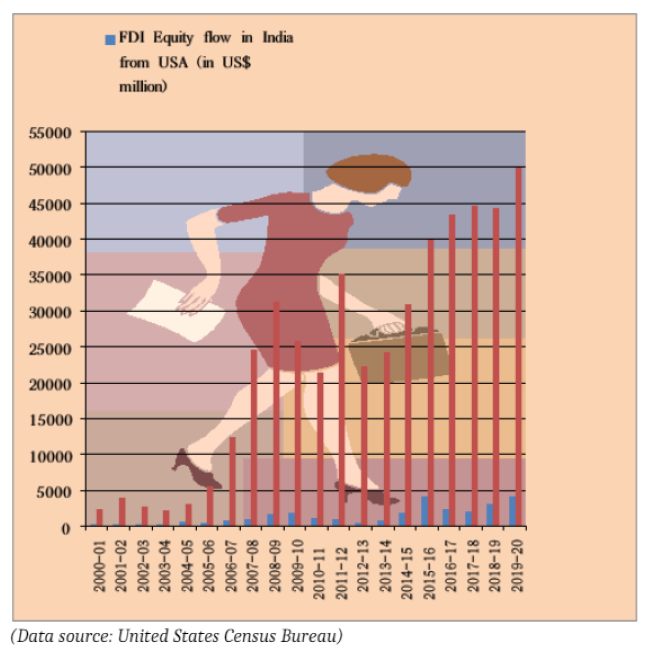

Analysing investment flow sector-wise from the US establishes the preference of US investors for the services sector. Manufacturing, especially greenfield investment in manufacturing activities, from the US is insubstantial. The annual inflow of FDI from the US has been in the range of $ 2-4 billion since 2015-16, though it is expected to be higher in 2020-21 with Facebook picking up a 9.99% stake in JioMart.

Globally, India is the fifth-largest economy on current prices basis and third largest on PPP terms. However, its trade and investment relations with the US, the biggest economy, do not justify the status as the graphs below depict.

FDI: A development tool

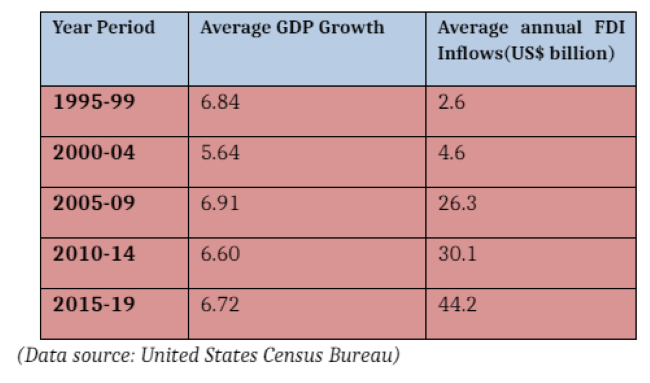

There is no consensus among researchers, analysts, and policymakers on the importance of FDI. All kinds of foreign investments are likely to be beneficial to the domestic economy. However, looking at the FDI inflows and GDP growth rates in the preceding 25 years in India gives credence to the idea that foreign investments help in sustaining growth over a long period.

India pulled 271 million people out of poverty during 2005-2015 period and the per capita income has seen an increase from $374 in 1995 to $2,100 in 2019. (source: https://www.macrotrends.net). The UNDP in its 2018 global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) report noted that the incidence of multidimensional poverty in India almost halved between 2005-06 and 2015-16 from 54.7% to 27.5%. The consequent emergence of the middle class with their spending habits helped India sustain growth. Thus, FDI’s role as a development tool appears credible.

A larger convergence of views has been observed concerning the direct benefits resulting from FDI in the manufacturing sector. This could be one of the reasons why many governments began to pursue policies towards attracting FDI in targeted sectors post 2000. The Narendra Modi government’s flagship programme Make in India and recently the introduced PLI scheme are seen as offshoots of this idea. The FDI induced technological advancements boost exporting capability of the manufactured products. Rising exports will create overall demand, helping economic growth, employment generation, and will reduce current account deficit. In the current global context, India stands to benefit since several American companies are inclined to relocating manufacturing base from China.

READ I Covid-19 vaccine diplomacy: India’s chance to deepen its strategic engagements

Trump’s economic nationalism

The America First policy of the Trump administration, implemented through ‘Buy American and Hire American’ order, is at the root of many federal decisions that created ripples in the world trade regime. Some of the decisions such as the imposition of 25 % duty on a range of imported steel products, inflicting additional duty of 25 % on $34 billion worth imports from China, designating China as a currency manipulator. The US President renegotiated and replaced NAFTA with a new agreement with Canada and Mexico, called the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) with a declared top priority of reduction in trade deficit. Most economists, however, believe that USMCA is unlikely to have a notable impact on US trade deficit, though it may help in job creation in the US.

In May 2019, President Trump ordered the termination of GSP eligibility of India based on market access issues. The decision has been questioned as the GSP programme enables many manufacturers in the US to source their intermediate goods at lower costs, making their final products more competitive. More than GSP benefits, it was President Trump’s verbosity and repeated mention of India as a “tariff king” that grabbed more media attention.

Indo-US trade and investment issues

During the final months of the tenure of President Trump, the officials of the two countries tried to negotiate a mini trade deal to address trade disputes related to market access. The primary US complaints stem from India’s use of tariff and non-tariff barriers to protect farmers and some manufacturing industries out of the fears that foreign competition would significantly disrupt livelihoods. Besides agriculture products, tariffs on information and communications technology products, price controls on coronary stents and knee-replacement hardware, and additional import duties on medical devices were also flagged by the US as other major areas of concern.

Although not much discussed in the public domain, the problems regarding Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) remain the most pressing bilateral trade issue between India and the US. The American business bodies have raised concerns regarding the restrictive patentability criteria under section 3(d) of the India’s Patent Act. On Copyright, the US side believes that to prevent high incidences of counterfeits in Indian physical and online markets, India should adopt effective measures to counter online piracy, consistent with international best practices. The Business Software Alliance (BSA) of the US has called for the strengthening of computer-related inventions as a patent-eligible subject matter under the Indian Patents Act.

The office of USTR annually prepares the Special 301 report which identifies countries that do not provide adequate IPR protection and fair market access to US entities. The report has classified India under the Priority Watch List in its 2019 edition of the Report clubbing with 35 other nations like Venezuela, Uzbekistan, etc.

India’s Compulsory Registration Order (CRO) regulations issued by the ministry of electronics and IT has also come under criticism of the US side describing it as counter-productive to the goal of Digital India as regulations increase manufacturing and compliance costs. Very recently, the US Congressional Research Service in its December 2020 Report highlighted investment barriers and restrictions on e-commerce platforms such as Amazon and Walmart-owned Flipkart under FDI policy.

India too has raised the anti-competitive practices of the US and pointed to Trump’s unilateral steel and aluminium tariffs and the use of anti-competitive subsidies for US domestic dairy producers as examples. India has repeatedly pressed for the finalisation of the US-India Social Security or Totalisation Agreement, to avoid double deductions from the income of employees working in each other’s countries, and allowing short-tenure Indian workers in the US to get back billions of dollars in social security deposits there.

According to an estimate, Indians working in the US forfeit almost $1 billion annually as social security tax. After several years of persuasion by India, the US Commerce department finally agreed in 2020 to discuss the matter as a bilateral issue. Frequent increases in H1B visa fees and procedural changes are cited as another key hindrance faced by Indian companies operating in the US.

Weighing at the scale of global trade disputes, the bilateral issues between India-US do not have the potential of becoming a major stumbling block in upscaling economic engagements. India should also realise that the US move to enhance tariffs on imports from China has created opportunities for other countries to become more competitive in the US market and countries like Mexico, Taiwan with robust manufacturing bases were benefitted immediately. India too benefitted in managing additional exports, though marginal, to the US. The government, aware of the possible gains, came out with the PLI scheme for a bigger share of the large market.

Although both sides have repeatedly emphasised that trade and investment constitute the core of the Indo-US strategic dialogue, the frequency of engagements to discuss these issues shows more focus on security-related issues. An early meeting between Indian commerce minister and his US counterpart, Katherine Tai, the United States Trade Representative (USTR) in the Biden administration, may help break the ice and reactivate several bilateral dialogue mechanisms established in the previous decade to discuss trade and investment issues. Unfortunately, during the Trump presidency, engagements were few and far between the two countries.

Indo-US trade in defence

The Doklam standoff with China followed by the clashes at Galwan Valley led to both India and the US acknowledging the Chinese threat. The consequent setting up of a 2+2 dialogue mechanism with the US along with QUAD joint military exercises represents a paradigm shift from India’s past policy. The signing of the Basic Exchange and Cooperation Agreement (BECA) during the third edition of the 2+2 dialogue between India and the US is another pointer to the strengthening of bilateral defence and military ties.

The framework of the ministerial level 2+2 dialogue was initiated in 2018 as part of the strategic partnership between the two countries and the two sides have met thrice in as many years. Earlier, in 2016, the US had designated India a Major Defence Partner and in the same year, they inked the Logistics Exchange Memorandum of Agreement (LEMOA). India and the US signed another pact called COMCASA (Communications Compatibility and Security Agreement) in 2018 that provides for interoperability between the two militaries and provides for the sale of high-end technology from the US to India.

India is now purchasing more for its defence use from US companies like C-17 Globemaster III for military transport, Boeing’s Chinook CH-47 as heavy-lift helicopters, Boeing’s Apache, and Lockheed Martin’s C-130J for airlifting troops. It was not a mere coincidence that the first visit by a senior US official after President Biden assumed office, was by Secretary of Defence General (Retd) Lloyd J. Austin.

Focus on trade, investment, technology

The diplomatic and military cooperation with the US could be a geopolitical necessity because of the increased Chinese economic and military threat, particularly in the Indo-pacific region. While it is good to see the US recognizing India’s role as a strategic partner, India needs to leverage its close partnership with the US to facilitate deeper integration into the global supply chain.

The effort for taking the relationship to the next level will require intensifying cooperation in areas such as higher education, university linkages, creating healthcare infrastructure and collaborative research in domains of green energy, advanced manufacturing, AI, 3-D printing. The following bilateral arrangements already established are considered good enough to sort out several irritants in the trade relationship and need to meet more frequently:

- Ministerial level Economic and Financial Partnership

- Ministerial level Trade Policy Forum

- India-U.S. CEO’s Forum

- The Strategic & Commercial Dialogue

- The Bilateral High Technology Cooperation Group

- Bilateral Investment Initiative, and U.S.-India Infrastructure Collaboration Platform

- The U.S.-India Energy Dialogue, replaced by the Strategic Energy Partnership

- The Higher Education Dialogue

- Indo-U.S. Science & Technology Joint Commission

- U.S.-India Health Dialogue

These aims and expectations of economic benefit with enhanced engagements with the world’s largest economy will require efforts from the government and corporate sector as well, and some suggested lines of actions are:

- Ensure regulatory and policy predictability, as part of efforts to further improve ease of doing business.

- Regular interactions between the two sides through established mechanisms with a focus on core issues affecting trade and investment.

- As business matters in the USA are more corporate-driven, the interaction between the corporate leaders of the two nations needs to be frequented through CEO Forum, etc.

- Flexible and practical approach to resolve identified impediments affecting cooperation at B2B level.

(Krishna Kumar Sinha is an industrial policy expert based in New Delhi. He retired from Indian Engineering Services in 2017. His last assignment with the government was as an Industrial adviser in the Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion, DIPP, currently known as DPIIT.)

Krishna Kumar Sinha is an industrial policy and FDI expert based in New Delhi. His last assignment was as an industrial adviser in the department of industrial policy and promotion, DIPP, currently known as DPIIT, under the ministry of commerce and industry of the government of India.