On September 27, 2020, the Union government introduced three farm laws, which were subsequently repealed on December 1, 2021 amid criticism from economists, farmer organisations, and political parties. Critics argued that these reforms, heralded without broad consultations or establishing general consensus, especially among farmers, lacked an adequate institutional framework and infrastructure for farmers to market their produce effectively.

Concerns arose within the agricultural community that these laws would dismantle the longstanding “mandis” (APMC markets) and threaten the minimum support price (MSP) system, pushing farmers into inequitable dealings with a handful of corporate entities and exposing them to exploitative practices.

The backlash highlighted the importance of institutional mechanisms to address the pervasive asymmetric information and corporate opportunism in the agricultural market. This was particularly pronounced in the context of the Farmers Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Act, 2020, known as the Contract Farming Act, 2020. Despite the potential benefits of contract farming, the lack of studies quantifying its downsides, such as opportunistic and asymmetric behavior, underscores a significant gap in understanding the true impact of these reforms on India’s agricultural landscape.

READ I Budget 2025 bets on infrastructure, fiscal prudence

Agricultural marketing reforms

Over the last two decades, India has seen concerted efforts to reform agricultural marketing. The Model APMC Act 2003 encouraged states to adopt reforms facilitating contract farming and private sales outside APMC yards. The introduction of the Model Contract Farming and Services Act, 2018 was aimed at streamlining agricultural marketing by reducing intermediaries and enhancing farmers’ income share. However, the three farm laws of September 2020, intended to further liberalise the sector, were withdrawn following extensive protests, highlighting the contentious nature of agricultural reforms in India.

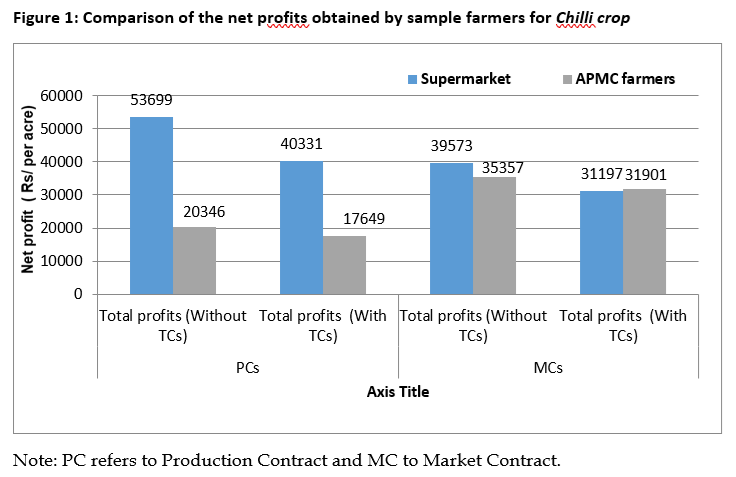

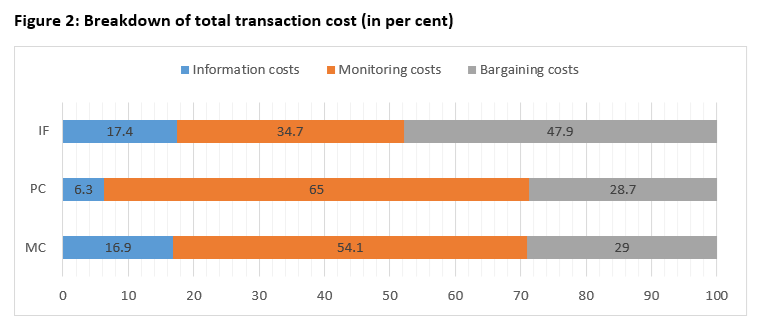

The protests against contract farming shed light on the increased transaction costs borne by farmers due to asymmetric information and opportunistic behavior by contracting firms. Our analysis categorises these costs into information, negotiation, and monitoring expenses, each contributing to the overall inefficiency and reduced profitability for farmers engaged in contract farming. This empirical examination, based on a field survey of 300 chilli farmers in Karnataka, reveals that while contract farming can offer higher profits compared to traditional APMC sales, the associated transaction costs significantly impact farmer earnings.

In the wake of the introduction of the three farm laws, concerns have been particularly pronounced among small and marginal farmers who represent a significant segment of India’s agricultural sector. The apprehension that these reforms would disproportionately benefit larger agricultural entities at the expense of smaller ones has been a focal point of the debate.

Smallholders feared that the dismantling of traditional safety nets such as the MSP and APMC markets would leave them vulnerable to market volatilities and diminish their bargaining power against large corporations. This demographic’s unique challenges highlight the critical need for agricultural reforms to be both inclusive and attuned to the diverse realities of the farming community in India. Addressing these concerns requires a nuanced approach that safeguards the interests of small and marginal farmers, ensuring that reforms do not exacerbate existing inequalities within the agricultural sector.

Furthermore, the environmental implications of the shift towards large-scale contract farming, as encouraged by the farm laws, warrant careful consideration. Critics have voiced concerns that such reforms may promote practices conducive to monoculture and high-input agriculture, potentially undermining the sustainability of farming practices.

The emphasis on efficiency and scalability, though beneficial from an economic standpoint, risks marginalising environmentally sustainable farming methods traditionally practiced by smaller farmers. This tension between economic objectives and environmental sustainability poses a crucial question: how can future reforms strike an optimal balance between enhancing agricultural productivity and preserving the ecological integrity of farming practices? The answer lies in crafting policies that not only incentivise efficiency but also support and promote the adoption of eco-friendly farming techniques across all scales of agricultural operations.

Addressing the shortcomings

The Model Contract Farming and Services Act, 2018, and the subsequent Farmers Agreement Act, fall short in addressing the inherent market imperfections and fail to establish mechanisms to mitigate the opportunistic behavior of contracting firms and the information asymmetry between them and the farmers. These laws overlooked the need for a robust framework to ensure fair procurement practices and equitable bargaining power for farmers.

To overcome these challenges, institutional mechanisms need to be strengthened to ensure clear, enforceable contracts, and curb the exploitative practices of contracting firms. Empowering farmer collectives and improving market knowledge can mitigate price uncertainties and enhance product quality standards. Encouraging formal contracts with farmer producer organisations (FPOs) and investing in rural market infrastructure are critical steps towards creating a competitive and fair agricultural market.

The withdrawal of the three farm laws and the controversies surrounding contract farming underscore the complexity of the country’s agriculture sector. A thoughtful approach, prioritising farmer welfare and informed by empirical evidence, is essential for any future reforms. Engaging farmers in the reform process and investing in the farming infrastructure will be key to achieving sustainable and inclusive growth in India’s agricultural sector.

(Dr Kedar Vishnu is Assistant Professor of Economics at Narsee Monjee Institute of Management Studies, Mumbai. Prof. Parmod Kumar is Director of the Giri Institute of Development Studies, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh.)