By Abhijit Roy

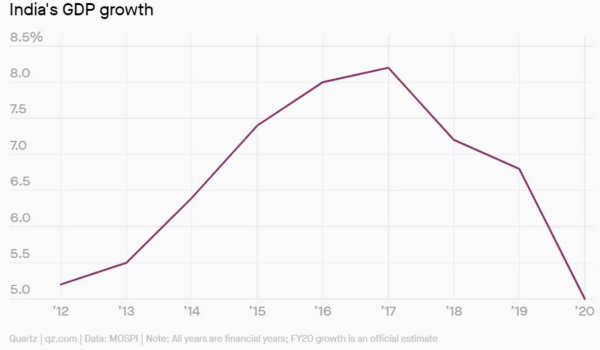

India’s middle class has been shrinking and Covid-19 has crushed it. A few years ago, our presentations used to show a rosy picture of India having a 200 to 300 million middle class population with growing incomes and global aspirations. This created a boom in real estate, automobile, retail, travel and tourism, and education. The GDP growth was powered largely by the demand generated by this middle class, middle income growth — an exploding consumer market that McKinsey Global Institute in 2007 described as India’s “bird of gold”.

The reality check actually began last year when a noted government economist sounded the first alarm that India is facing a middle-income trap. What it means is that middle class incomes reach a point of growth and then stalls there, refusing to move up any further and even declining. New data began to emerge that the middle class is actually around 150 million, half of what was being painted earlier. Actually, the size of the middle class is now anyone’s guess.

READ I India’s storied middle class may be sliding into poverty

India’s economy was slowing since 2016 when we pulled the handbrakes suddenly. Depending on the measures used, the estimated size of this middle-class ranges between 78 million (Economist, Jan 2018) to 604 million (Krishnan and Hatekar, EPW June 2017). Actually, the size of the middle class depends on the income yardstick one applies to define it.

Economists have used an income threshold that defines middle class people as those living on between $2 to $10 per person per day, valued at 1993 purchasing power parity (PPP) dollars. (Purchasing power parity enables you to compare how much you can buy for your money in different countries.) So, you can very well gauge the wide disparities in the range of population that falls under middle class. Then there is urban middle class and rural middle class where there is a difference in purchasing power.

If you consider the urban middle class, then it is mostly the salaried class (you can split hairs on this). This segment has been pummelled in the last few years. They have lost jobs, seen their real estate investments plummet, investment incomes shrink from continuously declining bank interests, and volatile capital markets erode their wealth. Covid19 has dealt the deadliest blow to this sector.

Now it was the demand side of the economy that was pushing up the GDP and holding aloft India’s global ambitions. While the government is rightly concerned about the agriculture sector (one hopes that this concern is genuine), those who are extremely poor and the manufacturing verticals to shore up the economy, precious little has been done for the middle class which has been the bulwark of the economy.

READ I Middle-class distress biggest challenge for Nirmala Sitharaman

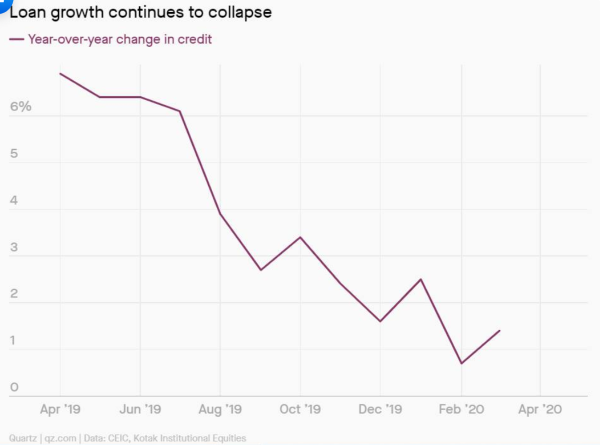

Recent policies have largely been towards reducing interest rates to help businesses get cheaper loans to increase their production. This is supply side economics at work, missing out the demand side. Now, why would manufacturers borrow more if demand isn’t there? They already have 50% idle capacity because demand has fallen. So, there are few takers for low-interest bank loans. Let’s check the data, the credit growth in the country fell from 6.9% in April 2019 to a meagre 1.4% in March 2020. Obviously, policy decisions to cut interest rates haven’t worked. People will go to the malls to feel good, but they will spend only on small feel-good purchases.

India is caught in a peculiar situation, businesses are not borrowing because they face a demand recession, the middle class is now borrowing because they can’t afford to pay off mortgages as their incomes have shrunk. This is the reality of India’s economy. It’s aspirations to become a $5 trillion economy lies in tatters, it cannot have a domestic demand-led growth because it has a shrunk and impoverished the middle class. If one doesn’t understand this basic problem, and takes care to define it, the solution will never happen. It just needs common sense, which is absent in the government thinking, to understand the core of the problem. It needs talent to work out solutions, but the best brains have left the administration.

(Abhijit Roy is a technology explainer and storyteller. He spent more than 20 years in the IT industry after starting his career as a journalist. The views are personal.)