India, the world’s largest producer and exporter of rice, contributes almost 40% to global demand. However, it faces the complex challenge of balancing domestic food security with the benefits of international trade. Factors like the El-Nino effects, uneven monsoons, and external challenges such as supply chain disruptions, financial and logistical blockages, and the fallout of the Russia-Ukraine conflict have exacerbated these challenges. In response, the government has implemented a complex export policy regime using instruments such as export licensing, state trading, minimum export pricing, and export duties.

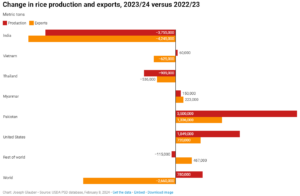

Rice export restrictions have ensured reasonable domestic supplies and controlled inflation amid sub-optimal production of other staples like wheat and maize, benefiting consumers. However, these restrictions have also negatively impacted India’s agricultural exports, further stressing the already struggling rural economy and rice producers.

Understanding the reasons, rationale, and way forward for India’s rice sector is paramount. Discussions led by Shri Amit Shah with industry stakeholders aim to address these issues by finding a balance between sustaining domestic supply and leveraging international trade opportunities. This text explores the systemic challenges to India’s rice sector and discusses the way forward.

READ I India-ASEAN FTA: India seeks to revisit single tariff schedule

Reasons for rice export curbs

India’s rice export policies are a strategic blend of economic considerations and domestic food security needs, varying significantly across different types of rice. For Basmati rice (HSN ‘10063020’), exports are free with a minimum price of $1,200 per ton. This ensures India earns significant foreign exchange while maintaining the premium quality and market positioning of Basmati rice. The price floor prevents undervaluation, dumping, and ill-positioned firm-level undercutting and competition.

Additionally, parboiled rice (HSN ‘10063010’) and brown rice (HSN ‘10062000’) are also freely exportable but with a 20% duty, balancing the need to support farmers and exporters while ensuring domestic availability. This duty generates revenue and manages export volume, ensuring sufficient domestic supply given the health benefits of brown rice and its growing popularity among the local populace.

Non-basmati white rice (HSN ‘10063090’) is prohibited from export to stabilise local markets and prevent shortages or price increases that could impact low-income households. Furthermore, broken rice (HSN ‘10064000’) export is generally prohibited but allowed with government permission to address the food security needs of other countries, reflecting India’s role in global humanitarian efforts while safeguarding domestic needs. Husked paddy (HSN ‘10061090’) also faces export restrictions, ensuring that value addition from milling occurs domestically, benefiting local producers and generating additional economic activities and employment.

These varied policies reflect India’s careful approach to managing its rice exports, aiming to balance generating export revenue with maintaining domestic food security and economic stability. The restrictions on non-Basmati white rice and broken rice underscore the importance of ensuring that staple varieties remain available for domestic consumption, particularly for low-income populations. In contrast, the regulated free export of premium and parboiled varieties illustrates a strategy to maximise foreign exchange earnings while protecting local markets from potential adverse impacts.

Sustainable policy framework

India’s export policies for rice are complex, aiming to balance the needs of consumers and producers. These policies often strain farm incomes, exacerbating challenges in rural economies and weakening demand for white goods, consumables, and non-essential items. Rice is a crucial calorie source for half the global population and a staple for the poorest in Asia and Africa. To balance this, we need a transparent, sustainable, and inclusive policy regime for the agricultural sector.

Given the uneven rainfall resulting in large-scale floods as well as severe rain deficits in certain parts of the country, the government of India may exercise caution in any prompt decision on rice export policies. However, given the record plantation of paddy across the country and the smooth operationalisation of the Black Sea Grain Corridor, supply chain disruptions are likely to ease. Furthermore, India is likely to witness a record rice production of 133-138 MT in 2024-25, giving the government scope to revisit rice export policies with certain caveats.

For example, a minimum export price of $1,200 for Basmati rice and a flat duty of $100 for non-Basmati rice, including white rice, parboiled, husked paddy, and brown rice, would simplify the policy framework and bring fairness and transparency to India’s export policy regime. This approach would ensure fair pricing while preventing market distortions and undervaluation.

Moreover, value-added rice products should remain freely traded. This includes rice bran and oil, flour, syrup, cakes, milk, starch, protein, vitamin concentrates, pasta, crisps, snacks, rice kernels, pet food, wine, vinegar, noodles, crackers, pudding, and rice cereal. In this context, the recent export ban on rice bran oil and some other value-added products was illogical. Promoting the export of these value-added products can enhance economic activities, generate employment, and increase foreign exchange earnings.

Additionally, a policy revisit is needed in the context of allegations by countries such as Australia, Brazil, Canada, Switzerland, and the UK at the WTO for ensuring unrestricted tendering and supplies to the UN World Food Program and associated obligations under other international agreements, especially for white non-Basmati rice.

Value-added exports

India’s rice export policies should foster an ecosystem for value-added products with the right segmentation, targeting, and positioning. For instance, while Europeans have grown fond of Basmati rice, broken rice is in high demand in Western African countries due to their low per capita income.

Indian rice exporting firms should scan the right segments and accordingly target and position their products. For example, South Europeans favor sticky, wet rice for dishes like risotto and paella, while North Europeans prefer dry-cooked rice. Additionally, North European consumers are increasingly interested in specialty rice varieties like waxy, jasmine, wild, and colored rice, and such niche export opportunities should be scaled by Indian firms.

By capitalising on these opportunities at both the policy and operational levels and proactively addressing the associated challenges, the Indian rice sector can ensure its continued growth and contribute sustainably to the nation’s economic development. This approach balances domestic needs with international market demands, promoting resilience and prosperity in the agricultural sector. Lastly, we must remain a committed, transparent, and reliable supplier of global public goods in sync with agreed international norms and associated obligations.

Ram Singh is Professor & Head, and Aaqib Chaudhary is Research Scholar at IIFT, New Delhi.