A universal pension scheme for India: In old age, people generally become less productive financially and are unable to earn sufficiently to take care of themselves. India’s share of elderly people, those above 60 years of age, is estimated to be 11% (15.9 crore) in 2024 and projected to be 20% (34.8 crore) by 2050. Currently, only 27-30% of the elderly receive financial support through pensions. This includes pensioners of Union, state, and local governments, the Employees’ Pension Scheme, the Indira Gandhi National Old Age Pension Scheme (IGNOAPS), and other occupational private pensions. Thus, India is characterised by low pension coverage for the elderly, with IGNOAPS remaining the only social pension funded by the government, covering 18.5% of the elderly.

Since 1995, in accordance with Article 41 of the Indian Constitution and following the Directive Principles of State Policy, the Union government’s ministry of rural development introduced pension benefits for destitutes, starting at Rs 75 for those 65 years and above. In 2007, the IGNOAPS amount was revised to Rs 200 for all citizens below the poverty line (BPL). In 2011, the qualifying age for the pension was reduced to 60. Additionally, BPL elderly aged 80 or above were entitled to Rs 500. Currently, a flat universal pension, means-tested by income, residence, and age, is available to all Indians.

READ I Karnataka bill for job quotas can open up a can of worms

Towards a universal pension scheme

Since 2009, government pension schemes such as the National Pension System (May 1, 2009) and Atal Pension Yojana (May 9, 2015) have been available. Tailored pension schemes targeting economically disadvantaged sections, like the National Pension Scheme Lite (April 1, 2010) and Pradhan Mantri Shram Yogi Maandhan Yojana (February 1, 2019), have also been introduced. However, these schemes require systematic long-term contributions, which poses a challenge to their sustainability as people are often short-sighted about future savings.

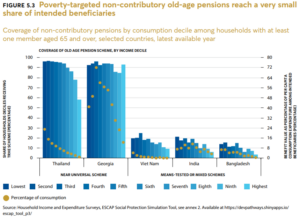

Pensions, along with smoothing consumption and mitigating longevity risks, also reduce income inequality and poverty through intra- and intergenerational transfer of resources. Therefore, to promote the welfare of the elderly, a universal pension scheme, means-tested only by age and residence, is recommended. This approach provides higher coverage and lowers administrative costs.

International experience demonstrates that over 80 developing countries have introduced social security pensions. Among them, several countries provide a pension to the elderly with no test other than residence and age, including Bolivia, Botswana, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Guyana, Kosovo, Lesotho, Mexico, Mauritius, Nepal, Namibia, New Zealand, Samoa, Suriname, and Zanzibar.

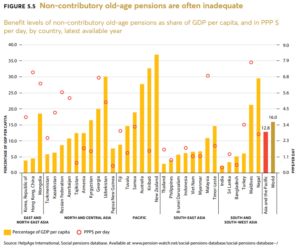

The financial burden of offering a universal pension scheme is not large. For instance, a monthly pension of Rs. 1000 to 15.9 crore senior citizens would amount to Rs. 1.9 lakh crore in 2024-25, or nearly 0.6 percent of GDP. Most countries finance their universal social pension scheme (USPS) through general taxation. Several developing countries, due to the informal nature of their economies, fund pensions through consumption taxes, corporate taxes, special taxes on luxury goods and “bad goods,” and CSR funds. Lesotho and Swaziland fund their universal social pension schemes out of general taxation, while Costa Rica uses a blend of payroll, sales, and cigarette taxes.

In India, USPS can be funded through a marginal increase in taxes on income and profits (by enhancing cess), certain luxury goods and services, “bads” (alcohol and cigarettes), and trading profits. Implementing a universal pension scheme for the elderly would increase pension coverage by 70 percent (104 million). The Periodic Labour Force Survey (2019-20) shows that 90 percent of wage earners earn less than Rs. 25,000, implying that workers have little to save for the future. USPS would act as a savior not only for the elderly but for future generations, upholding social equity and welfare.

The probability of the elderly using pension funds for the welfare of the family is higher than that of the younger generation. The elderly are generally considered more responsible and can supplement family resources in a more meaningful way. This would also reward the elderly who have served the country in their youth, allowing them to retire with a degree of personal comfort, free from worry, and with dignity.

Dr Charan Sigh is a Delhi-based economist. He is the chief executive of EGROW Foundation, a Noida-based think tank, and former Non Executive Chairman of Punjab & Sind Bank. He has served as RBI Chair professor at the Indian Institute of Management, Bangalore.